(b) One of the cool things about a virus is that after the prohead shoots in the genetic material into the host cell (say, a bacterium), the genetic material is replicated until there is so much pressure that the host cell fractures. Assuming this is an E. coli bacterium with an initial crack size equal to the width of the prohead, find the Griffith fracture strength of the E. coli. You’ll have to assume some properties to do this, so cite and justify these.

Assumptions (from literature):

Computation:

σ = (2Eγ/πa)(1/2) = 13.8 MPa

(c) Ivanovska, et al. [1] says the virus capsids are tough, but we said in class that this is the strain energy density up to the point of fracture. Assuming the fracture strength of a virus is 3 times the computed yield strength from PS3, and that the virus deforms in a linear elastic-linear strain hardening plastic mode up to the point of fracture, compute the toughness UT. Discussion on p. 7604 of their paper is also helpful.

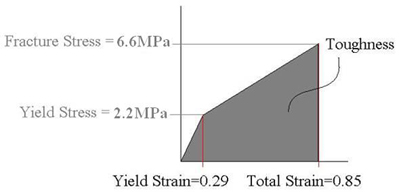

From PS3 we calculated the yield stress to be 2.2 MPA and thus we can assume the fracture stress to be 3 times this value or 6.6 MPA.

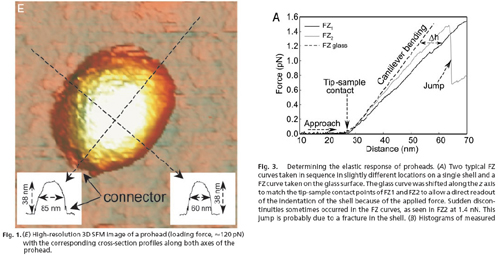

From the following figures, taken from Ivanovska, et al., we see that the prohead dimension along the axis of stress/strain is 38 nm (Fig. 1). From Fig. 3, we see that the total strain distance the AFM tip moved from contact to fracture to be 62 nm - 29 nm = 33 nm. Thus the strain experienced by the prohead at fracture (rupture) is 33 nm/38 nm = .85.

Applying these values and the assumption of linear elastic and linear strain hardening we get a stress/strain curve as shown below.

Courtesy of National Academy of Sciences, USA. Used with permission.

Source: Ivanovska, I. L., P. J. Pablo, B. Ibarra, G. Sgalari, F. C. MacKintosh, J. L. Carrascosa, C. F. Schmidt, and G. J. L. Wuite. “Bacteriophage capsids: Tough nanoshells with complex elastic properties.” PNAS 101 (2004): 7600-7605. Copyright 2004 National Academy of Sciences, USA.

The toughness can be computed from the figure below by finding the area under the stress/strain curve.

1/2*.29*2.2 MPa + (.85 - .29)2.2 MPa + 1/2(.85 - .29)(6.6 MPa - 2.2 MPa) = 2.783 MPa

References

[1] Ivanovska, I. L., P. J. Pablo, B. Ibarra, G. Sgalari, F. C. MacKintosh, J. L. Carrascosa, C. F. Schmidt, and G. J. L. Wuite. “Bacteriophage Capsids: Tough Nanoshells with Complex Elastic Properties.” PNAS 101 (2004): 7600-7605.

[2] Ramos, Daniel, et al. “Measurement of the Mass and Rigidity of Adsorbates on a Microcantilever Sensor.” Sensors 7 (2007): 1834-1845.

[3] Yao, X., et al. “Thickness and Elasticity of Gram-Negative Murein Sacculi Measured by Atomic Force Microscopy.” Journal of Bacteriology 181 (November 1999): 6865-6875.

[4] Lopez-Montero, Ivan, et al. “High Fluidity and Soft Elasticity of the Inner Membrane of Escherischia coli Revealed by the Surface Rheology of Model Langmuir Monolayers.” Langmuir 24 (2008): 4065-4076.

[5] van Oss, C. J., A. Docoslis, and R. F. Giese. “Role of the Water-air Interface in Determining the Surface Tension of Aqueous Solutions of Sugars, Polysaccharides, Proteins, and Surfactants.” Contact Angle, Wettability, and Adhesion 2 (2002): 3-12.

Plasticity and fracture of microelectronic thin films/lines

Effects of multidimensional defects on III-V semiconductor mechanics

Defect nucleation in crystalline metals

Role of water in accelerated fracture of fiber optic glass

Carbon nanotube mechanics

Superelastic and superplastic alloys

Mechanical behavior of a virus | Problem Set 2 | Problem Set 3Problem Set 3 | Problem Set 5

Effects of radiation on mechanical behavior of crystalline materials