Eclipse and Emergence

Involving Arthur Eddington’s eclipse expedition to test Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity

(Public domain image)

Length: 8-10 double-spaced pages. You should use standard margins (1-inch to 1.25-inches on each side of the page), and a 12-point font.

Grade: Your grade on the Final Paper will contribute 35% of your final course grade.

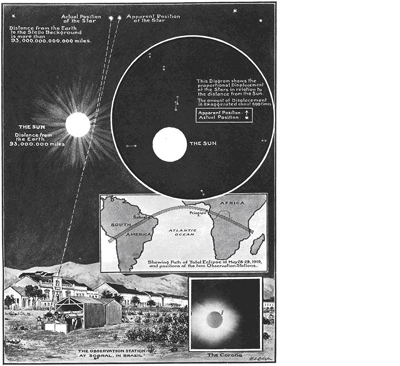

Surely one of the most important events in the history of the universe—at least since humans began walking upright—is the development of Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity. Einstei’s theory, and Einstein himself, became worldwide celebrities in November 1919: that was the month in which Arthur Eddington announced that his astronomical expedition had measured the bending of starlight as it passed near the sun during a total eclipse, and found quantitative agreement with Einstein’s prediction. When Einstein traveled to the United States soon after that, he was greeted with ticker-tape parades. Eddington’s eclipse-expedition results—announced to great fanfare just one year after the end of World War I—seemed to settle the scientific score decisively: Einstein’s theory of gravity was in, Newton’s was out.

What, then, are we to make of comments such as this:“Eddington evaluated his [observational] results according to how they conformed to his preferred theoretical predictions. On one hand, inordinate value was attached to photographs that approximated Einstein’s 1.7 seconds of arc deflection; on the other, dubious ad hoc reasons were invented for jettisoning any that disagreed.” In short, this argument goes, Eddington “manipulated” and “massaged” his data to produce the answer he was looking for.1 Take away those heavy-handed interventions, it has been suggested, and one of the earliest and most important confirmations of Einstein’s theory falls apart. No data massage, no ticker-tape parade.

Scientists, historians, philosophers, and sociologists continue to debate Eddington’s activities surrounding the famous eclipse expedition—from his motivations to undertake the experiment, to his presentation of the scientific stakes before, during, and after the experiment, to his handling of specific instruments and data during his analysis. Based on your reading of several primary and secondary sources, articulate and defend your own argument about Eddington and the eclipse expedition. Was this a case of scientific fraud? Savvy public relations? Wishful thinking? Science as usual?

Your paper must include at least two primary sources and at least four secondary sources. Some relevant sources you might wish to consider are listed below. Your sources need not be limited to these. A primary source is material produced at the time in question by one of the participants in the events under study. A secondary source is material produced by a later analyst (scientist, historian, journalist, etc.) that attempts to interpret the primary sources, perhaps in terms of broader context or wider historical tradition.

You are strongly encouraged to work with your Teaching Assistant while preparing your final project. Naturally if you have additional questions you may also consult with Professors Jones and Kaiser.

In the written portion of this assignment, you should use standard footnote conventions, giving full bibliographic information for all sources from which you draw, and include a bibliography at the end. Examples of appropriate footnote and bibliography formats appear in the handout “Footnotes, Bibliographies, and the Good Life” referenced for previous papers. You should also consult our “Guidelines for Writing Papers” both for tips on how to organize your essay and for information regarding proper use of web-based sources. Failure to use appropriate footnote and bibliography formatting will lower your grade. If you have any questions about how to cite your sources, please check with any of the instructors.

Primary Sources

Fowler, A. (chair). “Meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society.” The Observatory 42 (July 1919): 261-262. (PDF)

Thomson, J. J. (chair). “Joint Meeting of the Royal Society and the Royal Astronomical Society.” The Observatory 42 (November 1919): 389-398. (PDF)

Dyson, F. W., A. S. Eddington, and C. Davidson. “A Determination of the Deflection of Light by the Sun’s Gravitational Field, from Observations Made at the Total Eclipse of May 29, 1919.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 220A (1920): 291-333. (PDF)

Harvey, G. M. “Gravitational Deflection of Light: A Re-examination of the Observations of the Solar Eclipse of 1919.” The Observatory 99 (December 1979): 195-198.

Secondary Sources

Earman, John and Clark Glymour. “Relativity and Eclipses: The British Eclipse Expeditions of 1919 and their Predecessors.” Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences 11 (1980): 49-85.

Collins, Harry, and Trevor Pinch. “Two Experiments that ‘Proved’ the Theory of Relativity.” In The Golem: What Everyone Should Know About Science. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993, 27-55. [Preview with Google Books]

Waller, John. “The Eclipse of Isaac Newton: Arthur Eddington’s ‘Proof’ of General Relativity.” In Einstein’s Luck: The Truth Behind Some of the Greatest Scientific Discoveries. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002, 49-63. ISBN: 9780192805676.

Sponsel, Alistair. “Constructing a ‘Revolution in Science’: The Campaign to Promote a Favourable Reception for the 1919 Solar Eclipse Experiments.” British Journal for the History of Science 35 (2002): 439-467.

Stanley, Matthew. “An Expedition to Heal the Wounds of War: The 1919 Eclipse Expedition and Eddington as Quaker Adventurer.” Isis 94 (2003): 57-89.

Almassi, Ben. “Trust in Expert Testimony: Eddington’s 1919 Eclipse Expedition and the British Response to General Relativity.” Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 40 (2009): 57-67.

Kennefick, Daniel. “Testing Relativity From the 1919 Eclipse—A Question of Bias.” Physics Today, March 2009, 37-42.

Sample Student Work

“A Study Eclipsed by Confirmation Bias” by MIT student (PDF) (Courtesy of MIT student. Used with permission.)

1 Waller, John. Einstein’s Luck: The Truth Behind Some of the Greatest Scientific Discoveries. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002, 58. ISBN: 9780192805676.