< Previous lab day | Module 2 lab index | Next lab day >

Introduction

Last time you navigated a great deal of information in order to design mutagenized inverse pericams – nice work! Today you will put your designs into practice.

Michael Smith, 1993 Chemistry Nobel Prize co-winner (with Kary Mullis, inventor of PCR) for developing site-directed mutagenesis. (© The Nobel Foundation. All rights reserved. This content is excluded from our Creative Commons license. For more information, see http://ocw.mit.edu/fairuse.)

The site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) strategy you will use shares some features with the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for DNA amplification. Recall from Module 1 that PCR amplification involves multiple cycles of melting, annealing, and extending. To create one or more base-pair mutations in the product DNA, primers that have a slight mismatch to the original template can be used. At a low enough annealing temperature (~25 °C below the primer melting temperature), these nearly-complementary primers will still anneal to the template DNA, but the copies created during the extension phase will contain the mutation.

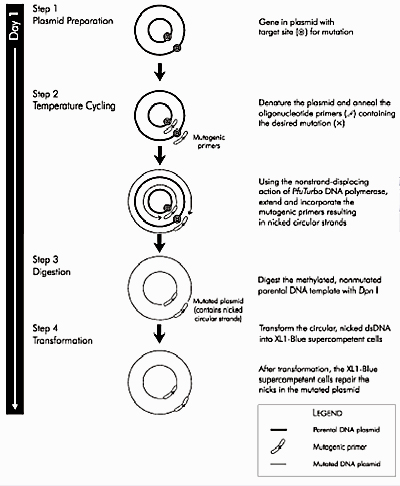

Today you will begin by combining plasmid DNA encoding wild-type inverse pericam with the mutagenic primers you designed. These will be acted upon by a DNA polymerase to generate mutant plasmid. Even more copies of the mutant plasmid can be made by introducing it into bacteria in a process called transformation, which we’ll discuss (and do!) next time. Remember that there is still parental - that is, non-mutant - DNA present in your SDM reaction mixture. In order to propagate only the mutant plasmid upon introduction into bacteria, the parental DNA is specifically digested using the DpnI enzyme prior to bacterial transformation. (Because DpnI only digests methylated DNA, the synthetically made and thus non-methylated mutant DNA is not digested.) The resulting small linear pieces of parental DNA are simply degraded by the bacteria, whereas the largely intact (but nicked) mutant DNA is actually repaired by these very same bacteria.

Overview of the QuikChange® site-directed mutagenesis method. (Courtesy of Agilent Technologies, Inc. Used with permission.)

The thermocycling reaction today will run for a little over two hours. During this incubation time, we will discuss two articles from the primary literature. We will ‘warm-up’ by discussing the paper by Heim, Prasher, and Tsien (1994). This is a short paper describing the very first attempt to mutagenize GFP, and a fine introduction to some of the concepts and methods used in this module. Next we will do a close reading of the paper that introduced inverse pericam, by Nagai, et al (2001). We will examine the construction and analysis of the inverse pericam (IPC) multi-component calcium sensor in some depth.

Now might be a good time to mention why we care about measuring intracellular calcium in the first place. Calcium is involved in many signal transduction cascades, which regulate everything from immune cell activation to muscle contraction, from adhesion to apoptosis - see for example the reviews by David Clapham in Cell (2007), or Ernesto Carafoli in PNAS (2002). Intracellular calcium (Ca2+) is normally maintained at ~100 nM, orders of magnitude less than the ~mM concentration outside the cell. ATPase pumps act to keep the basal concentration of cytoplasmic calcium low. Often calcium acts as a secondary messenger, i.e., it relays a message from the cell surface to its cytoplasm. For example, a particular ligand may bind a cell surface receptor, causing a flood of calcium ions to be released from the intracellular compartments in which they are usually sequestered. These free ions in turn may promote phosphorylation or other downstream signaling.

The proteins that bind calcium do so with a great variety of affinities, and have roles ranging from sequestration to sensing. Some calcium responses may have long-term effects, particularly in the case of transcription factors that can bind calcium. As you learned last time, calmodulin works as a calcium sensor by undergoing a conformational change upon calcium binding. Your goal today is to prepare mutant calmodulin (in the context of inverse pericam) DNA, in order to alter the affinity of the resulting protein for calcium.

References

Heim, R., D. C. Prasher, and R. Y. Tsien. “Wavelength Mutations and Posttranslational Autoxidation of Green Fluorescent Protein.” PNAS 91, no. 26 (December 20, 1994): 12501-4. [Full text]

Nagai, T., et al. “Circularly Permuted Green Fluorescent Proteins Engineered to Sense Ca2+.” PNAS 98, no. 6 (March 6, 2001): 3197-3202. [Full text]

Clapham, D. E. “Calcium Signaling.” Cell 131, no. 6 (December 14, 2007): 1047-1058.

Carafoli, E. “Calcium Signaling: A Tale For All Seasons.” PNAS 99, no. 3 (February 5, 2002): 1115-22. [Full text]

Protocols

Part 1: Primer Preparation

- Calculate the amount of water needed for each primer (forward and reverse) to give a concentration of 1 mg/mL.

- Touch-spin your primers, resuspend each in the appropriate volume of water, and touch-spin again.

- To touch spin, hold down the “short” button for 3-5 seconds, then let go.

- Calculate the dilution of primers that you need in order to have 125 ng of each primer present per 5 μL of total solution (containing both primers). Prepare 100-200 μL of this dilution and keep it on ice. Be sure to change tips between primers.

Part 2: Site-directed Mutagenesis

We will be using the QuickChange® kit from Stratagene to perform our site-directed mutageneses. Each group will set up one reaction, for their chosen X#Z mutation. Meanwhile, the teaching faculty will set up a single positive control reaction, to ensure that all the reagents are working properly. You should work quickly but carefully, and keep your tube in a chilled container at all times. Please return shared reagents to the ice buckets on the front bench when you are done with them.

- Read through the following protocol and prepare all calculations before beginning physical manipulations of your samples.

- Get a PCR tube and label the top with your mutation and lab section (write small!). Add 43 μL of “Master Mix” - containing buffer and dNTPs - to your tube. Be sure to use a fresh pipet tip, as several groups will share each aliquot of Master Mix!

- Add 2 μL of template DNA (“IPC plasmid”) to the reaction tube.

- Note: mutagenesis reactions are expected to run smoothly with 5-50 ng of plasmid DNA. You have been given a 1:200 dilution of miniprep DNA.

- Add 5 μL of diluted primer solution (containing both forward and reverse primers) to the tube. The volume of the reaction should be now be 50 μL.

- Finally, add 1 μL of PfuTurbo DNA polymerase (do not mix the enzyme stock when you take from it) to the reaction using your P20, and mix the reaction thoroughly by pipetting with your P200 set at 40 μL.

- Once each group is ready, we will begin the thermocycler, under the following conditions:

| SEGMENT | CYCLES | TEMPRATURE (° C) | TIME |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 95 | 30 sec |

| 2 | 18 | 95 | 30 sec |

| 55 | 1 min | ||

| 68 | 5 min | ||

| 3 | 1 | 4 | indefinite |

- After the cycling is completed, set aside 10 μL of your reaction in a well-labeled eppendorf tube (mutation, lab section, team colour). You will need this undigested sample next time.

- Add 1 μL of DpnI to the remaining reaction mixture in the PCR tube, and pipet to mix. Samples will be incubated for one hour at 37 °C.

- This final incubation step will take us past lab closing time, at which point your digested (and undigested) DNA will be frozen until next time.

Part 3: Journal Article Discussion

During the production of the mutagenized DNA, we will discuss the two journal articles cited in the introduction. The purpose of this discussion will be two-fold: 1) to familiarize ourselves with the history of protein design, and 2) to continue to explore ways of talking about the scientific literature. (Probably you are all pros after the Module 1 journal clubs!)

As you read the paper by Heim, Prasher, and Tsien, consider the following questions.

- What are the advantages of GFP compared to synthetic fluorescent dyes, and what are its limitations? Which of these limitations are Heim et al. trying to address?

- What methods did the authors use for mutagenesis, and how do they compare to the method we are using?

- How were mutagenic proteins initially selected, and how were the chosen ones further analyzed?

- What is the significance of the different wild-type protein fractions shown in Figure 1?

- If GFP maturation does not require any cofactors for a chemical reaction, why does it take four hours? What lines of evidence suggest the absence of cofactors?

- In what part(s) of the protein were useful amino acid substitutions found?

When you arrive in lab today, each group will be assigned one of the following numbered topics to present to and discuss with the rest of the class. The same group will cover topics #1 and #8. You should be somewhat familiar with the whole Nagai et al paper by now, but will have some time in-class to refresh your memory and become the resident expert in one of the following areas (note that sometimes the Results/Discussion text pertaining to a particular figure may be out of numerical order - e.g., Fig. 4 is written up after Fig. 5):

- Introduction, Methods (Gene Construction) and Figure 1

- Consider: What is a chimeric protein? A circularly permuted one?

- How does the chimeric protein pericam work as a sensor? (No need to for details about different types of pericams yet.)

- Briefly summarize how pericam was constructed at the gene level. What changes had to be made to express pericam in mammalian rather than bacterial cells?

- Figure 2

- What do the authors learn about cpEYFP structure from the absorbance spectra?

- Compare the wavelength used for testing pericam with the excitation maximum of cpEYFP. Why might they be slightly different?

- Besides making the mutations shown in Table 1, what did the authors have to do to make a working (fluorescent, calcium-sensitive) pericam?

- What was the dynamic range (intensity change with calcium addition) of the first working cpEYFP?

- Table 1 (Mutations) and Figure 3, A-I (focus on D-F)

- Describe the three types of pericam initially constructed and tested and how they respond to calcium.

- What kinds of amino acid substitutions were made, and why might they cause the noted effects?

- Table 1 (Kd) and Figure 3, J-L

- This set of figures is very similar to the one you will eventually create for your lab reports. It is not described at length in the text, so take a moment to decipher the axes and results as best you can, using outside resources if necessary.

- Figure 4

- How does flash-pericam improve upon previous limitations to imaging calcium in the nucleus and cytosol?

- What chemicals can be used to create step-changes in intracellular calcium, and how might they work?

- Figure 5

- How did the authors calibrate calcium levels?

- Compared to the other pericams, what’s special about the way split-pericam functions?

- What are the limitations of using split-pericam as a calcium sensor?

- Figure 6

- What modifications were made to pericam for organelle-level study, and how does the use of pericams improve upon previous procedures?

- What were the authors able to learn about calcium transients in different organelles?

- Wrap-up

- Describe some other (not pericam-based) calcium indicators.

- How does FRET work, and what are the pros/cons of using FRET-based sensors?

Finally, you should all consider the similarities and differences between the research described in the papers above and the research that you are undertaking in this module.

For Next Time

- Calculate how much (weight) plasmid DNA you used in your mutagenesis reaction, assuming that the miniprep procedure results in typical concentrations of 1 μg/μL.

- Let’s take a moment to explore the smallest component of the inverse pericam construct. What protein is the M13 peptide derived from, and what does this protein usually do? Specifically, you should describe its molecular and macroscopic function, in a sentence or two.

- Unlike PCR for amplification, which exhibits exponential growth, site-directed mutagenesis causes a linear increase in the amount of desired DNA product. This is because DNA amplification can occur only from the original template in SDM, never from a copy of that template. Why should this be? Remember that DNA can only be synthesized in the 5’ to 3’ direction. Moreover, the DNA that is copied from the template exists in nicked formed, not as an intact circle. Finally, keep in mind that your forward and reverse primers are directly complementary. Use these three facts to draw a picture demonstrating why SDM will only produce copies of the original template DNA, and briefly explain it. Be sure your diagram/explanation explicitly answers the question posed.

Reagent List

- QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit from Stratagene

- 10X Reaction Buffer (100 mM KCl, 100 mM (NH4)2SO4, 200 mM Tris-HCl, 20 mM MgSO4, 1% Triton® X-100, 1 mg/mL BSA)

- _PfuUltra_® DNA polymerase (2.5 U/μL, 1 μL per rxn)

- dNTP mix (proprietary mix, 1 μL per rxn)

- Dpn I (10 U/μL)