In the Flesh

Involving Gunther von Hagens’s controversial exhibition, Body Worlds

(Public domain image)

Length: 8-10 double-spaced pages. You should use standard margins (1-inch to 1.25-inches on each side of the page), and a 12-point font.

Grade: Your grade on the Final Paper will contribute 35% of your final course grade.

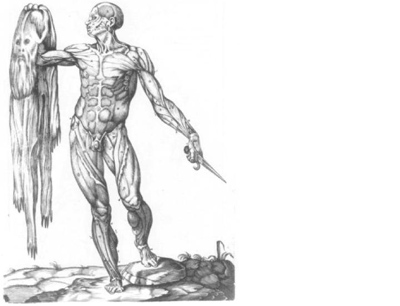

Body Worlds: The Anatomical Exhibition of Real Human Bodies is an exhibition of “plastinated” human bodies, composed by the German anatomist Gunther von Hagens. Hagens creates his specimens using a technique he invented in 1977 for turning human body parts into plastic. Many of you may have seen Body Worlds in one of its many incarnations. If you have not seen it “in the flesh,” you have probably seen the newspaper ads, billboards or placement as scenery in James Bond movies. Since it first opened in 1995 in Tokyo, between twenty-five and thirty million people have attended Body Worlds: The Anatomical Exhibition of Real Human Bodies. The exhibition traveled to England in 2002, where it first encountered major criticisms on scientific, ethical, and aesthetic grounds. It has since traveled all over Europe, Asia, and North America, along with the advertising billboards with catchy slogans. For documentation see www.bodyworlds.com.

The Boston Museum of Science, for example, hosted Body Worlds: The Anatomical Exhibition of Real Human Bodies from 2006 to 2007, and the city was ablaze with ads the whole time. In the show, “real” human specimens, including whole-body plastinates, individual organs, organ configurations, and transparent body slices are arranged in gigantic exhibition halls; at the exit, visitors are requested to donate their bodies, post-mortem, to the project. In Boston, as throughout the world, the show met with huge successes and also huge controversies. Is this science or spectacle? Is this pedagogically useful or morally suspect?

This assignment asks you to develop an argument that situates Body Worlds, and the legal, ethical, and scientific controversies surrounding it, in historical context. In developing your argument, consider the histories of the scientific disciplines of anatomy and physiology, and of material practices – such as vivisection and dissection – that have long constituted part of both scientific research and scientific education. Finally, consider the historical context of science, culture, and spectacle – as in the case of the public dissections of 16th-century Padua, the incredible popularity of Vesalius’ volume, and the controversy over grave-robbing. These are only suggestions for relevant examples from history—feel free to pick your own historical examples as you see fit.

Sources pertaining to the contemporary context include primary sources by Gunther von Hagens, early reviewers of the exhibit, and the official Body Worlds Web site. Secondary sources include articles by ethicists and historians of science. Sources pertaining to the historical context include primary sources by Andreas Vesalius and William Harvey, as well as secondary sources by historians of biology and medicine. You should include a mixture of types of sources in your research and this range of sources should be reflected in the citations you include in your final paper. Note: Your paper must include at least two primary sources and at least four secondary sources.

You are strongly encouraged to work with your Teaching Assistant while preparing your final project. Naturally if you have additional questions you may also consult with Professors Jones and Kaiser.

In the written portion of this assignment, you should use standard footnote conventions, giving full bibliographic information for all sources from which you draw, and include a bibliography at the end. Examples of appropriate footnote and bibliography formats appear in the handout “Footnotes, Bibliographies, and the Good Life” referenced for previous papers. You should also consult our “Guidelines for Writing Papers” both for tips on how to organize your essay and for information regarding proper use of web-based sources. Failure to use appropriate footnote and bibliography formatting will lower your grade. If you have any questions about how to cite your sources, please check with any of the instructors.

Primary Sources

Hagens, G. von. “Plastinated Specimens and Plastination.” and “On Gruesome Corpses, Gestalt Plastinates and Mandatory Interment.” In Body Worlds: The Anatomical Exhibition of Real Human Bodies. Edited by Gunther von Hagens, and Angelina Whalley, translated by Francis Kelly. Heidelberg: Institut für Plastination, 2004, pp. 20-37 and 260-282.

———. “No Skeletons in the Closet – Facts, Background and Conclusions: A Response to the Alleged Corpse Scandals in Novosibirsk, Russia, and Bishkek, Kyrgizstan, Associated with the Body Worlds Exhibition.” Public statement, distributed online 17 November 2003. (PDF).

Harvey, W. “Proeme and Introductory Chapters of De Motu Cordis” [1628]. In The Anatomical Exercises in English Translation. Dover, 1995, pp. 1-23. ISBN: 9780486688275.

Vesalius, A. “Preface to On the Fabric of the Human Body” and “Book 5: The Best Method for Conducting the Anatomy” [1543]. In Charles D. O’Malley, Andreas Vesalius of Brussels, 1514-64.University of California Press, 1964, pp. 317-324 and 342-360 [Preview with Google Books]

Vesalius, A., J. B. Saunders, and C. D. O’Malley “Title Pages to the 1st Edition of ‘De Humani Corporis Fabrica’, 1543, and 2nd edition, 1555. In Vesalius: The Illustrations from His Works. The World Publishing Company, 1950, pp. 42-45.

Secondary Sources

Allan, Anita L. “No Dignity in Body Worlds: A Silent Minority Speaks.” The American Journal of Bioethics 7, no. 4 (2007): 24-25.

Allchin, Douglas. ““Hands-off” Dissection? What Do We Seek in Alternatives to Examining Real Organisms?” The American Biology Teacher 67, no. 6 (2005): 369-374.

Burns, Lawrence. “Gunther Von Hagens’ BODY WORLDS: Selling Beautiful Education.” The American Journal of Bioethics 7, no. 4 (2007): 12–23.

Connor, J. T. H. “Exhibit Essay Review: ‘Faux Reality’ Show? The Body Worlds Phenomenon and Its Reinvention of Anatomical Spectacle.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 81 (2007): 848–865.

Herscovitch, Penny. “Rest in Plastic: Review of ‘Body Worlds, The Anatomical Exhibition of Real Human Bodies’ by Gunther von Hagens.” Science 299 (February 7, 2003): 828-829.

Park, Katharine. “The Criminal and the Saintly Body: Autopsy and Dissection in Renaissance Italy.” In The Renaissance: Italy and Abroad, Rewriting Histories. Edited by J. J. Martin. New York: Routledge, 2002, 224-252.9780415260626.

Porter, Roy. “The Body.” In Blood and Guts: A Short History of Medicine. W. W. Norton & Co., 2003, pp. 53-75. ISBN: 9780393325690.

Singh, Debashis. “Scientist or Showman?” British Medical Journal 326 (2003): 468.

Orla Smith, “Anatomy: The Art of the Oldest Science.” Science 299 (February 7, 2003): 829.

Walter, Tony. “Body Worlds: Clinical Detachment and Anatomical Awe.” Sociology of Health and Illness 26, no. 4 (2004): 464–488.

Sample Student Work

(Courtesy of the students and used with permission.)

“Controversy and the Human Body: Science and Spectacle in Body Worlds” by MIT student (PDF)

“Poking, Prodding, and Slicing: Anatomy as We Know It” by MIT student (PDF)

“Conflict: Conceptions of the Body” by MIT student (PDF)