In this section, Shariann Lewitt discusses why she intentionally chose a problematic reading (the article “What is Fantasy?”), what she hoped students would get from it, and how the class actually reacted.

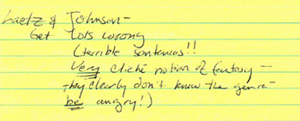

An excerpt from the instructor’s notes, highlighting key topics for class discussion

This semester I intentionally assigned an article that I think is based on a caricatured, uniformed idea of what fantasy fiction is and is about. The authors seem to know only the very worst of the genre, and don’t look at any kind of literary fantasy. Their article only discusses their idea of a couple of major, big motion pictures and a few book covers, and they seem to assume that’s all there is. There are a number of really bad assumptions about all of fantasy on that basis.

I wanted my students to see that, even with their bad assumptions, the authors do pose a lot of interesting questions: How do we know what genre is? How are we able to make that identification? What are the markers of genre, and how do we know what they are? As readers and writers, we know when we see the hallmarks of the genres that we create, that we study, that we love. How do we know those things?

My first question to the class was, “What do you think?” Their responses were basically, “Well, I guess it was okay. They had some things to say there.” So I tried to lead them along a little, I asked them “How did you feel about this article? Did anybody have any argument with this article?” But nobody said that they did.

This is something that happens frequently because we often train students to agree with things in print. Students get very much into the idea that you’re given something to read because it’s supposed to be good and so you’re supposed to agree with it. I really wanted to push them, especially at this level. This is called an intermediate class, but given the experience these students came in with, I felt it was more like an advanced level class. They should be using their own analytical abilities to say “Wait a minute! The Emperor has no clothes here.” In retrospect, I wonder if they had been asked to do that before. I think mostly they had just been given things that were good, and were expected to assimilate it. I really wanted them to get this idea that just because you see a critique in print doesn’t mean it’s right! You should fight with it!

I had to shift tactics. I said to them, “You’re all fantasy readers. What did these people say about the genre? Weren’t any of you angry? Didn’t any of you feel insulted? These are academics writing in a philosophy journal. How do you respond to these things they’re saying, categorizing all fantasy as coming from just two strains? That’s stupid, isn’t it? Their two strains are completely wrong.”

I wanted them to feel that they had a sense of being able to analyze and defend on their own, and particularly to be able to defend genre in general, and especially the genres they work in. MIT is one of the very few places in the academic world where it is okay to be a genre writer. At most schools genre is really put down. I wanted them to be able to look at this text that purports to be about fantasy and see that the authors have no idea.

I do think that came through. We ended up with an incredible discussion of what are the markers, and what are the boundaries of genres. I hope that through our discussion they at least got the idea that it’s okay to fight with things in print.