Group Members

- Agustin Mohedas

- Kevin Huang

- Heechul Park

- Jing Shan

References

Zandi, R., and D. Reguera. “Mechanical Properties of Viral Capsids.” Physical Review E 72 (2005): 021917.

Ivanovska, I. L., P. J. Pablo, B. Ibarra, G. Sgalari, F. C. MacKintosh, J. L. Carrascosa, C. F. Schmidt, and G. J. L. Wuite. “Bacteriophage Capsids: Tough Nanoshells with Complex Elastic Properties.” PNAS 101 (2004): 7600-7605.

Buenemann, M., and P. Lenz. “Mechanical Limits of Viral Capsids.” PNAS 104 (2007): 9925-9930.

Wiki Assignments

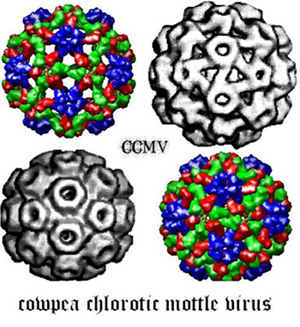

(b) Zandi, et al. note that virus capsid behavior can be considered as a competition between bending and strain energies at the continuum level. State the magnitude of these two mechanical energy components on a flat plate of thickness equal to the viral capsid wall, of width and length equal to the CCMV capsid facet, and under a state of hydrostatic stress (pressure) plus a superposed normal point load at the center of the capsid facet.

(c) The authors rely on a thermodynamic definition of stresses and a Lennard-Jones inter-capsomer potential to predict the dependence of stress on capsid size. State their definition of the LJ potential in terms of the symbols we used in class, and explain why the radial and tangential stresses they compute from this potential (under the defined stress state) monotonically decrease with increasing capsid radius.

(d) Briefly summarize the implications of this trend in terms of virus behavior.

(b) Considering Ivanovska, et al.’s Fig. 1E rendering of a bacteriophage prohead “shell”, compute the stress required to initiate plastic deformation if the prohead were considered to be a short cylindrical shell under uniaxial compression.

(c) These authors state that imaging of the proheads in contact mode atomic force microscopy (AFM) allows for the study of prohead deformation under “uniaxial pressure.” This is incorrect at several levels. Develop a brief, justified objection to this claim, considering the design of the experiment in detail.

(d) These authors also claim that the mechanical testing of such proheads enables prediction of the elastic properties of the bacteriophage, by recourse to nonlinear elastic bucking of shells. Based on the data they present in this paper and known continuum mechanical analysis of shell elasticity, is this claim justified? Timoshenko is an excellent resource on mechanical analysis of shells.

(b) One of the cool things about a virus is that after the prohead shoots in the genetic material into the host cell (say, a bacterium), the genetic material is replicated until there is so much pressure that the host cell fractures. Assuming this is an E. coli bacterium with an initial crack size equal to the width of the prohead, find the Griffith fracture strength of the E. coli. You’ll have to assume some properties to do this, so cite and justify these.

(c) Ivanovska, et al. says the virus capsids are tough, but we said in class that this is the strain energy density up to the point of fracture. Assuming the fracture strength of a virus is 3 times the computed yield strength from PS3, and that the virus deforms in a linear elastic-linear strain hardening plastic mode up to the point of fracture, compute the toughness UT . Discussion on p. 7604 of their paper is also helpful.

Final Presentation

“Mechanical Behavior of a Virus.” (PDF)

Plasticity and fracture of microelectronic thin films/lines

Effects of multidimensional defects on III-V semiconductor mechanics

Defect nucleation in crystalline metals

Role of water in accelerated fracture of fiber optic glass

Carbon nanotube mechanics

Superelastic and superplastic alloys

Mechanical behavior of a virus | Problem Set 2 | Problem Set 3Problem Set 3 | Problem Set 5

Effects of radiation on mechanical behavior of crystalline materials