In Class 11 we examine more closely the high input agricultural systems that now prevail in somewhat different forms in developed countries and a large part of the developing world. These systems, both the large and small farm versions, rely on modern high yield cultivars, extensive irrigation, and synthetic fertilizers. Our discussion builds on readings covered earlier, especially in Section 3, as well as new readings that focus on the feasibility of further increasing production with the high input model.

© Springer Nature. All rights reserved. This content is excluded from our Creative Commons license. For more information, see https://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use.

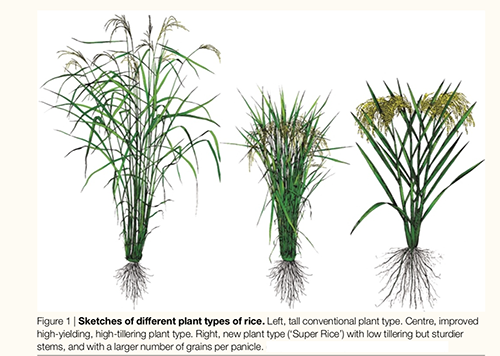

In the mid-twentieth century the high input modern cultivar approach widely used in European and North American agriculture was extended, with considerable success, to Asia and parts of Latin America. This so-called “Green Revolution” was driven by selective breeding programs that developed hardier, higher yielding varieties of wheat and rice (see attached sketch from Khush (2001)). As the new varieties were adopted they increased cereal production and provided substantial improvements in food security. The short article by Hazell (2002) summarizes the history and accomplishments of this transformation.

The Green Revolution introduced environmental problems, as well as greater food security, to the countries where its methods were adopted. Many of these problems were related to the increased use of fertilizers, irrigation, and pesticides that were needed to fully realize the higher yield potentials of the new varieties. This increase in inputs, which was often not carefully controlled, led to the adverse environmental impacts now widely associated with modern agriculture and discussed in Class 6. The paper by Pimental and Pimental (1990) provides a brief summary. More details on relevant economic issues, environmental impacts, and farm consolidation are provided in a longer optional reading by Hazell (2010). The optional reading by Khush (2001) provides background on the genetic methods used to breed Green Revolution cultivars.

Green Revolution technology transformed much of smallholder agriculture in India and China from the small farm/low input model to the more productive small farm/high input model introduced in the Section 4 Overview. The transformation was most successful in areas with sufficient water to support irrigation systems and with ready access to fertilizers and locally appropriate seeds. Although efforts were made to introduce the Green Revolution to Africa, these were less successful, leaving a sizable and rapidly growing population with the lower yields, less reliable production, and poverty generally associated with low input smallholder farms. This aspect of the Green Revolution is briefly discussed in Carr (2001) in Class 7.

Does the success of the twentieth century Green Revolution imply that the best way to achieve global food security is to extend intensification more widely, perhaps by increasing production in the major exporting nations, but certainly by increasing it in Africa and the parts of Asian and Latin America that have been left behind? That will require resolution of the issues raised by Carr, including development of irrigation infrastructure and more ready access to inputs and markets.

The possibility of further intensifying the Green Revolution approach is addressed in the widely cited paper by Cassman (1999). He considers the possibility of raising cereal production by increasing potential (unstressed) yield (Class 5), controlling and improving soil quality (Class 6), and using precision agriculture to improve the efficiency of nitrogen application (Class 9). In each case, his conclusion is that small rather than revolutionary improvements are most likely. Cassman mentions that new genetic engineering methods could conceivably have a major impact if they can increase yield potential significantly beyond what has already been achieved with traditional selective breeding. However, the primary contribution of these methods so far has been to bring actual yields closer to existing potential yields by reducing stress, primarily from losses to pests.

Soil quality improvements could also be beneficial but require more than just additional nutrient application, as illustrated in the paper’s examples of recent yield declines in irrigated rice systems. Post-Green Revolution yield declines have also been observed in other settings (see Class 5). Although precision agriculture holds promise for improving the efficiency of nutrient and irrigation water application it focuses on bringing actual yields up to potential levels by reducing stress, rather than on increasing potential yield. The overall implication of Cassman’s analysis is that site-specific measures to close yield gaps could make substantive differences where actual yields are much lower than yield potential (e.g. in areas where low input smallholder agriculture still dominates). But there is relatively little reason to believe that there will be another round of dramatic increases in cereal yield potential by mid-century. This raises serious questions about the feasibility of feeding an additional 2 or 3 billion people with intensified Green Revolution methods.

In food security, as in climate change, it seems that the most realistic options are those that combine a number of measures that may have relatively small effect in themselves but may have significant impact when taken together. We return to this idea in Section 5, after a look at the Agroecology alternative to the Green Revolution.

Required Readings

Background on the Green Revolution

- Peter B. R. Hazell. 2002. “Green Revolution: Curse or Blessing? (PDF)” No. REP-9450. Washington, DC (USA), IFPRI. 3 p.

- D. Pimentel and M. Pimentel 1990. “Comment: Adverse Environmental Consequences of the Green Revolution.” Population and Development Review, 16, 329–332.

Possibilities of Further Extending the Green Revolution’s Intensification Approach

- Kenneth G. Cassman. 1999. “Ecological Intensification of Cereal Production Systems: Yield Potential, Soil Quality, and Precision Agriculture.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 96, no. 11: 5952–5959.

Optional Reading

Green Revolution impacts

- Peter B.R. Hazell. 2010. “Asia’s Green Revolution: Past Achievements and Future Challenges.” Chapter 1.3 in Rice in the Global Economy. Strategic Research and Policy Issues for Food Security. S. Pandey, D. Byerlee, et al. (Eds). IRRI. Manila.

Genetic Background for the Green Revolution

- Gurdev S. Khush. 2001. “Green Revolution: the Way Forward.” Nature Reviews Genetics, 2, no. 10: 815–822.

Discussion Points

- Based on what you have read in class, is it likely that large-scale high input agriculture will spread throughout the areas where it is feasible and feed the rest of the world through exports? In this model, which is believed by some to be inevitable, small farms, either high or low input, will essentially disappear, replaced by a more industrialized global food system.

- Do you agree with Hazell and others who believe that the Green Revolution’s environmental problems were due to farmer limitations and policy failures rather than any intrinsic deficiency in Green Revolution methods?

- Although the Green Revolution may have its limitations, it seems to have been successful at increasing national production. Should we be looking for an alternative when considering the future or learn from the past and improve the basic model so production can be increased further and undesirable side effects minimized?