Culture

The West's Biggest Export?

Alex Donaldson

I spent a month over the summer of

2002 trekking in Borneo with a team of 15 other boys from my school. This

was the first time that I had traveled outside England, my home, to a

destination that was not geared towards hosting tourists. The expedition

provided me with a very interesting perspective on the march of developed

culture across the globe. The tourism industry is simply one example of

this expansion, but it is an interesting example because it is the

industry that takes the public to these “exotic” lands.

The 20th century has seen the

creation and rapid expansion of the tourism industry, fuelled by our

ability to travel faster and more conveniently to remote places on the

planet. Tourism describes a huge variety of different activities, all

falling under the banner of people traveling for pleasure. I think of

tourists as falling into two main categories, those people who travel to

find somewhere to relax, and those who travel to experience new cultures.

The first category has less direct effect on the spread of tourism, as

these people prefer to travel to places in developed countries, where they

can relax in comfort. The second category likes to travel to experience

new cultures and environments without necessarily having a relaxing trip.

It is these people who are constantly pushing the tourist industry into

new areas. Once the tourist industry realizes a region is becoming popular

with adventurous tourists, big resort hotels appear, and the wild is tamed

for the benefit of the tourist who likes to feel adventurous without

having to endure the hardship of dingy, cockroach-ridden hotels. The

location is now ruined for the adventurous tourist. These westernized

resorts can be found all over the world, giving a highly sanitized version

of the local culture. This leaves the adventurers to go in search of a new

location to visit, an even more remote and exotic place is visited, and so

the cycle continues until we will have a resort hotel next to every lake,

mountain, forest and beach on the planet.

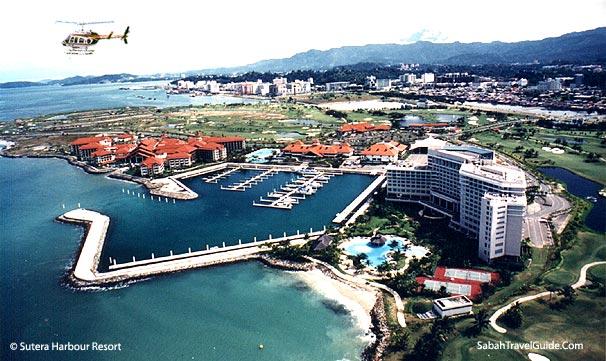

I have been lucky enough to see

this expansion of tourism firsthand during my trip to Malaysian Borneo in

the summer of 2002.  This was a very interesting place to visit because

different parts of the country are at different points in the transition

between untouched wilderness and popular tourist spots. The place I

visited where this transition was furthest developed was the city of Kota

Kinabalu in the north of Borneo. I knew from the start that this town was

different from the others I had visited further to the South. The airport

was fully enclosed and airconditioned, with numerous gift shops; all of

this was clearly designed with the foreign traveler in mind (Malays find

air-conditioning too cold after living in the tropics all their lives). We

made a couple of day trips to one of the numerous little islands a

30-minute boat ride from Kota Kinabalu. This island could only be

described as paradise; pine trees shaded the beach from the blazing

equatorial sun. Ten meters out in the deep blue sea there was a coral reef

buzzing with life, and best of all there were only 50 people on the island

at most and this was at the height of the tourist season. I cannot see the

situation staying like this for long though; several large hotels already

dominate the sea front of Kota Kinabalu. We had to pay to get onto the

island, and there were Pizza Huts and MacDonalds scattered around the

town. Yet we still stood out as tourists; seeing other white people was

rare, because Kota Kinabalu is not an international tourist destination.

All it would take would be one well-placed newspaper or magazine article

and it could become a very popular destination.

This was a very interesting place to visit because

different parts of the country are at different points in the transition

between untouched wilderness and popular tourist spots. The place I

visited where this transition was furthest developed was the city of Kota

Kinabalu in the north of Borneo. I knew from the start that this town was

different from the others I had visited further to the South. The airport

was fully enclosed and airconditioned, with numerous gift shops; all of

this was clearly designed with the foreign traveler in mind (Malays find

air-conditioning too cold after living in the tropics all their lives). We

made a couple of day trips to one of the numerous little islands a

30-minute boat ride from Kota Kinabalu. This island could only be

described as paradise; pine trees shaded the beach from the blazing

equatorial sun. Ten meters out in the deep blue sea there was a coral reef

buzzing with life, and best of all there were only 50 people on the island

at most and this was at the height of the tourist season. I cannot see the

situation staying like this for long though; several large hotels already

dominate the sea front of Kota Kinabalu. We had to pay to get onto the

island, and there were Pizza Huts and MacDonalds scattered around the

town. Yet we still stood out as tourists; seeing other white people was

rare, because Kota Kinabalu is not an international tourist destination.

All it would take would be one well-placed newspaper or magazine article

and it could become a very popular destination.

Another town that I visited was

just starting on the road to becoming a tourist location. Bario is a small

(pop ~500) rice-growing town, accessible only by air. The only foreigners

to visit were student groups (like my team) or people with a professional

interest in the area.  There was no infrastructure to support any other

kind of visitor. My team had the privilege staying in one of the village

longhouses; these are literally long wooden structures housing several

family groups. The accommodation was definitely not luxurious, but for

backpackers it provided a place to stay where we could immerse ourselves

in the culture. For a week we lived under the same roof with 10 village

families, and we ate their rice and wild boar crouched around one of the

few electric lights. We worked alongside the locals repairing the

irrigation system for their paddy fields. On our final night in the

village we even took part in a traditional ceremony and dance, performed

for us for the work we did for the village. This is what some tourists

want from traveling, so there is definitely the potential for Bario to

support a tourism industry even if it is only a few rooms for rent. Our

local hosts recognized this and were very interested to hear how we felt

while staying in the village. They were very eager to learn how to make

the longhouse a more comfortable environment for travelers. We had some

trouble convincing them that they had provided the most enjoyable

accommodation on the trip; in fact it was a place many of us will never

forget. By the end of our stay there was talk of our team leader returning

to Bario to help the longhouse establish itself as a place for people to

stay, hopefully without loosing the genuine feel we experienced while

staying there. It will be many decades before Bario develops even a small

tourism industry, but it is only a matter of time. Fifty years ago no

group of students would have been able to delve so deeply into Bornean

culture, yet now it is seen as common thing for youths to do (at least in

Britain) as part of a wider education about the world. Fifty years from

now those boundaries will be pushed even further back, to the point where

they may even disappear entirely.

There was no infrastructure to support any other

kind of visitor. My team had the privilege staying in one of the village

longhouses; these are literally long wooden structures housing several

family groups. The accommodation was definitely not luxurious, but for

backpackers it provided a place to stay where we could immerse ourselves

in the culture. For a week we lived under the same roof with 10 village

families, and we ate their rice and wild boar crouched around one of the

few electric lights. We worked alongside the locals repairing the

irrigation system for their paddy fields. On our final night in the

village we even took part in a traditional ceremony and dance, performed

for us for the work we did for the village. This is what some tourists

want from traveling, so there is definitely the potential for Bario to

support a tourism industry even if it is only a few rooms for rent. Our

local hosts recognized this and were very interested to hear how we felt

while staying in the village. They were very eager to learn how to make

the longhouse a more comfortable environment for travelers. We had some

trouble convincing them that they had provided the most enjoyable

accommodation on the trip; in fact it was a place many of us will never

forget. By the end of our stay there was talk of our team leader returning

to Bario to help the longhouse establish itself as a place for people to

stay, hopefully without loosing the genuine feel we experienced while

staying there. It will be many decades before Bario develops even a small

tourism industry, but it is only a matter of time. Fifty years ago no

group of students would have been able to delve so deeply into Bornean

culture, yet now it is seen as common thing for youths to do (at least in

Britain) as part of a wider education about the world. Fifty years from

now those boundaries will be pushed even further back, to the point where

they may even disappear entirely.

As the developed countries, like

Japan and America reach out into more and more remote locations it can

dilute and westernize the local cultures, as I experienced firsthand in

Malaysia. Before the trip I received many warnings about the culture shock

that I would go through on arrival in country, but in reality that concern

was misplaced. Everybody had mobile phones and went around wearing

football (soccer) shirts, and the malls were filled with bootlegged copies

of all the latest Hollywood and Bollywood movies. Even all the way out in

Bario the locals rode around on mopeds; it was quite a sight to see a

village Elder bumping down a dusty track, elongated earlobes flapping in

the breeze. I could also still buy my Mars bars and Coke at one of the

local shops, albeit at twice the normal price. This is not to say the

culture was not different, but there were some very strong western themes

running through it. I found this slightly disturbing, that a country

should forsake its own roots to copy the developed nations. This was

clearly what was happening, because alongside the western cultural ideas

there were also strong Japanese links, such as Japanese MTV on all the

local televisions. The Japanese connection makes more sense considering

the closer geographical and cultural proximity of the two countries. But

every time we met a local the conversation quickly strayed to discussion

of English soccer teams. This is all very bad news for global cultural

diversity; it looks like we are heading to a world filled with different

flavors of Western culture, a product of the huge increases in global

travel. The majority of people who travel for business or pleasure feel

more comfortable not having to deal with a completely different culture.

In its efforts to be accepted globally maybe Malaysia is doing the right

thing to make westerners feel more at home, but only at the expense of its

own individuality. Malaysia has even set a time frame for its progress as

a world player; the government has declared that the country wishes to be

“developed” by 2020. Exactly how they define this I am not sure, but the

impression I got from living in the country for a month was that

“developed” meant, simply, like America.

Does this mean that the

backpacker’s days are numbered? Maybe, but I believe it will be a long

time before Western culture completely dominates the globe. There will

still be places for us to explore and new cultures to experience for a

long time yet. Of course these places will be more and more remote, but

that only adds to the challenge. My experience in Malaysia may paint a

gloomier picture than is representative of the overall situation. Malaysia

is a long way down the road to becoming a developed nation; there are

plenty of other countries in the world in far worse situations than it is.

These places still have a chance to preserve their individuality. I cannot

help but ask myself, am I being selfish? Should these countries be

striving to preserve their individuality? To do so is to swerve away from

the conventionally accepted path to development. The question this poses

is, is the American way the only path to development? I find this a very

difficult question to answer. Japan does seem to have managed to become a

world leader, while still maintaining strong links with its heritage. I

believe this occurred simply because the two cultures grew side by side;

Japan had an established “developed” culture by the time American culture

really started to sweep the globe. These were the first global cultures to

emerge, which is why everyone else is now following them. The rest of the

world will always be following them though; these countries simply have

too great a head start. Only by finding their own unique brand of

development will places like Borneo really succeed. I do therefore believe

that the wish to preserve the individuality of a developing country is

very important and not entirely selfish. I hope that the developing

countries wake up and realize this before it is too late.