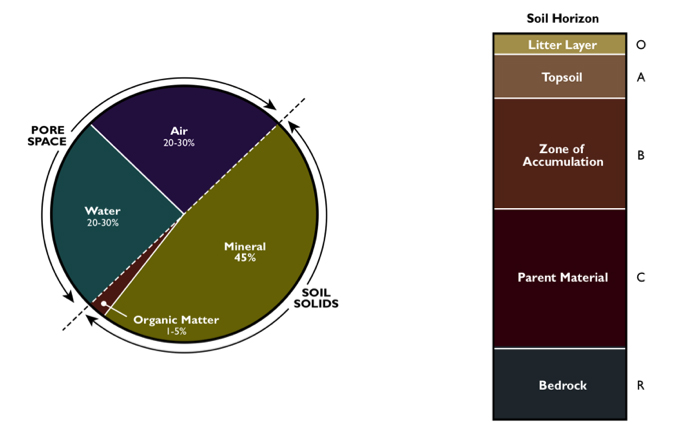

Soil is comprised of inorganic minerals, organic matter, water, and air. It typically forms in layers (or soil horizons) when it develops from the weathering and transport of mineral or organic parent material (Figure S9.1).

Figure S9.1: a) Primary components of soil, fractions are representative but change over time.

b) Soil horizons found in a typical agricultural soil profile. From Brady and Weil (2002).

© Prentice Hall, Inc. All rights reserved. This content is excluded from our Creative Commons license.

For more information, see https://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/.

The chemical and biological composition of the soil components as well as their physical arrangement affect the movement and retention of air, water, and nutrients in the subsurface. Bulk soil has a number of properties that collectively determine its fertility or quality for agricultural applications. A concise discussion of these properties as well as the soil column that includes the crop root zone is provided in the optional Class 6 reading by McCauley et al. (2005).

The short list of agriculturally relevant soil properties given below can be used to concisely characterize a particular soil, This list is constructed from suggestions by NCERA-59, an inter-state group in the US (Doran and Parkin, 1994) and by the Soil Health Institute (Wander, 2019):

Physical properties:

Soil texture

Rooting depth

Bulk density

Infiltration rate

Water holding capacity

Wet aggregate stability

Penetration resistance erosion rating

Chemical properties:

pH

Total nitrogen (N)

Total organic carbon (TOC)

Electrical conductivity (EC)

Phosphorus (P)

Potassium (K)

Base saturation

Cation exchange capacity (CEC)

Biological properties

Carbon mineralization

Nitrogen mineralization

It is common to use quantitative or categorical indices derived from soil property values to assess the suitability of a given soil for a given crop. Recent FAO-funded data acquisition efforts have produced global soil property data sets that have been harmonized to reconcile different national measurement and reporting methods (FAO, 2012). The functions given in Figure 2 of Zabel et al. (2014) from Class 4 provide simple examples of how soil properties can be mapped to soil suitability indices. Fischer et al. (2012) describe a more complex soil suitability classification approach based on some of the soil properties listed above.

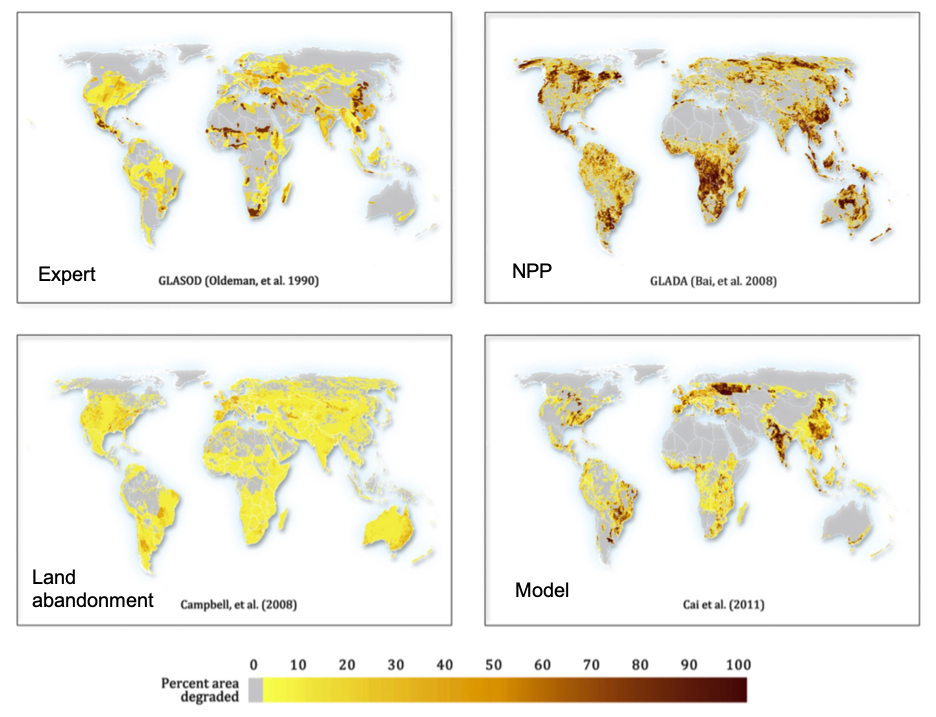

Unfortunately, data limitations make it difficult to use such methods to analyze temporal trends in soil quality or to identify where agricultural practices are either degrading or improving soil. Current approaches for looking at soil quality trends are imperfect and controversial. Gibbs and Salmon (2015) is one of the few papers that compares different approaches for mapping global soil degradation trends (expert opinion, satellite-derived net primary productivity, biophysical models, and abandoned cropland). This paper shows large variations across different estimates of regional and total soil degradation (see Figure S9.2), suggesting that we still do not really know how much agriculture has changed the soil resources needed to grow food. This uncertainty complicates global assessments of the impacts of different agricultural practices on soil health.

However, there is still ample local evidence that soil quality has declined in particular agricultural areas that have experienced intense cultivation or grazing pressure. These include parts of North and South America, India, China, and sub-Saharan Africa. In these areas it is likely that yield has suffered or, in some cases, that the land is no longer suitable for agriculture.

Figure S9.2: Four different estimates of global soil degradation with a common color scale (percent of land

degraded) and 20km resolution, ca. 1990 (GLASOD) and 2010 (others), from Gibbs and Salmon (2015).

Courtesy Elsevier, Inc., http://www.sciencedirect.com. Used with permission.

References

Nyle C. Brady and Ray R. Weil. 2002. The Nature and Properties of Soils, 13th Edition. Prentice Hall. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. 960 p. ISBN: 9780130167637.

John W. Doran and Timothy B. Parkin. 1994. “Defining and Assessing Soil Quality.” Defining Soil Quality for a Sustainable Environment, 35: 1–21.

FAO/IIASA/ISRIC/ISSCAS/JRC. (2012). “Harmonized World Soil Database v 1.2.” FAO, Rome, Italy and IIASA, Laxenburg, Austria.

Günther Fischer, F. Nachtergaele, et al. 2012. “Global Agro-Ecological Zones (GAEZ v3. 0) - Model Documentation.”

H. K. Gibbs and J. M. Salmon. 2015. “Mapping the World’s Degraded Lands.” Applied Geography, 57, 12–21.

McCauley, A., Jones, C., and Jacobsen, J. (2005). “Basic Soil Properties (PDF).” Soil and Water Management Module. 1, no. 1: 1–12. Montana State University Extension Service.

Michelle M. Wander, Larry J. Cihacek, et al. 2019. “Developments in Agricultural Soil Quality and Health: Reflections by the Research Committee on Soil Organic Matter Management.” Frontiers in Environmental Science, 7, 10.3389/fenvs.2019.00109.

Florian Zabel, Birgitta Putzenlechner, and Wolfram Mauser. 2014. “Global Agricultural Land Resources—A High Resolution Suitability Evaluation and Its Perspectives until 2100 under Climate Change Conditions.” PLoS One, 9, no. 9.