a) What are the (short-range ordered) structures and elastic moduli of E-glass (aluminum-barium borosilicate glass) and silica glass in the bulk form?

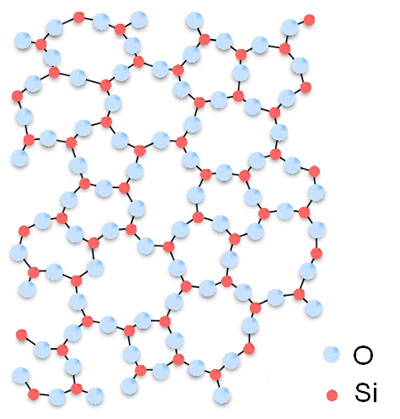

Silica (SiO2) glass is amorphous. This means that there is no long-range order, but there is a short-range order. This local ordering consists of a tetrahedral arrangement of O and Si atoms (see Fig. [1]).

E glass still consists for >50% of SiO2. SiO2 and B2O3 are the predominant network formers. BaO acts as a network modifier and Al2O3 is a glass network intermediate, which together with BaO has the capacity to form a network [2]. Just as for silica, there is no long-range order in E glass, which makes it an amorphous material. The specific short-range order in E glass will depend on its constituent atoms.

As for the elastic moduli, for SiO2 we find E = 72 GPa [3] and for E glass we find E = 80 GPa [4].

b) Would you expect the stiffness of these two types of glass to change as the physical dimensions were reduced to the diameters typical of current (2008) fiber optic applications? How about for nanoscale fibers? Why or why not? See also [3].

Image removed due to copyright restrictions. Please see Fig. 3 in [3].

According to Silva, et al. [3], the stiffness of silica does not depend on the physical dimensions for diameters above 280 nm. The core of single-mode optical fibers used for near-infrared applications such as telecommunications is typically >5 μm. This is safely above the 280 nm limit. As for nanoscale fibers, Dikin, et al. [5] report a substantial but unexplained decrease of the Young’s elastic modulus E below 100 nm. Around diameter of the order of 10 nm, Silva, et al. [3] report that the Young’s modulus increases again. This elastic stiffening can be understood on the basis of surface-constrained elasticity. Tensile stresses generated at the material surface contract the wire and increase the stiffness of the core material within the wire, due to nonlinear elasticity effects. Overall, there is an increase of 30% in stiffness as the diameter decreases from 100 nm to 10 nm due to the increased surface-area-to-volume ratio of the network solid.

c) State the Cij matrix you feel best captures the elastic constants of these glasses, and justify your answer in terms of the material structure.

Amorphous materials, having no long range structure, are inherently isotropic. The shape of an isotropic the Cij matrix is found on page 141 of “Physical Properties of Materials,” J. F. Nye [6].

d) Kurkjian, et al. [7] noted that Sakaguchi [8] had intentionally added dust particles to increase the failure stress of such glass fibers. What would the impact on isotropic elastic properties be for the fibers Sakaguchi created, for the sizes and volume fractions of particles he used?

According to Chapter 6 in Courtney [9], the elastic modulus Ec of a two-phase (glass matrix + dust particles) composite lies between the values of two extreme cases: a laminar stack of two materials alternating each other, with the force applied in the direction of the stacking on the one hand, and the same composite but with the force applied orthogonal to the stacking direction on the other hand.

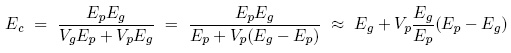

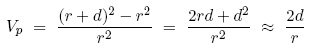

In the first case, each layer in the stack experiences an equal stress, and the elastic modulus Ec is calculated to be (Courtney 6.8):

with index g for the glass matrix and p for the dust particles. The last step is a Taylor expansion for the case that Vp << 1.

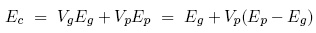

In the second case, each layer in the stack experiences an equal strain, and the elastic modulus is found to be (Courtney 6.12):

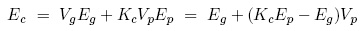

When Sakaguchi introduces dust particles with Ep > Eg, such as alumina (E[Al2O3]= 300 Gpa) or carbon (E[SiC]= 420 GPa), both of the cases predict an increase of the Young’s modulus of the glass fibers. The real value of Ec, which lies in between the two extrema, will thus also increase upon introduction of dust particles. This real value is sometimes described by an empirical relationship (Courtney 6.13):

where Kc < 1 is empirically determined.

To find a numerical value for the elastic modulus Ec, we first need to estimate the volume fraction Vp. In the most simple approximation, we can imagine the dust particles of diameter d to make up a mono-atomic shell of thickness d around the fiber of radius r. This corresponds in fact to the equal strain case described above. The volume fraction Vp is then given by the ratio of the cross-sectional area of the shell to the area of the fiber:

where the last approximation is valid for d << r. For the diameter of the silica fiber, we can use the value of 2*r = 125 μm mentioned in the article by do Nascimento [10].

For the alumina dust particles of d = 0.03 μm, 0.3 μm and 1 μm, the approximation d << r is valid and we find:

d = 0.03 μm → Vp = 0.00096 → Ec = 72.22 GPa = 1.003*Eg

d = 0.3 μm → Vp = 0.0096 → Ec = 74.2 GPa = 1.030*Eg

d = 1 μm → Vp = 0.032 → Ec = 79.4 GPa = 1.102*Eg

For the carbon dust particles of d = 20 μm (we don’t use the approximation d << r), we find: VP = 0.74 ≥ Ec = 330.4 GPa = 4.6*Eg. Note the increase by a factor ~5 in this simplified model!

We can elaborate on the validity of our assumption that the dust particles form a shell of thickness d around the fiber. In reality, the dust particles “surface density” may be not high enough to consider the dust particles as a dense shell around the fiber. A surface density factor in the expression for Vp can account for this. Also, we cannot use the equal strain expression (Kc = 1) anymore, but we have to work with a value for Kc < 1.

References

[1] Wikimedia Commons.

[2] Composition for Ceramic Substrate and Ceramic Circuit Component.

[3] Silva, Emilio C. C. M., et al. “Size Effects on the Stiffness of Silica Nanowires.” Small 2 (2006): 239-243.

[5] Dikin, D. A., et al. “Resonance Vibration of Amorphous SiO2 Nanowires Driven by Mechanical or Electrical Field Excitation.” Journal of Applied Physics 93 (2003): 226-230.

[6] Nye, J. F. Physical Properties of Crystals. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1985.

[7] Kurkjian, C. R., J. T. Krause, and M. J. Matthewson. “Strength and Fatigue of Silica Optical Fibers.” Journal of Lightwave Technology 7 (1989): 1360-1370.

[8] Sakaguchi, Shigeki, and Yoshinori Hibino. “Fatigue in Low-strength Silica Optical Fibers.” Journal of Materials Science 19 (October 1984): 3416-3420.

[9] Courtney. Mechanical Behavior of Materials. 2nd ed. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press Inc., 2005. ISBN: 9781577664253.

[10] Mauro do Nascimento, Eduardo, and Carlos Mauricio Lepienski. “Mechanical Properties of Optical Glass Fibers Damaged by Nanoindentation and Water Ageing.” Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 352 (September 15, 2006): 3556-3560.

Plasticity and fracture of microelectronic thin films/lines

Effects of multidimensional defects on III-V semiconductor mechanics

Defect nucleation in crystalline metals

Role of water in accelerated fracture of fiber optic glass | Problem Set 2 | Problem Set 3 | Problem Set 5

Carbon nanotube mechanics

Superelastic and superplastic alloys

Mechanical behavior of a virus

Effects of radiation on mechanical behavior of crystalline materials