In Class 12 we consider agroecology, which is as much a philosophy and a movement as a set of techniques for growing crops. As the name implies, this perspective views a farm or larger agricultural area as an ecosystem to be managed for human benefit, primarily food production. The intent of the agroecological approach is to rely on practices that work in harmony with natural processes. This may or may not increase yield over conventional (aka Green Revolution) approaches and may or may not alleviate particular environmental problems. “Agroecological” is a broader term than “organic” since organic practices are more regulated and often more restrictive. However, we generally use the terms interchangeably in this discussion.

The practices most commonly associated with agroecology are summarized in the reading by Wezel et al. (2014), which is oriented towards conditions in temperate developed countries. The paper by Pretty (2008) takes a broader global view and provides more discussion of yield and environmental aspects. Both papers are longer than necessary but can be read efficiently. Wezel et al. conveniently summarize agroecological practices in Table 3, which gives the essence of the paper. These practices are divided into “Efficiency increase and substitution” and “Redesign” categories and are discussed in more detail in Sections 3 and 4 of the paper. Wezel et al. note the increased labor requirements of some agroecological practices, such as intercropping and non-chemical pest management. This is an important issue, especially in areas with labor shortages or high labor costs.

Pretty provides in his Section 5 a short list of practices similar to those identified by Wezel et al. and then discusses some of the possible impacts of these practices in Sections 6-8 of the paper. He ends with the somewhat surprising quote, considering the paper’s optimistic assessment (in Section 6) of agroecological yield performance in developing countries:

“ … In this context, it is unclear whether progress towards more sustainable agricultural systems will result in enough food to meet current needs in developing countries, let alone future needs after continued population growth (and changed consumption patterns) …”

This quote recalls the analysis of van Ittersum et al. (2016) from Class 7, which suggests that some sub-Saharan African countries may not be able to meet their food needs even if their yield gaps are greatly reduced. The optional FAO (2013) report on agroecology is a collection of many papers on specific topics that are beyond the scope of our discussion.

Agroecology (especially organic production) is generally associated with reduced inputs of pesticides and synthesized inorganic nitrogen fertilizers. However, an agroecological farm may still consume inorganic nitrogen (e.g. in manure) in quantities that are comparable to the nitrogen used by a conventional farm that grows the same crops. A similar comment applies to irrigation water. Further details on the external input requirements and environmental impacts of agroecological farming are provided in the optional papers by Clark and Tilman (2017), Cassman at al (2002), and Robertson and Vitousek (2009).

Clark and Tilman summarize results from life cycle assessments of a limited number of environmental indicators in a direct comparison of conventional and agroecological production systems. They also compare these indicators for different food groups. They conclude that the two production systems have similar nutrient-related impacts on the environment. They also conclude that meat consumption has significantly more impact on their environmental indicators than the production system. Cassman et al. and Robertson and Vitousek present careful analyses of agricultural nitrogen inputs and related environmental impacts. These relatively long papers are worth reading for the useful information they provide on the origin and fate of nitrogen in its many different forms. They confirm that differences in the way nutrients are processed in the two production systems are subtle and still not well understood. In particular, it is not clear that natural alternatives to synthetic nitrogen fertilizers could meet current, let alone projected, global production requirements.

© FAO. All rights reserved. This content is excluded from our Creative Commons license. For more information, see https://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use.

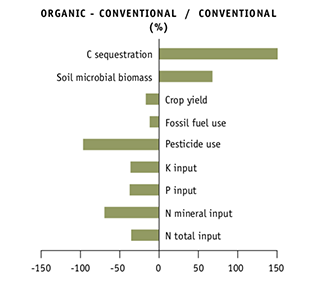

These readings leave us with the question of whether the agroecological approach can achieve the crop yields needed to meet the food needs of up to 10 billion people later in this century. This scale-up question is rarely addressed in publications that advocate agroecological methods. There is no doubt that individual farms can be operated with minimal synthetic nutrient and pesticide inputs if enough effort is expended and increased yield is not a high priority. An example is described in the attached chart that summarizes a 21-year comparison of agroecological and conventional methods at the DOK experimental farm in Switzerland (UNFAO, 2014; Fliessbach, 2007). However, it is still unclear whether agroecology can be a feasible alternative to modern Green Revolution agriculture, which currently produces a major part of the global food supply.

Seufert and Ramankutty (2017) provide a reasonably objective meta-analysis of agroecological performance based on studies carried out mostly in developed countries. The results are summarized in multi-dimensional diagrams that compare agroecological and conventional production systems. The paper states that agroecological (or organic) yields are generally 20% lower than those from conventional systems, with significant variability depending on the crop and on specific management practices. The rankings for other performance measures vary. Crop-specific details of the analysis are provided in the paper’s Supplementary Information and more information on organic yields is given in the optional reading by Seufert and Ramankutty (2012).

An important qualification of the Seufert and Ramankutty work is that much of the supporting data are from developed countries where conventional yields are significantly higher than in most developing countries. Also, reliance on data from certified “organic” farms, as compared to the broader set of agroecological farms, may skew the results to lower yields (because, for example, synthetic fertilizers and chemical pesticides are not allowed in organic production). In any case, agroecological yields that are similar, or even 20% lower, than conventional yields in developed countries could still provide a substantial increase over current production levels in developing countries.

Although the papers discussed in this class do not give a definitive assessment of agroecosystem performance they do suggest that flexible agroecological methods may be beneficial in developing countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, where input cost, preservation of soil quality, and resilience are especially important and labor cost is less of an issue. Some agroecological practices may also be attractive for larger farms in exporting countries if these practices can provide substantive environmental benefits without major reductions in yield. A tangible example is the adoption of no-till agriculture in the drier portions of the US Great Plains. This is motivated by a distinct improvement in water retention when tillage is reduced.

It may be that the most important benefits of agroecology are its emphasis on efficient resource use, biodiversity (see photo below), non-chemical pest management, and improvement of long-term soil quality. All of these contribute to the sustainability and resilience of the overall agricultural system.

© Ravi Prabhu. All rights reserved. This content is excluded from our Creative Commons license.

For more information, see https://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use.

Required Readings

Summary of agroecological practices

- Alexander Wezel, Marion Casagrande, et al. 2014. “Agroecological Practices for Sustainable Agriculture. A Review.” Agronomy for Sustainable Development. 34, no. 1: 1–20.

- Jules Pretty. 2008. “Agricultural Sustainability: Concepts, Principles and Evidence.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 363, no. 1491: 447–465.

Comparison of Agroecological and Conventional Performance

- Verena Seufert and Navin Ramankutty. 2017. “Many Shades of Gray—the Context-Dependent Performance of Organic Agriculture.” Science Advances. 3, no. 3, e1602638.

- Verena Seufert and Navin Ramankutty. 2017. “Many Shades of Gray—the Context-Dependent Performance of Organic Agriculture. Supplementary Information.” Science Advances. 3, no. 3, e1602638.

Optional Reading

Agroecology Overview

- UN FAO. 2015. “Agroecology for Food Security and Nutrition: Proceedings of the FAO International Symposium.” International Symposium on Agroecology for Food Security and Nutrition. Rome, Italy. 426 pp.

Nitrogen in Agriculture

- Michael Clark and David Tilman. 2017. “Comparative Analysis of Environmental Impacts of Agricultural Production Systems, Agricultural Input Efficiency, and Food Choice.” Environmental Research Letters. 12, no. 6: 064016.

- Kenneth G. Cassman, Achim Dobermann, and Daniel T. Walters. 2002. “Agroecosystems, Nitrogen-Use Efficiency, and Nitrogen Management.” AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment. 31, no. 2: 132–140.

- G. Philip Robertson and Peter M. Vitousek. 2009. “Nitrogen in Agriculture: Balancing the Cost of an Essential Resource.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 34, 97–125.

Comparison of Agroecological and Conventional Crop Yields

- Verena Seufert, Navin Ramankutty, and Jonathan A. Foley. 2012. “Comparing the Yields of Organic and Conventional Agriculture.” Nature. 485, no. 7397: 229–232.

- Andreas Fliessbach, Hans-Rudolf Oberholzer, et al. 2007. “Soil Organic Matter and Biological Soil Quality Indicators After 21 Years of Organic and Conventional Farming (PDF).” Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment. 118, no. 1–4: 273–284.

Discussion Points

- Do you think that agroecological and/or organic methods could feed the current or projected 2050 global populations with the current FAOSTAT global average diet? How might your answer change with a different diet?

- What was your impression of organic agriculture coming into this class? How has it changed, if at all?

- Elaborate on the pros and cons of donors and governments encouraging agroecological methods in developing countries, especially in Africa. Should we apply different criteria in these countries (as opposed to developed countries) when assessing the desirability of agroecology? Is agroecology a luxury for the rich or an option that could be very successful in the developing world because it builds on tradition and requires less capital?