(b) Are the superelastic alloys you’ve read about here subject to creep failure in tension? Think especially about paper 2 [13] and graph a rough (but justified) deformation mechanism map for one particular superelastic alloy of your choice.

In shape memory technology, namely NiTi, creep properties are generally not considered as being very important and have therefore received only limited attention in the literature. This is why, for example, vibrational strings constructed from NiTi wire are replacing conventional steel guitar and piano strings-they are found to hold a more constant pitch over long periods of time. Conventional steel wires drift down in frequency over time because of gradual material creep and/or because of plastic strain or stretch in response to temperature and humidity fluctuations. Because of the unique ability of NiTi wire to elastically recover large amounts of strain, vibratory strings constructed of NiTi wire are significantly less susceptible to such effects.

Some creep studies exist on the creep properties of NiTi, as reviewed and summarized below [6] :

Table 1. Summary of prior and present studies. Courtesy Elsevier, Inc., Science Direct. Used with permission. [6]

| INVESTIGATION | YEAR | SAMPLE DIAMETER (mm) | Ni (at.%) | PROCESSING |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mukherjee [1] | 1968 | 6.35 | 50.6 | Hot-swaged rod, annealed at 1000 °C |

| Kato, et al. [2] | 1999 | 0.9 | 49.5, 50, 50.5 | Drawn wires, annealed at 900 °C |

| Eggeler, et al. [3] | 2002 | 13 | 50.7 | Rods, solutionized at 850 °C, precipitation and coarsening during creep |

| Kobus, et al. [4] | 2002 | - | 50.7 | Annealed at 500-560 °C |

| Lexcellent, et al. [5] | 2005 | 18.5 | 50.0 | Hot drawn bars |

| Oppenheimer, et al. [6] | 2007 | 12.7 | 50.8 | Bars, annealed at 950-1100 °C |

Table 2. Summary of creep conditions and creep parameters measured in prior and present studies. Courtesy Elsevier, Inc., Science Direct. Used with permission. [6]

| MATERIAL | TEMPERATURE (°C) | STRAIN RATE (s-1) | Stress (MPa) | n | Q (kJ mol-1) | GRAIN SIZE (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mukherjee [1] | 700-1000 | 6 X 10-5—6 X 10-3 | 6-178 | 3 ± 0.2 | 251 ± 13 | - |

| Kato, et al. [2] | 628-888 | 1 X 10-5—2 X 10-2 | 11-81 |

1 and 5.9 (2.5 ± 0.2a) |

230-253 | 15 |

| Eggeler, et al. [3] | 470-530 | 2 X 10-9—8 X 10-6 | 90-150 | 2 | 334 | 35 |

| Kobus, et al. [4] | 500-560 | 2 X 10-7—3 X 10-5 | 120-180 | 5 | 421 | - |

| Lexcellent, et al. [5] | 597-897 | 3 X 10-3—4 X 10-2 | 10-35 | 3 | 222 ± 30 | - |

| Oppenheimer, et al. [6] | 950-1100 | 1 X 10-6—1 X 10-5 | 4.7-11 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 155 ± 14 | 48-140 |

a Single sample method.

In 1968, Mukherjee [1] was the first to study the creep properties of NiTi. The tensile flow stress was measured over six temperatures spanning 700-1000 °C (corresponding to homologous temperatures of 0.61-0.80, using the melting point of 1310 °C for equiatomic NiTi) at three constant strain rates spanning two orders of magnitude. The stress exponent and activation energy for creep were discussed in the light of the then-recent theories of viscous creep. Three decades later, Kato, et al. [2] published an extensive study of tensile creep in NiTi wires between 628 and 888 °C. Both constant creep rate and constant load experiments were performed. The creep exponent was determined using two different methods: first by performing strain rate jumps and measuring flow stress, and second by using the reduction in gauge area occurring during deformation to access many different stresses in a single constant load experiment. The former, more standard method gave a stress exponent more than twice that of the latter method. Eggeler and co-workers [3] and [4] published two studies where tensile creep was measured at lower temperatures (470-560 °C), at which Ti3Ni4 precipitates formed during heating to the test temperature and coarsened during creep testing. The evolving microstructure resulted in two sets of results: an initial minimum creep rate which was up to two orders of magnitude slower than the subsequent plateau (steady-state) creep rates. The respective stress exponents and activation energies were also different. These authors studied the dislocation structure developed after creep deformation, and the effect of prior creep upon the phase-transformation of NiTi near ambient temperature. Finally, in a recent study, Lexcellent, et al. [5] measured the creep rate of NiTi between 600 and 900 °C and obtained an activation energy higher than the tracer diffusivity activation energy of Ni in NiTi.

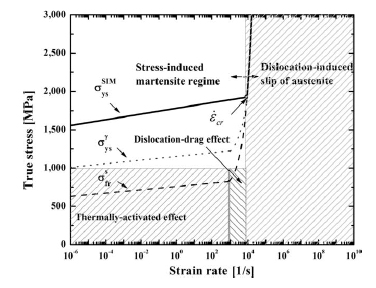

Nasser and Choi constructed a schematic deformation mechanism map of Ni-Ti-Cr alloy based on an experimental analysis of its creep behavior [7]. This empirical construct, which plots true stress as a function of strain rate, rather than normalized stress and normalized temperature, is reproduced below.

Courtesy Elsevier, Inc., Science Direct. Used with permission. [7]

(c) Compare the fracture strengths of superelastic alloys of your choice to those of the alloy components. For example, compare the fracture strength (in terms of fracture stress and plane strain fracture toughness) of Ni and Ti for the NiTi alloy. Discuss implications.

Fracture strength is the true normal stress on the minimum cross-sectional area at the beginning of fracture. In a tensile test, it is the load at fracture divided by the cross-sectional area of the specimen. This can be treated as an ultimate tensile strength. We can compare the fracture strength of the superelastic alloy NiTi to that of its components, Ni and Ti:

Ti:

Ni:

NiTi:

(Source: [8])

NiTi has a fracture strength nearly three times that of its strongest constituent, nickel! Thus, NiTi, unlike pure nickel or titanium, can be used in a variety of environments where high strength is requisite. This is the defining feature of alloys; alloying one metal with others often enhances its properties. Though the physical properties, like density, reactivity, Young’s modulus, and electrical and thermal conductivity, of an alloy may not diverge greatly from those of its elements, its engineering properties, such as tensile strength and shear strength may be substantially different from those of its constituent materials.

Fracture toughness is a property which describes the ability of a material containing a crack to resist fracture. It is one of the most important properties of any material for virtually all design applications. It is denoted by KIC and has the units of MPa√m . The subscript ‘IC’ denotes Mode I crack opening under a normal tensile stress perpendicular to the crack, since the material can be made thick enough to resist shear (Mode II) or tear (Mode III).

Fracture toughness is a quantitative way of expressing a material’s resistance to brittle fracture when a crack is present. If a material has a large value of fracture toughness it will probably undergo ductile fracture. Brittle fracture is very characteristic of materials with a low fracture toughness value.

Fracture mechanics, which leads to the concept of fracture toughness, was largely based on the work of A. A. Griffith who, among other things, studied the behavior of cracks in brittle materials. Below is a table of plane strain fracture toughnesses for several representative materials (adapted from [9]).

| MATERIAL | KIC(MPa√m) |

|---|---|

| Metals | |

|

Aluminum alloy |

36 |

|

Steel alloy |

50 |

|

Titanium alloy |

44-66 |

| Aluminum | 14-28 |

| Ceramics | |

| Aluminum oxide | 3-5 |

|

Silicon carbide |

3-5 |

| Soda-lime-glass | 0.7-0.8 |

|

Concrete |

0.2-1.4 |

| Polymers | |

|

Polymethyl methacrylate |

1 |

|

Polystyrene |

0.8-1.1 |

Very little data is reported for the fracture toughness of NiTi. He, et al., [10] in a study on the hydrogen effects on NiTi, have recently reported the KIC values for austenitic NiTi (Ni/Ti ratio of 55/45 and an austenite start temperature of 80°C) at 20°C. They used tensile testing and x-ray diffraction to confirm the formation of stress-induced martensite. They report KIC = 39.2 MPa√m for samples that were annealed at 150°C, and 53.1 MPa√m for samples that were annealed at 700°C for half an hour.

The fracture toughness of NiTi is not exceptionally high, particularly when compared to other commonly used biomedical materials such as 316SS. Furthermore, what’s interesting is that Ni alloys and Ti alloys, exclusive of the shape memory alloys, have fracture toughnesses ranging from 50-150 MPa√m (Ashby Chart of Fracture Toughness versus Fracture Strength). Nitinol is at the lower end of this range. Pure Ni and Ti have plane strain fracture toughnesses of 100-150 MPa√m and 50-70 MPa√m, respectively [8].

Therefore, we can conclude that a superelastic alloy’s fracture toughness is much higher than that of its alloy components. Fracture toughness KC is related to the material toughness GC via  in plane strain conditions; GC is the energy density beneath the entire stress-strain curve. Thus, a material that is ductile and has a high ultimate strength generally also has high material toughness, and subsequently high fracture toughness.

in plane strain conditions; GC is the energy density beneath the entire stress-strain curve. Thus, a material that is ductile and has a high ultimate strength generally also has high material toughness, and subsequently high fracture toughness.

However, the fracture mechanism of a superelastic alloy is not as simple to intuit. Articles which present studies of fatigue-crack propagation behavior in Nitinol, a 50Ni-50Ti (atomic percent) superelastic/shape-memory alloy, with particular emphasis on the effect of the stress-induced martensitic transformation on crack-growth resistance, present that in general, fatigue-crack growth resistance was found to increase with decreasing temperature, such that fatigue thresholds were higher and crack-growth rates slower in martensite compared to stable austenite and superelastic austenite. Of note was the observation that the stress-induced transformation of the superelastic austenite structure, which occurs readily at 37 °C during uniaxial tensile testing, could be suppressed during fatigue-crack propagation by the tensile hydrostatic stress state ahead of a crack tip in plane strain; this effect, however, was not seen in thinner specimens, where the constraint was relaxed due to prevailing plane-stress conditions. [12]

References

[1] Mukherjee, A.K. “High-Temperature-Creep Mechanism of TiNi.” Journal of Applied Physics 39 (1968): 2201-2204.

[2] Kato, H., T. Yamamoto, S. Hashimoto, and S. Miura. “High-Temperature Plasticity of the β-phase in Nearly-Equiatomic Nickel-Titanium Alloys.” Materials Transactions of the JIM 40 (1999): 343-350.

[3] Eggeler, G., J. Khalil-Allafi, K. Neuking, and A. Dlouhy. “Creep of Binary Ni-rich NiTi Shape Memory Alloys and the Influence of Pre-creep on Martensitic Transformations.” Zeitschrift für Metallkunde 93 (2002): 654-660.

[4] Kobus, E., K. Neuking, and G. Eggeler. “The Creep Behavior of a NiTi-Alloy and the Effect of Creep Deformation on its Shape-Memory Properties.” Praktische Metallographie - Practical Metallography 39 (2002): 177.

[5] Lexcellent, C., P. Robinet, J. Bernardini, D. L. Beke, and P. Olier. “High Temperature Creep Measurements in Equiatomic Ni-Ti Shape Memory Alloy.” Materialwissenschaft und Werkstofftechnik 36 (2005): 509-512.

[6] Oppenheimer, Scott M., Andrea R. Yung, and David C. Dunand. “Power-law Creep in Near-equiatomic Nickel-titanium Alloys.” Scripta Materialia 57 (2007): 377-380.

[7] Nemat-Nasser, S., and Choi, Jeom Yong. “Strain Rate Dependence of Deformation Mechanisms in a Ni-Ti-Cr Shape-memory Alloy.” Acta Materialia 53 (January 2005): 449-454.

[8] MatWeb, material property database.

[9] Wikipedia.

[10] He, J. Y., et al. “The Role of Hydride, Martensite, and Atomic Hydrogen in Hydrogen-induced Delayed Fracture of TiNi Alloy.” Materials Science and Engineering A 364 (January 15, 2004): 333-338.

[11] Courtney. Mechanical Behavior of Materials. 2nd ed. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press Inc., 2005. ISBN: 9781577664253.

[12] McKelvey, A. L., and R. O. Ritchie. “Fatigue-crack Propagation in Nitinol, a Shape-memory and Superelastic Endovascular Stent Material.” Journal of Biomedical Materials Research A 47 (December 5, 1999): 301-308.

[13] Taillard, K., et al. “Phase Transformation Yield Surface of Anisotropic Shape Memory Alloys.” Materials Science and Engineering A 438-440 (2006): 436-440.

Plasticity and fracture of microelectronic thin films/lines

Effects of multidimensional defects on III-V semiconductor mechanics

Defect nucleation in crystalline metals

Role of water in accelerated fracture of fiber optic glass

Carbon nanotube mechanics

Superelastic and superplastic alloys | Problem Set 2 | Problem Set 3 | Problem Set 5

Mechanical behavior of a virus

Effects of radiation on mechanical behavior of crystalline materials