Course Description

I realize that “Modes of Assertion” is a rather cryptic title for the course. What we will explore are ways of modulating the force of an assertion. This will engage us in formal semantics and pragmatics, the theory of speech acts and performative utterances, and quite a bit of empirical work on a …

I realize that “Modes of Assertion” is a rather cryptic title for the course. What we will explore are ways of modulating the force of an assertion. This will engage us in formal semantics and pragmatics, the theory of speech acts and performative utterances, and quite a bit of empirical work on a not-too-well understood complex of data.

“He obviously made a big mistake.”

“It is obvious that he made a big mistake.”

If you’re like me you didn’t feel much of a difference. But now see what happens when you embed the two sentences:

“We have to fire him, because he obviously made a big mistake.”

“We have to fire him, because it is obvious that he made a big mistake.”

One of the two examples is unremarkable, the other suggests that the reason he needs to be fired is not that he made a big mistake but the fact that it is obvious that he did.

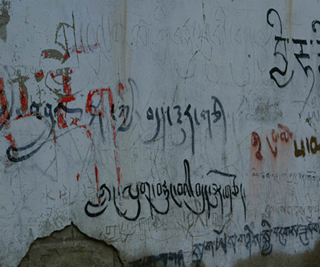

We will try to understand what is going on here and look at related constructions not just in English but also German (with its famous discourse particles like ja) and Quechua and Tibetan (with their systems of evidentiality-marking, as recently studied in dissertations from Stanford and UCLA).

Course Info

Instructor

Departments

Topics

Learning Resource Types