© John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. This content is excluded

from our Creative Commons license. For more information,

see https://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use.

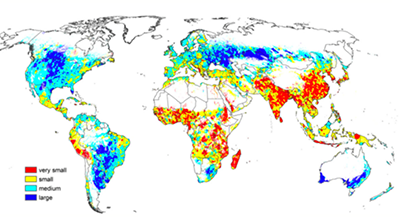

It is important when reviewing options for improving food security to consider the full range of production systems that feed the global population. The background data presented in S10 show that farms vary greatly in size, income, and productivity. In particular, the larger more profitable farms that are typical in the US, Canada, Australia, and parts of South America represent one end of a continuum. Elsewhere, much smaller low-income farms are more common. Very small farms of only a few hectares dominate agriculture in China, India, and Africa and provide food and limited cash income for about 2 billion smallholders, roughly one quarter of the global population.

In this class and in S10 we examine the smallholder agriculture system that still feeds much of the developing world. We shall see that the survival of the smallholder farmer is very much in question. If smallholder agriculture declines there will need to be substantial changes in the food production and distribution systems that serve much of the world’s population. That is why both smallholder and larger commercial farming need to be part of any discussion of global or regional food security.

We focus our discussion on sub-Saharan Africa because this is a region where smallholders are especially vulnerable to the pressures imposed by rapid population growth, difficult agroclimatic conditions, and changing economic incentives. The twentieth century Green Revolution that transformed smallholder agriculture in Asia and parts of Latin America largely bypassed sub-Saharan farmers (this topic is discussed further in Section 4). These farmers are still struggling with low crop yields, inadequate infrastructure, poor access to inputs and markets, and insufficient resources to invest for the future.

Smallholders in Africa and elsewhere are frequently very poor, with minimal cash income coming primarily from contract labor or off-farm employment. Many of them need to grow a sizable fraction of the food they consume. When conditions such as a drought or pest outbreak make this difficult and they have limited reserves these farmers may not have enough to eat. Smallholders make up about half of the world’s malnourished population, despite the fact that they normally produce much of the food grown in their own countries. These farmers contribute significantly to food production but they are also especially vulnerable to food insecurity.

The challenges faced by smallholders in sub-Saharan Africa are discussed in the readings by Jayne et al. (2010) and Carr (2001). The economic challenges mentioned by Jayne et al. include shrinking farm sizes, decreasing productivity, marketing problems, limited off-farm employment opportunities, and changing international trade and development policies. Carr provides useful historical context and emphasizes agronomic challenges, including the need for better access to fertilizer, higher yield cultivars suitable for local conditions, and expanded irrigation to reduce water stress on rainfed crops. Similar challenges arise in varying degrees throughout the world but they are particularly problematic in sub-Saharan Africa, where farm incomes and assets are unusually low, soil fertility is often poor, climate extremes can be severe, and state support of agricultural development can be erratic and underfunded. The plots in the optional reading by Rapsomanikis (2015) provide convenient summaries of smallholder economic life in several developing countries, including some in Africa. Relevant statistics are also provided in S13.

The issues identified by Jayne et al. and Carr raise the question of whether smallholder agriculture can be expected to meet the food needs of Africa’s growing population. This question is addressed in the next two papers. Larson et al. (2016) argue that the high-input smallholder model that has been so successful in Asia is the best option for Africa. By contrast, Collier & Dercon (2014) favor more reliance on larger commercial operations, which they feel benefit from economies of scale. The two papers agree that there is a need for a mix of small, medium, and large farms, although they differ on the relative importance of each category. Their debate is central to African development discussions.

One aspect of the smallholder vs. commercial farm debate is the feasibility of increasing crop yields, which tend to be low in sub-Saharan Africa for farms of all sizes. The role of yield is addressed in the paper by van Ittersum et al. (2016), which considers whether food needs in selected African countries could be met by closing yield gaps. (see S6). Their analysis indicates that some of the larger countries (e.g. Nigeria and Kenya) will have difficulty meeting their needs with domestic production, even with nearly complete elimination of yield gaps, while others (e.g. Ethiopia) have a better chance. Although closing yield gaps may not be sufficient to feed some sub-Saharan countries with domestic production, food demands could still be met with imports, particularly if per capita incomes grow enough. In these countries food security is closely tied to economic development outside as well as inside the agricultural sector.

The choice for governments and donors between encouraging smallholder vs. larger commercial farming is difficult since there are compelling arguments on both sides. However, the future of global food security could depend significantly on the priority given to each alternative.

Required Readings

Challenges of Smallholder Agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa

- T. S. Jayne, D. Mather, and E. Mghenyi, 2010. “Principal Challenges Confronting Smallholder Agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa.” World Development, 38, no. 10: 1384–1398.

- S. J. Carr. 2001. “Changes in African Smallholder Agriculture in the Twentieth Century and the Challenges of the Twenty-First.” African Crop Science Journal, 9, no. 1: 331–338.

Smallholder vs. Commercial Agriculture for Sub-Saharan Africa

- D. F. Larson, R. Muraoka, and K. Otsuka, 2016. “Why African Rural Development Strategies Must Depend on Small Farms.” Global Food Security, 10, 39–51.

- P. Collier and S. Dercon. 2014. “African Agriculture in 50 Years: Smallholders in a Rapidly Changing World?” World Development, 63, 92–101.

Closing Yield Gaps in Africa

- M. K. Van Ittersum, L. G. Van Bussel, et al. 2016. “Can Sub-Saharan Africa Feed Itself?” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113, no. 52: 14964–14969.

Optional Reading

Smallholder Economic Profiles

- G. Rapsomanikis. 2015. “The Economic Lives of Smallholder Farmers: An Analysis Based on Household Data from Nine Countries (PDF - 3.6MB).” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

Farm Size and Distribution

- S. K. Lowder, J. Skoet, and T. Raney. 2016. “The Number, Size, and Distribution of Farms, Smallholder Farms, and Family Farms Worldwide.” World Development, 87, 16–29.

Discussion Points

- What is your conclusion about the merits of directing government and donor resources to smallholder vs. larger commercial farming? How convincing do you find the arguments in the two readings on this issue?

- Based on what you have read for this class, what would you say are the most significant factors that distinguish agricultural development in Africa from other regions? What are the prospects for African agriculture and food security?

- The reading by Collier & Dercon includes an extended discussion of labor productivity and migration, implying that migration is the best way to increase the low labor productivity of smallholders and, consequently, to reduce their poverty. Do you think there is a chance that improved technology could also increase labor productivity. For example, how about more extensive use of fertilizers and herbicides?