(a) Explain the physical basis of superelasticity.

Superelasticity is an elastic response to a relatively high stress induced by a phase transformation between the austenitic and martensitic phases of a crystal. This phenomenon results from the reversible motion of domain boundaries during the phase transformation, rather than just bond stretching or the introduction of defects in the crystal lattice. Even if the domain boundaries do become pinned, they may be reversed through heating. Thus, a superelastic material may return to its previous shape (hence, shape memory) after the removal of even relatively high applied strains.

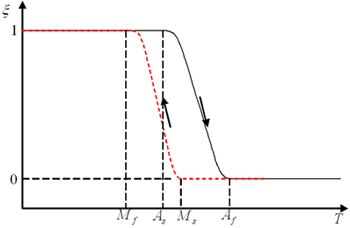

The Bain Correspondence involves the austenite/martensite phase transformation between a face centered crystal lattice and a body centered tetragonal crystal structure. The temperature-induced transformation is characterized by four temperatures: Ms and Mf during cooling and As and Af during heating. Ms and Mf refer to the temperatures at which transformation from the parent beta-phase into martensite starts and finishes, respectively. As*_and _A*f indicate the temperatures whereby the reverse transformation starts and finishes, respectively. The overall transformation describes a hysteresis on the order of 10°C to 50°C in temperature. For T >Af, the martensitic phase can also be caused by straining the sample. When deformed above Af, the deformation is fully reversible; for Ms < T < Af temperature. During straining, the stress at which transformation occurs is almost constant until the material is fully transformed. Further straining leads to elastic loading of the martensite, followed by plastic deformation. Reversible strains up to 8% are obtainable, versus the 0.2% of normal metals.

Indeed, the microstructural difference between martensite and austenite translates to a change in macroscopic behavior of the material. Martensite is a crystal structure that is formed by displacive transformation, as opposed to much slower diffusive transformations. It includes a class of hard minerals occurring as lathe- or plate-shaped crystal grains. When viewed in cross-section, the lenticular (lens-shaped) crystal grains appear acicular (needle-shaped).

Martensite has a different crystalline structure (tetragonal) than the face-centered-cubic austenite from which it is formed, but it shares identical chemical or alloy composition. The transition between these two structures requires very little thermal activation energy because it occurs by the subtle but rapid rearrangement of atomic positions, and has been known to occur even at cryogenic temperatures. Martensite is not shown in the equilibrium phase diagram of the iron-carbon system because it is a metastable phase, the kinetic product of rapid cooling of steel containing sufficient carbon. Too much martensite leaves steel brittle, whereas too little, leaves it soft.

It is important to differentiate between the one-way and two-way shape memory. With the one-way effect, cooling from high temperatures does not cause a macroscopic shape change. A deformation is necessary to create the low-temperature shape. On heating, transformation starts at As and is completed at Af (typically 2 to 20°C or hotter, depending on the alloy or the loading conditions). As is determined by the alloy type and composition. It can be varied between -150°C and 200°C. The two-way shape memory effect describes how the material remembers two different shapes, one at low temperatures, and one at the high temperature shape. This can also be obtained without the application of an external force (intrinsic two-way effect).

(b) You are asked to quantify the Young’s elastic modulus of a shape memory alloy such as Ni-Ti. Based on your understanding from the van Humbeeck review [1], how would you respond?

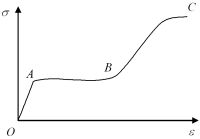

The Young’s modulus of shape memory alloy changes drastically during transformation. The exact behavior of an SMA upon loading is temperature and phase dependent. Normally, the stress versus strain relationship of an SMA at a given temperature can be divided into three regimes.

Point O to point A is elastic deformation, which might be not so apparent at around the martensite start temperature due to the V-shape phenomenon in the transformation start stress versus temperature relationship. Point A to point B is the regime dominated by the phase transformation and/or reorientation associated with a very large recoverable strain. Transformation front movement may be observed in this regime. Point B to point C is the hardening regime in which some further transformation occurs together with plastic deformation, in particular in the range close to fracture point C.

And the stress-strain curve which contains unloading is this.

Image removed due to copyright restrictions. Please see stress-strain curve.

That is, the Young’s modulus of SMAs is phase dependent. The difference of the Young’s modulus between austenite and martensite in SMAs can be significant. It can be as much as a few times in some SMAs. A difference by as much as a factor of four was reported in a polycrystalline NiTi. This is due to the lattice structure change in the phase transformation. In fact, even in the case of reorientation among martensite variants, because of the anisotropy of martensite variants, the modulus of elasticity is orientation dependent.

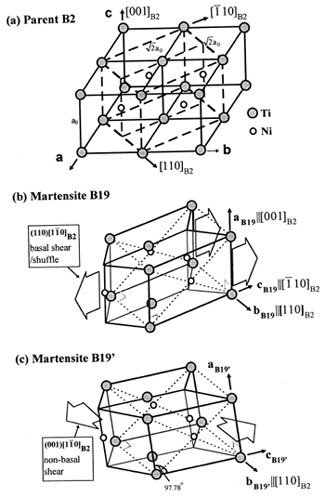

Here is the phase diagram of Ni-Ti, superelastic alloy and the crystal structure of martensite.

Image removed due to copyright restrictions. Please see phase diagram of Ni-Ti.

Courtesy Elsevier, Inc., Science Direct. Used with permission. [2]

It shows structure relationship among B2 parent phase and two kinds of martensite, B19 and B19’. (a) is the parent phase B2 structure with a FCT cell delineated. (b) is a orthorhombic martensite B19 formed by shear/shuffle of the basal plane. (c) is a monoclinic martensite B19’, which is viewed as a B19 structure sheared by a non-baral shear, the modulus of which corresponds to C44.

(c) How, then, do you explain the values of E and G in his Table 1 [1]?

The elastic constants E and G referenced in Van Humbeeck, Table 1, are labeled as being for austenite. The elastic constants represent the moduli of step 0-A of Figure 2. The author warns the reader that these material properties are approximate properties to be used for reference, but not to be used for design.

(d) What in terms of material structure and continuum level mechanical properties determines the maximum mechanical energy possible to obtain from a superelastic alloy in an actuator application?

Shape Memory Alloys (SMAs) can be used as thermal actuators by using the property that when they are in an undeformed shape at a temperature higher than Af, they can be cooled to a temperature below Mf to cause a reversible shape change. In this way, the materials do not actually generate energy, but rather store and release potential energy that is stored in the microstructure.

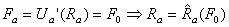

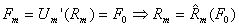

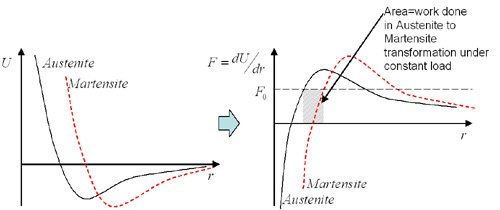

The straining due to temperature change occurs due to changes of crystalline arrangement of the metallic atoms. In the initial, undeformed state, the material is martensitic. As the material is cooled below the Mf temperature, material is converted into an austenitic state. The martensitic and austenitic states both have separate free energy potential functions (Um and Ua, respectively) because they describe different crystalline configurations. Given a constant externally-applied force per bond (F0), equilibrium distances can be found by differentiating the potentials with respect to interatomic distance, then solving for the interatomic distance corresponding to F0. The difference between the loaded equilibrium bond distance for martensite and austenite will indicate how much displacement is achieved by changing the temperature. This displacement times the externally-applied force will give the stored or returned mechanical energy. Mathematically, this can be seen as:

where

denotes the functional dependence of Ra on F rather than multiplication of the two. This process is demonstrated graphically in the figure below.

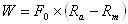

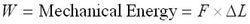

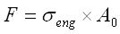

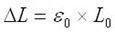

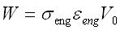

On the continuum level, the energy density can be calculated for a tension-loaded SMA wire by applying a constant stress to a wire and recording the strain variation as a function of temperature. Mechanical energy can be found as

Combining the above three equations gives:

Similar experiments have been done for a wire in tension, torsion, and bending, and they are summarized in the table below, after Humbeeck [1].

| LOAD CASE | ENERGETIC EFFICIENCY (1%) | ENERGY DENSITY (J/kg) |

|---|---|---|

| (Carnot) | 9.9 | – |

| Tension | 1.3 | 466 |

| Torsion | 0.23 | 82 |

| Bending | 0.013 | 4.6 |

Notice that there is a geometric effect in this table. This is due to the fact that not all of the wire is loaded to the full strain in the cases of torsion and bending.

References

[1] Van Humbeeck, J. “Shape Memory Alloys: A Material and a Technology.” Advanced Engineering Materials 3 (2001): 837-850.

[2] Otsuka, Kazuhiro, and Xiaobing Ren. “Recent Developments in the Research of Shape Memory Alloys.” Intermetallics 7 (1999): 511-528.

Plasticity and fracture of microelectronic thin films/lines

Effects of multidimensional defects on III-V semiconductor mechanics

Defect nucleation in crystalline metals

Role of water in accelerated fracture of fiber optic glass

Carbon nanotube mechanics

Superelastic and superplastic alloys | Problem Set 2 | Problem Set 3 | Problem Set 5

Mechanical behavior of a virus

Effects of radiation on mechanical behavior of crystalline materials