Reading 22: Queues and Message-Passing

Software in 6.005

| Safe from bugs | Easy to understand | Ready for change |

|---|---|---|

| Correct today and correct in the unknown future. | Communicating clearly with future programmers, including future you. | Designed to accommodate change without rewriting. |

Objectives

After reading the notes and examining the code for this class, you should be able to use message passing (with synchronous queues) instead of shared memory for communication between threads.

Two models for concurrency

In our introduction to concurrency, we saw two models for concurrent programming : shared memory and message passing .

-

In the shared memory model, concurrent modules interact by reading and writing shared mutable objects in memory. Creating multiple threads inside a single Java process is our primary example of shared-memory concurrency.

-

In the message passing model, concurrent modules interact by sending immutable messages to one another over a communication channel. We’ve had one example of message passing so far: the client/server pattern , in which clients and servers are concurrent processes, often on different machines, and the communication channel is a network socket .

The message passing model has several advantages over the shared memory model, which boil down to greater safety from bugs. In message-passing, concurrent modules interact explicitly , by passing messages through the communication channel, rather than implicitly through mutation of shared data. The implicit interaction of shared memory can too easily lead to inadvertent interaction, sharing and manipulating data in parts of the program that don’t know they’re concurrent and aren’t cooperating properly in the thread safety strategy. Message passing also shares only immutable objects (the messages) between modules, whereas shared memory requires sharing mutable objects, which we have already seen can be a source of bugs .

We’ll discuss in this reading how to implement message passing within a single process, as opposed to between processes over the network. We’ll use blocking queues (an existing threadsafe type) to implement message passing between threads within a process.

Message passing with threads

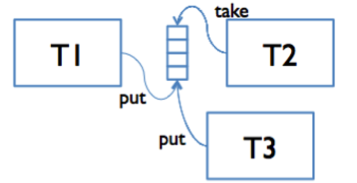

We’ve previously talked about message passing between processes: clients and servers communicating over network sockets . We can also use message passing between threads within the same process, and this design is often preferable to a shared memory design with locks, which we’ll talk about in the next reading.

Use a synchronized queue for message passing between threads.

The queue serves the same function as the buffered network communication channel in client/server message passing.

Java provides the

BlockingQueue

interface for queues with blocking operations:

In an ordinary

Queue

:

-

add(e)adds elementeto the end of the queue. -

remove()removes and returns the element at the head of the queue, or throws an exception if the queue is empty.

A

BlockingQueue

extends this interface:

additionally supports operations that wait for the queue to become non-empty when retrieving an element, and wait for space to become available in the queue when storing an element.

-

put(e)blocks until it can add elementeto the end of the queue (if the queue does not have a size bound,putwill not block). -

take()blocks until it can remove and return the element at the head of the queue, waiting until the queue is non-empty.

When you are using a

BlockingQueue

for message passing between threads, make sure to use the

put()

and

take()

operations, not

.

add()

and

remove()

Analogous to the client/server pattern for message passing over a network is the producer-consumer design pattern for message passing between threads. Producer threads and consumer threads share a synchronized queue. Producers put data or requests onto the queue, and consumers remove and process them. One or more producers and one or more consumers might all be adding and removing items from the same queue. This queue must be safe for concurrency.

Java provides two implementations of

BlockingQueue

:

-

ArrayBlockingQueueis a fixed-size queue that uses an array representation.putting a new item on the queue will block if the queue is full. -

LinkedBlockingQueueis a growable queue using a linked-list representation. If no maximum capacity is specified, the queue will never fill up, soputwill never block.

Unlike the streams of bytes sent and received by sockets, these synchronized queues (like normal collections classes in Java) can hold objects of an arbitrary type. Instead of designing a wire protocol, we must choose or design a type for messages in the queue. It must be an immutable type. And just as we did with operations on a threadsafe ADT or messages in a wire protocol, we must design our messages here to prevent race conditions and enable clients to perform the atomic operations they need.

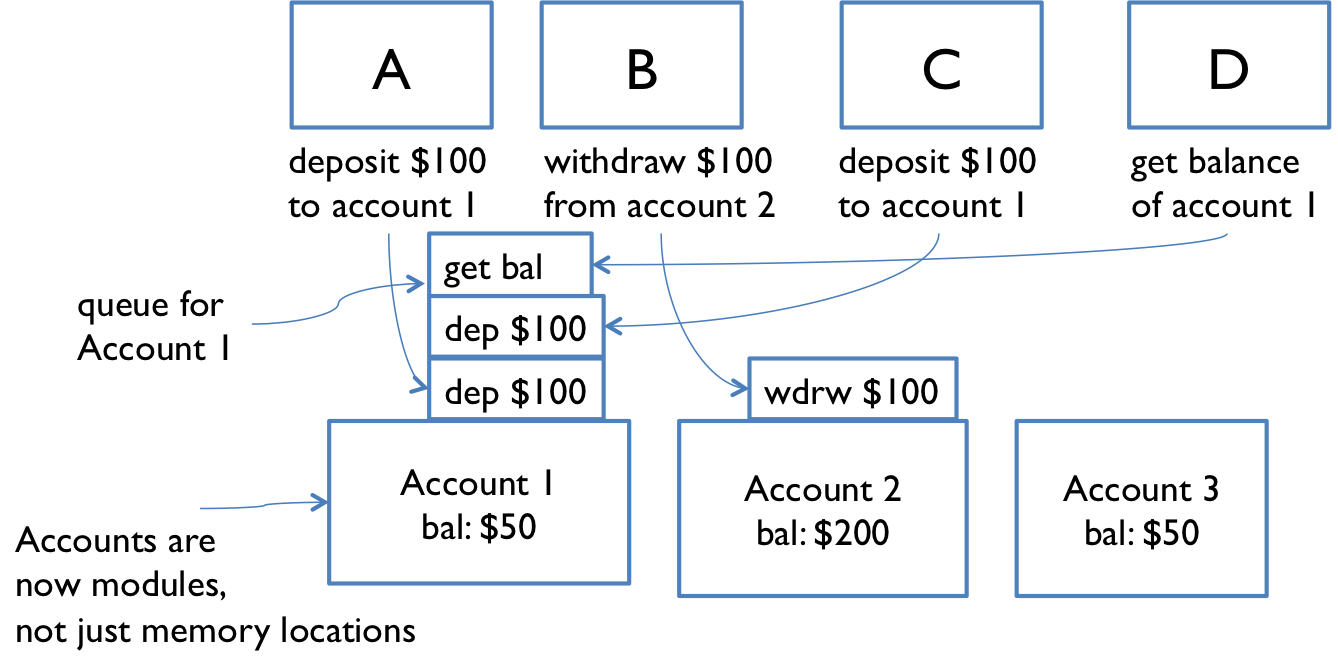

Bank account example

Our first example of message passing was the bank account example .

Each cash machine and each account is its own module, and modules interact by sending messages to one another. Incoming messages arrive on a queue.

We designed messages for

get-balance

and

withdraw

, and said that each cash machine checks the account balance before withdrawing to prevent overdrafts:

get-balance

if balance >= 1 then withdraw 1But it is still possible to interleave messages from two cash machines so they are both fooled into thinking they can safely withdraw the last dollar from an account with only $1 in it.

We need to choose a better atomic operation:

withdraw-if-sufficient-funds

would be a better operation than just

withdraw

.

Implementing message passing with queues

You can see all the code for this example on GitHub: squarer example . All the relevant parts are excerpted below.

Here’s a message passing module for squaring integers:

/** Squares integers. */

public class Squarer {

private final BlockingQueue<Integer> in;

private final BlockingQueue<SquareResult> out;

// Rep invariant: in, out != null

/** Make a new squarer.

* @param requests queue to receive requests from

* @param replies queue to send replies to */

public Squarer(BlockingQueue<Integer> requests,

BlockingQueue<SquareResult> replies) {

this.in = requests;

this.out = replies;

}

/** Start handling squaring requests. */

public void start() {

new Thread(new Runnable() {

public void run() {

while (true) {

// TODO: we may want a way to stop the thread

try {

// block until a request arrives

int x = in.take();

// compute the answer and send it back

int y = x * x;

out.put(new SquareResult(x, y));

} catch (InterruptedException ie) {

ie.printStackTrace();

}

}

}

}).start();

}

}

Incoming messages to the

Squarer

are integers; the squarer knows that its job is to square those numbers, so no further details are required.

Outgoing messages are instances of

SquareResult

:

/** An immutable squaring result message. */

public class SquareResult {

private final int input;

private final int output;

/** Make a new result message.

* @param input input number

* @param output square of input */

public SquareResult(int input, int output) {

this.input = input;

this.output = output;

}

@Override public String toString() {

return input + "^2 = " + output;

}

}

We would probably add additional observers to

SquareResult

so clients can retrieve the input number and output result.

Finally, here’s a main method that uses the squarer:

public static void main(String[] args) {

BlockingQueue<Integer> requests = new LinkedBlockingQueue<>();

BlockingQueue<SquareResult> replies = new LinkedBlockingQueue<>();

Squarer squarer = new Squarer(requests, replies);

squarer.start();

try {

// make a request

requests.put(42);

// ... maybe do something concurrently ...

// read the reply

System.out.println(replies.take());

} catch (InterruptedException ie) {

ie.printStackTrace();

}

}It should not surprise us that this code has a very similar flavor to the code for implementing message passing with sockets.

Stopping

What if we want to shut down the

Squarer

so it is no longer waiting for new inputs?

In the client/server model, if we want the client or server to stop listening for our messages, we close the socket.

And if we want the client or server to stop altogether, we can quit that process.

But here, the squarer is just another thread in the

same

process, and we can’t “close” a queue.

One strategy is a poison pill : a special message on the queue that signals the consumer of that message to end its work. To shut down the squarer, since its input messages are merely integers, we would have to choose a magic poison integer (everyone knows the square of 0 is 0 right? no one will need to ask for the square of 0…) or use null (don’t use null). Instead, we might change the type of elements on the requests queue to an ADT:

SquareRequest = IntegerRequest + StopRequest

with operations:

input : SquareRequest → int

shouldStop : SquareRequest → boolean

and when we want to stop the squarer, we enqueue a

StopRequest

where

shouldStop

returns

true

.

For example, in

Squarer.start()

:

public void run() {

while (true) {

try {

// block until a request arrives

SquareRequest req = in.take();

// see if we should stop

if (req.shouldStop()) { break; }

// compute the answer and send it back

int x = req.input();

int y = x * x;

out.put(new SquareResult(x, y));

} catch (InterruptedException ie) {

ie.printStackTrace();

}

}

}

It is also possible to

interrupt

a thread by calling its

interrupt()

method.

If the thread is blocked waiting, the method it’s blocked in will throw an

InterruptedException

(that’s why we have to try-catch that exception almost any time we call a blocking method).

If the thread was not blocked, an

interrupted

flag will be set.

The thread must check for this flag to see whether it should stop working.

For example:

public void run() {

// handle requests until we are interrupted

while ( ! Thread.interrupted()) {

try {

// block until a request arrives

int x = in.take();

// compute the answer and send it back

int y = x * x;

out.put(new SquareResult(x, y));

} catch (InterruptedException ie) {

// stop

break;

}

}

}Thread safety arguments with message passing

A thread safety argument with message passing might rely on:

-

Existing threadsafe data types for the synchronized queue. This queue is definitely shared and definitely mutable, so we must ensure it is safe for concurrency.

-

Immutability of messages or data that might be accessible to multiple threads at the same time.

-

Confinement of data to individual producer/consumer threads. Local variables used by one producer or consumer are not visible to other threads, which only communicate with one another using messages in the queue.

-

Confinement of mutable messages or data that are sent over the queue but will only be accessible to one thread at a time. This argument must be carefully articulated and implemented. But if one module drops all references to some mutable data like a hot potato as soon as it puts them onto a queue to be delivered to another thread, only one thread will have access to those data at a time, precluding concurrent access.

In comparison to synchronization, message passing can make it easier for each module in a concurrent system to maintain its own thread safety invariants. We don’t have to reason about multiple threads accessing shared data if the data are instead transferred between modules using a threadsafe communication channel.

Summary

-

Rather than synchronize with locks, message passing systems synchronize on a shared communication channel, e.g. a stream or a queue.

-

Threads communicating with blocking queues is a useful pattern for message passing within a single process.