If crop production is to be increased through intensification, without significantly expanding harvested area ), then crop yield (which is the ratio of production to area) must increase. This raises the following important questions:

- How much can crop yields be increased above present levels?

- What will be required to achieve increased yields?

- What are the possible environmental consequences of significant yield increases?

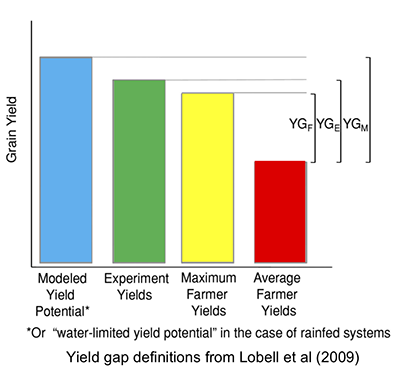

Class 5 provides a preliminary assessment of these questions with two papers that address the “yield gap”: the difference between potential yields achieved with ideal management practices and average farmer yields achieved in the field. It is especially important to recognize practical and theoretical limits on both potential and actual yields since yield improvement is a possible option for achieving sustainable increases in global food production.

© Annual Reviews. All rights reserved. This content is excluded

from our Creative Commons license. For more information,

see https://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use.

Both of our Class 5 readings focus on cereal yields because of the important role of cereals in supplying food energy. The paper by Lobell et al. (2009) defines different types of yield gaps that rely on different methods for estimating yield potentials. The accompanying figure summarizes these definitions. The ideal site-specific yield potential is an upper limit on yield that is achieved when the crop is not subject to stress from controllable factors, such as nutrient limitations. Uncontrollable site-specific factors that affect yield potential include solar radiation, temperature, and water availability (for rainfed systems). The potential value can be inferred from crop growth models, field experiments, or observed maximum farmer yields. The authors suggest that, although it may be possible to increase yield potential, that will require fundamental changes in plant function that go beyond improvements in management practices. Examples include the high yield cereals bred during the twentieth century “Green Revolution” discussed in Class 11.

The Lobell et al. survey of observed yield gaps indicates that average farmer yields range from only 20% of irrigated yield potential for rainfed maize in Africa to nearly 80% or higher for wheat and rice in irrigated areas with adequate nutrient application and good pest control. The authors’ list of factors responsible for yield gaps include stresses related to imperfect nutrient and water applications, planting practices, and seed quality, as well as pests, storm damage, and soil deficiencies. It is difficult to identify which factors predominate in a given location and season. The data presented in the paper show the large variability in yield observed even in relatively homogeneous regions such as the US corn belt. This variability does not seem to be explained primarily by farmer decisions but, rather, reflects the ever-changing aggregate effect of all the management and environmental factors listed above.

The short paper by Mueller et al. (2012) summarizes a particular data and model-based study of yield gap variability. The paper’s global map of the fraction of; yield potential achieved , which is a convenient normalized measure of yield gap, is included in S8, together with a summary of the procedure used to obtain it. Mueller et al. also consider the effects of nutrient and irrigation practices on yield in different regions. Although the analysis is relatively simplified and the data needed for a comprehensive global study are limited the paper makes a reasonable case that crop production in some regions (e.g. sub-Saharan Africa) could be significantly increased above current levels through expanded use of fertilizers and irrigation.

The optional readings by Licker et al. (2010) and Ray et al. (2012) provide further discussion of yield gaps and yield saturation. Ray et al. suggest that it may not be either; feasible or desirable to close yield gaps. There is no guarantee that further increases in inputs can actually raise yields significantly for all crops. Even if they can, the environmental impacts may not be acceptable.

A major question that remains after reviewing these readings is whether it should be possible to increase yield potential through breeding and genetic engineering efforts that could duplicate some of the successes of the Green Revolution. This question is considered but not really resolved in Cassman et al. (1999), a required reading in Class 11. It seems likely that crop production increases will be achieved primarily by bringing actual yields closer to current yield potentials. New breeding and genetic engineering developments could play an important role in this process by helping to reduce plant stress. But we cannot reasonably expect another Green Revolution to solve our food security problems by increasing the yield potentials of all the major staple crops. We will return to this topic in subsequent classes.

Required Readings

Crop Yield Overview

- David B. Lobell, Kenneth G. Cassman, and Christopher B. Field. 2009. “Crop Yield Gaps: Their Importance, Magnitudes, and Causes.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 34: 179–204.

- Nathaniel D. Mueller, James S. Gerber, et al. 2012. “Closing Yield Gaps Through Nutrient and Water Management.” Nature. 490, no. 7419: 254–257.

Optional Readings

Variations in Crop Yield and Yield Gaps

- Rachel Licker, Matt Johnston, et al. 2010. “Mind the Gap: How Do Climate and Agricultural Management Explain the ‘Yield Gap’of Croplands Around the World?” Global Ecology and Biogeography. 19, no. 6: 769–782.

Crop Yield Saturation

- Deepak K. Ray, Navin Ramankutty, et al. 2012. “Recent Patterns of Crop Yield Growth and Stagnation.” Nature Communications, 3, no. 1: 1–7.

Discussion Points

- Do you think it should be possible to increase potential yields without increasing water or nutrient requirements? What would you need to know in order to give an informed answer to this question?

- How would you structure a detailed investigation of yield variability within a given region, such as East Africa? Try to identify, as specifically as you can, the data and methods you would need to use.