Course Meeting Times

Lectures: 1 session / week; 2 hours / session

Course Description

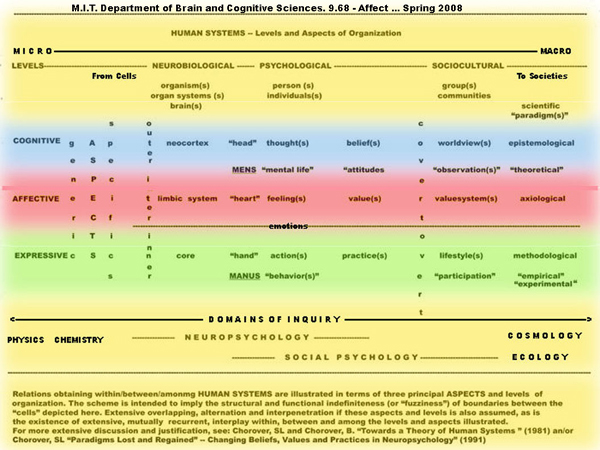

This course studies the relations of affect to cognition and behavior, feeling to thinking and acting, and values to beliefs and practices. These connections will be considered at the psychological level of organization and in terms of their neurobiological and sociocultural counterparts. In addition to weekly class sessions, students participate in small study groups that meet for two hours per week.

Topics

The syllabus contains, in a single document, a detailed description of the approach to 9.68 including information about the reading and writing assignments, the collaborative learning system, study groups and grading. (PDF)

- Introduction and Overview

- Conduct and Administration of Subject

- Students: Caveat Emptor

- Final grades

- Instructional subsystem

- Communication

- Being there: Attendance and participation

- Consider your attitudes

- Study groups

- First group meeting

- Developmental trajectories

- Formative evaluation

- Workload

- The MFA field trip

- Assignments

- Required text

- Additional Readings

- Viewing films

- Journal-keeping

- Keeping a timesheet

- Writing reaction papers

- Plagiarism

- Paper chase format

- What is collaborative learning?

- Planning/producing end-of-term project or paper

- Interim and final grades

- A final note about the 9.68 learning process

Introduction and Overview

“Everything that is said, is said by someone.” (H. Maturana)

We Exchange Some Preliminary Information

“So (here we are – in the middle way – having spent many years) Trying to learn to use words, and every attempt

Is a wholly new start, and a different kind of failure

Because one has only learnt to get the better of words

For the thing one no longer has to say, or the way in which

One is no longer disposed to say it. And so each venture

Is a new beginning, a raid on the inarticulate

With shabby equipment always deteriorating

In the general mess of imprecision of feeling,

Undisciplined squads of emotion. And what there is to conquer

By strength and submission, has already been discovered

Once or twice, or several times, by those whom one cannot hope

To emulate – but there is no competition –

There is only the fight to recover what has been lost

And found and lost again and again; and now, under conditions

That seem unpropitious. But perhaps neither gain nor loss.

For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business.

Home is where one starts from.” (T.S. Eliot, “Four Quartets”)

“Home”: Broadly speaking (in this case) denotes the “place” (in space/time) to which we have come in the course of living our lives; that is, the “perspective” and “point of view” to which we have come regarding our relation to the world based in and on our own experiences. In our participatory universe, all observers must acknowledge their (our) implication with what can be known.

Needless to add: attentiveness to scope and limitations of these mental (cognitive, affective) and behavioral (postural/expressive/verbal/gestural etc.) particulars of our personal and social (academic/professional) backgrounds and experiences is part of the whole approach to the learning process. Abstract as they may seem to be, “perspectives” and “points of view” both personally held and socially imposed are altogether real in the sense of conditioning and constraining the sensitivity, scope and penetrativeness of our perceptions of the world and its contents, including ourselves and each other.

(Note how intimately and recurrently, perspectives (our ways of approaching situations) condition/constrain our perceptions and conceptions (i.e. notions of what we “see”).

Note also the widespread use among us of “seeing” as a metaphor for knowing. What do you make of the fact that so many of the verbal tokens of meaning that we have for expressing our sense of “knowing” are rooted in concrete and particular references to the visual sense and “seeing.”

Further to the point: the particular attitudes (cognitively and affectively defined thoughts and feelings, mental sets) that each of us brings with us into this room on this first evening of another “new” semester are bound to influence our perceptions (e.g. of what is actually going on here). And, of course, our perceptions of ourselves in this situation condition and constrain our behavior in response to stimulation arising from the situation—and so on and so forth, in recurrent cycles of mutual and reciprocal causality.

In the late 1890’s, in a notable passage in his justly famous “Talks to Teachers” my favorite psychologist, William James, announces the advent of some new and powerful, down-to-earth, methods of student-centered, hands-on, problem posing, concrete object learning/teaching.

“Verbal reactions, useful as they are, are insufficient. The words may be right, but the conceptions corresponding to them are often direfully wrong. In a modern school, therefore, they quite properly form only a small part of what the pupil is required to do. He must keep notebooks, make drawings, plans, and maps, take measurements, enter the laboratory and perform experiments, consult authorities, keep journals and write essays. He must do in his fashion what is often laughed at by outsiders when it appears in prospectuses under the title of ‘original work,’ but what is really the only possible training for the doing of original work thereafter. The most colossal improvement which recent years have seen in secondary education lies in the introduction of manual training; not because it gives us a people more handy and practical for domestic life and better skilled in trades, but also and even more so because it gives us citizens with an entirely different intellectual fibre.

“Laboratory work and shop work engender a habit of observation, a knowledge of the difference between accuracy and vagueness, and an insight into nature’s complexity and into the inadequacy of all abstract verbal accounts of real phenomena, which once wrought into the mind, remain there as lifelong possessions. They confer precision; because, if you are doing a thing, you must do it definitely right or definitely wrong. They give honesty; for, when you express yourself by making things, and not by using words, it becomes impossible to dissimulate your vagueness or ignorance by ambiguity. They beget a habit of self-reliance; they keep the interest and attention always cheerfully engaged, and reduce the teacher’s disciplinary functions to a minimum.”

Conduct and Administration of Subject

Students: Caveat Emptor

The length and detail of this syllabus is unusual, and requires, at this point, something in the way of an explanation/justification. This is not an ordinary undergraduate subject of instruction like most of the lecture-based classes that you have been in here at MIT.

Think of it as something akin to an open-ended and academically serious exercise in scholarly (scientific) inquiry into the subject before us. We aim to keep to a minimum the time spent “lecturing” while at the same time encouraging everyone in the class to pursue honest hands-on, proactive involvement. This syllabus is intended to provide you with a rather detailed narrative account of the subject before us. For all of its shortcomings and prolixities, the syllabus should suffice both to guide the 9.68 learning system through the topics and to serve as a source of information of the kind that lectures might otherwise focus on. So please read it fully, attentively, actively and frequently.

Fair Warning: Ultimately, the quality of your learning experience in this class will be decisively determined by—and play a role in determining—the quality of everyone else’s. Anyone sincerely aspiring to come away from this class with a quality final grade and a credible, trustworthy and useful understanding of nature and scope of the subject before us must first of all be ready, willing and able to put the stipulated modicum of weekly time and effort into the 9.68 learning process for the next 14 weeks.

Final Grades

Will vary and be commensurable with our evaluation of the quality, timeliness, and consistency of your effort and involvement. Everyone enrolled in this class can and will receive a first-quality final grade (i.e. an A) provided only that each and all of you are ready, willing and able to devote a modicum of 12 hours per week of quality time/effort (participation/observation) to the collaborative learning process that lies at the heart of our approach.

Regular and faithful attendance, punctuality, attentiveness, honesty, sincerity, as well as frequent, timely, and concise formative evaluation (preferably constructive and succinct) are also keys to success. Tapping into the relevant information and framing feedback in an effective way, is not a completely straightforward process. The scope and acuity of our perspectives—like the incisiveness and comprehensiveness of our descriptions of our lived experiences—are ultimately limited by the partiality of our own particular personal and social perspectives (and these, in turn reflect the diversity of our lived experiences).

What knowledge and skills are you hoping and expecting to be able to take away from this class?

What amount and quality of time/effort are you ready, willing and able to put into it? What final grade are you hoping and expecting to end up with?

Think in terms of the full range of available final grades and reflect on the quality of your performance accordingly.

Instructional Subsystem

Steve Chorover

Communication

The difficulties of language are many and varied. Our experience teaches us that it is extremely important for us to be as clear and concise and as open as possible in communicating with each other and with you, our students, regarding what we see as key substantive and procedural issues before us. In your communications with us, and each other, we encourage you to do the same.

This means making serious and sustained efforts to provide classmates, groupmates, and the learning process as a whole with pertinent and timely input and feedback. As already noted, this aims to be a credible and serious instance of human inquiry. In order to be trustworthy, and useful, such an enterprise must embody and reflect values such as honesty, respectfulness, attentiveness, constructive criticism, conciseness, coherence and clarity of communication.

In addressing 9.68-related emails to each other, whether within or between study groups, please feel free to cc. group and classmates, and us as appropriate.

You are encouraged to be yourself while becoming also a serious student of the subject before us. Issues will arise about which you will feel strongly; feel free to voice your opinions regarding substantive or procedural issues directly, to each other and to us either publicly (if appropriate), in study group, in class, or privately during office hours—by chance or appointment. Please do not be surprised if we suggest that the issues you are raising really deserve to be considered by the entire class.

Being there: Attendance and Participation

As already noted, collaborative learning is not a spectator sport. Full, timely and complete attendance and conscientious participation by everyone in all regularly scheduled 9.68 activities is expected.

Consider your Attitudes

Beginnings are important. How are you feeling at the point of entry? Here is some good advice to would-be learners, from Alexander Bain and John Stuart Mill:

“Take care to launch yourself with as strong and decided an initiative as possible.”

“Seize the very first possible opportunity to act on every constructive resolution you make, follow every emotional prompting you may experience in the direction of the habits you aspire to gain.”

“Keep the faculty of effort alive in you by a little gratuitous exercise every day.”

“Pedagogical soundness lies in teachers learning to connect matters to be newly learned with the sort of material with which the pupils’ minds are likely to be already spontaneously engaged.”

Please examine–re-evaluate and adjust as need be&ndsah;your customary “default assumptions” about what is going to be happening here.

In order for you to be able to work together with each other and with us within stipulated time/effort limits [toward the attainment of the hopefully common and explicitly stated subject-related objectives] you need to agree, among yourselves, how you are going to view these guidelines.

Study Groups

In 9.68, we don’t ordinarily focus on details of the group formation process as closely as we do in 9.70. Nevertheless, we view the formation of the 9.68 collaborative learning system as a prototypical instance of a process that can be found (mutatis mutandis) in the organization and development of myriad other human social systems. (If the meaning of this paragraph is not clear to you, please inquire further. See also Developmental trajectories below).

First Group Meeting

As already noted, beginnings are important. You should take some time at the outset to consider the suitability of the “social architecture” of the environment in which you are intending to meet. Get comfortable in your meeting place and start becoming acquainted with each other.

If, as seems likely, this line of inquiry initially leads you to recite the usual facts in the locally time-honored way: (e.g. with clichés relating to past or present MIT courses of study, MIT living groups, MIT classes, etc.) that’s ok. But please try not to stop there. Once you’ve gotten that altogether commonplace part of your introductions out of the way, what else do you have to say to each other? What is special or unusual about you? Who are you? Where are you coming from? Where are you heading? Why are you taking this class? What do you make of it thus far?

“9.68” is what you all have in common here, and all of you have just completed the benchmark questionnaire and been through the first class session. The instructors claim to be trying to foster a hands-on, problem posing, pedagogical approach (aka “collaborative learning”). What do you think about that?

This would be a good time to talk together with your groupmates and classmates about what you are all getting yourselves in to and how you are hoping and expecting to deal with the demand characteristics of the situation. What are your expectations and default assumptions now—has anything changed in regard to your hopes and fears (if any)—concerning the likely developmental trajectory of the 9.68 collaborative learning system and your own involvement in it?

Of course, no two human systems (no two people, families, groups, 9.68 classes, etc. etc.) are exactly the same, but in most cases they seem to become organized and develop in essentially the same way. Hence, we know and can say a few things with some confidence about the process.

Distribute:

- Study Group Roster Forms

- Timesheets

- “Working Groups”

Some Issues To Consider At Your First Study Group Meeting:

- Did everyone make it on time and without incident?

- Has everyone completed the first assignment?

- Evaluate the suitability of your surroundings. Is the “social architecture” of the situation appropriate? Is the place and time conducive to conducting a “study group” meeting? If not, is there a better alternative available?

- Try to get comfortable; say “hello!” politely and “how are you?” This (by the luck of the draw) is your study group and will remain so for the rest of the term. Prepare to listen to each other. Be open to possibly having to revise/update assumptions in accordance with new information;

- How do you want – hope and expect – the class/study group to develop?

- How educationally valuable to you will it be?

- As you introduce yourselves, think about the terms in which you and your peers “normally” define/identify yourselves in MIT undergraduate academic contexts such as this one?

- Try to identify some of the explicit (members of the same organization, roommates, etc.) and implicit loyalties (both “visible” and “invisible”) in the study group and the class as a whole

- Compare/contrast your “first impressions” of this class.

- We are all constantly, invariably, and inescapably engaged in endeavoring to manage the impressions that we make on other people. How are these commonplace efforts at “impression management” influencing your interactions with each other.

- What is your view of the other study groups?

- Why is the class being defined as “collaborative” and being thus organized into “study groups”?

- Are these arrangements intended to be cooperative or competitive?

- Are there any “serious” students in this group? In the class? What do we mean by “serious” in this context?

Developmental Trajectories

Generally speaking, the organization and development of all human social systems is comprehensible as following a timecourse with a characteristic trajectory from beginning to end and moving through a number of more or less separate and distinct phases or stages. We are participating in and observing the organization and development of a system life cycle. This is a process with a characteristic trajectory. Based on prior experience, we can safely expect the 9.68 learning process to traverse—in its own way—an ordered sequence of more or less fixed and invariant stages or phases that may be analogized to conception, gestation, birth, infancy, childhood, adolescence, maturity, old age, senescence and death.

By a hypothesis that you are invited to critically evaluate, there are discernible parallels in the developmental stages or phases of individual and group systems. Of course, each instance is different, but there remain commonalities and parallels (e.g. in the cognitive, affective and expressive demand characteristics of each and all). Moreover, the process is characteristically marked by the tendency of specific, context-appropriate “crises” to arise. (e.g. Approach/Avoidance Conflict, Basic Trust/Basic Mistrust, Power and Control, Autonomy/Interdependence; competition/collaboration; Generativity or Stagnation).

Formative Evaluation

How are you doing in this class? (No, it is not too early to be asking this question.) Reflect on your attitude; on the quality and amount of your participation; do so frequently and recurrently throughout the term. The concept of formative evaluation is applicable to any goal-oriented activity (e.g. a design process). What is going well? What is not so good and needs improvement?

We expect you to participate fully in all stages and aspects of the observation/evaluation process. The Timesheet (see below) is intended to provide a first step in the process of monitoring the amount of time and the quality of the effort per week that you put into making the collaborative learning system work effectively.

Workload

Based on your knowledge of the “MIT system” and applicable nomenclature, please:

- “unpack” the foregoing subject description

- reflect, insofar as you can at this point, on your own inwardly experienced thoughts and feelings about the present situation. For example: with which particular constellation of attitudes have you come? How might your present attitudes be related to your present and future behavior in this class? Might your attitudes be expected to influence (for example) the “seriousness” with which you are ready, willing and able to approach the subject before us?

- share with others your understanding of the stipulated “workload”. Try to make explicit your expectations (hopes, fears) regarding the average amount of time per week to be spent working on it and say something about the general quality of individual and collective effort that you expect yourself and others to be putting into it during the next few months.

Over the years 9.68 has evolved into a 12 unit elective subject requiring of participants a nominal average of 8 hours of solo weekly time and effort completing stated reading, viewing, and writing assignments (e.g. “reaction papers” and other exercises). With a few exceptions we all will meet at this time and place weekly as a class, and everyone meets separately with a study group whose membership has been randomly determined for two hours weekly at a time and place tba and whose main task it is to serve its members and the class as a whole by making appropriate, and constructive contributions to the overall organization and development of 9.68_13. Our central aim is to help in shaping the class into a collaborative learning system of the highest possible educational quality and of the greatest possible personal and social value to those who comprise it.

In such a class, the learning experience is no mere spectator sport. Active participation by all in shaping the organization and development of the collaborative learning system is a basic focus of both the formation and evaluation of the collaborative learning process that serves as the core element of our modus operandi.

Because of the vagaries of the MIT Academic Calendar, the actual schedule of our weekly class meetings is a bit irregular. The workload has been adjusted accordingly but is still not meant to be light weight. The catalog description sets out the terms of the contract implicit in the fact of our participation here. In order for the class to succeed in its objectives everyone involved needs to put in a good faith modicum of time and effort. To be more precise, the class as a whole will succeed if everyone puts into it, on the average, 12 hours per week of high quality time and effort. Let us reiterate the point for emphasis: experience teaches us that success in creating a workable collaborative learning system depends on the readiness, willingness and ability of everyone involved to make—and to expect everyone else to make—a genuine good-faith effort to devote the stipulated modicum of time and effort to the process.

The MFA Field Trip

According to the official MIT calendar there will be no class meeting for the third class. Instead, this will consist of a Field Trip–In Search of Quality—to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (MFA). Once again this year, the Field Trip to the MFA will be conducted as a whole-class outing.

Assignments

The completion of weekly assignments in a systematic, timely and conscientious fashion means doing some things before others. Assignments are meant to be done in the order indicated in the syllabus. Your study group should discuss and agree on a schedule that enables timely completion of required tasks before group discussions.

Required Text

We will begin as 9.68 classes have been doing for more than two decades: with several weeks of reading (perhaps many of us re-reading) and discussing Robert M. Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (William Morrow and Co., 1974). Notably, ZAAMM is a book whose subtitle identifies it as “An Inquiry into Values”. How do “values” relate to “affect”?

You should acquire your own personal copy of this text to have and to hold (and to mark up as need be). There is a cheaper, more compact Bantam or Pocket Book edition, but you are advised to get the larger format paperback edition that the Tech Coop appears to have in sufficient numbers.

Additional Readings

Other readings will be available on the course web site.

Please print out copies to read, to mark-up as appropriate, to keep and to bring with you to study group and class discussions.

Viewing Films

Some of the videos that you are required to watch (and will subsequently discuss in study groups and class) will be accessible from the course website. Others are available online as indicated below.

Feel free to watch videos alone or with classmates/groupmates (in the latter case, the time spent together should not be understood as going toward fulfilling the study group meeting requirement).

Journal-keeping

Would-be serious students are expected to begin at once keeping their own personal 9.68 13 Journal. It is up to you to determine what to put into it, but it is also incumbent upon you to make clear to each other and to us the form that your Journal will take and the manner in which you propose to keep track of and evaluate the quality of your 9.68 experience, including (but not necessarily limiting yourself to) the account of the quality and amount of the time and effort that you will actually be putting into 9.68.

Arguably, we don’t really know what we think and feel until we hear (or read) what we have to say (or write). If you are to do some learning in this class, and want to be in a position to formatively and summatively evaluate it, you’d better start keeping track of the experience. You are advised to get yourself a hard-bound “composition book” in which to make regular entries. If some would prefer to use a portable computer and electronic workfile we will need to have some further discussion before accepting that as a substitute for a hardcopy notebook. If you decide to keep part of your journal electronically, it makes a difference whether or not you also maintain a hard copy version. Searching the web for “keeping a journal” is a good way to find links that discuss the benefits of diligent journal keeping.

At the very least, a journal devoted mainly to this class will assist you in keeping track of your own progress through the 9.68 learning experience. It will also enable you to formulate pertinent comments and/or relevant questions for study group and/or classroom discussions. In this way, the quality of your interventions in the proceedings will be enhanced and likewise will the quality of class and group discussions. Use your Journal as a place to jot down “random” ideas and questions that may come to mind while you are reading (and at other times). Journal entries will also be useful in planning and writing assigned reaction papers. Use your journal as a place to keep track of your thoughts and feelings about the class, the instructors, your classmates and groupmates, the form and content of the subject matter, and the relevance of the collaborative learning process to you.

It is important for all of us to take this personal aspect of the workload seriously. We will not normally require you to submit your journals to us for examination. However, it is incumbent upon “serious” students to keep it handy, to use it consistently, and to have it in hand at all 9.68 activities (class and study group meetings, fieldtrips, etc.) Get used to using it on a regular basis. Our aim is to encourage you to feel safe enough to take some real-world personal risks without fearing unwanted self exposure.

The only foreseeable circumstances under which we would be inclined to ask to see the contents of your journals would be in the unlikely event that you end up feeling or believing that our evaluation of the quality of your performance (as reflected in the final letter grade assigned to you by us) significantly underrates the quality of your actual performance and this becomes a seriously contested issue between us.

In evaluating your 9.68 performance, we will generally rely on a five-point scale as specified in the MIT course catalog (excellent, very good, good, fair, poor or failing). It’s the amount and quality of your own personal participation that matters!

Keeping a Timesheet

Many people find this a difficult discipline to adopt, but our experience tells us that it is very important to keep track of your own performance. To help you monitor day-to-day, week-to-week, quantitative/qualitative overall time and effort of your 9.68 performance in real time, a printed form is appended. You should make entries no less frequently than three times per week, even if you need to consciously force yourself to do so. Learn to use it conscientiously: make timely and truthful entries and bring it with you to class and be prepared to make it available for occasional inspection.

Writing Reaction Papers

“Everything that is said is said by someone.” Papers will normally be 1–2 pages in length on topics to be assigned. You are responsible for printing your own papers. Insofar as possible, all assignments and reaction papers for 9.68 should be written in the voice of the first person singular and be the product of your own mind and hand (mens et manus). Please do not misunderstand, we are not trying to discourage you from consulting or discussing or quoting from or otherwise relying on the work of others. On the contrary, conscientious reliance on the work of others is both a necessary and a desirable hallmark of all serious scholarship. Insofar as the views of others are relevant in this connection, you should feel free to use their ideas and words as frequently and freely as necessary; just make it a point to acknowledge your sources in each and every case.

A Caveat: The advent of the internet and the ease of access to information of dubious credibility via the world wide web presents us with the problem (to put it crudely) of “distinguishing shit from shinola.” Some entries (not to mention whole web pages) are here today and gone tomorrow. And some are extremely misleading. It is advisable to be duly cautious in evaluating such information. You will surely get into trouble in this regard if you don’t carefully check and cross-check both the credibility of the source and the validity of the information.

Plagiarism

Intellectual property law defines it as a form of grand theft, and in the context of academic life, borrowing words and phrases – whole paragraphs, even – without properly acknowledging your source is the kind of larceny that poses a perpetual threat to the integrity of serious scholarship. Do you understand this? You are probably not the first or only one who has come to hold more or less strong opinions of the kind you are endeavoring to articulate. Sometimes it seems like something you read has an unmistakable ring of truth for you or someone else seems to have already put into words something very like what you believe to be your own present conclusions. That’s ok. Use your own words and voice, insofar as possible. If you feel your thesis would be strengthened by weaving into it the eloquent testimonies of others, including recognized authorities, that’s perfectly OK too. Feel free to copy or quote whole sentences (paragraphs, even) from the written or spoken work of others as need be. But, whenever you do so, make sure that you use “quotation marks” and fully cite the sources that you’re borrowing from.

Paper Chase Format

Assigned reaction papers and other submitted texts are to be conventionally footnoted (if necessary), carefully composed, typed, and proofread. The instructors may sometimes ask your permission to redistribute submissions so that each of your papers may be read/reviewed and commented on by one or more of your classmates/study-group mates. Please, submit no handwritten papers unless absolutely necessary and unavoidable (and approved by us).

Unless otherwise arranged in advance, all students will personally submit each and all of their own assignments to the instructors per their request, by hand, and in hardcopy form, at our weekly class meetings. Please, no proxies. The use of group-mates as surrogates to hand in your hardcopy in you’re absence is not permitted, except by prior arrangement.

Ideally, your scheduling of tasks will permit you to develop a routine in which reaction papers are drafted in a timely way and can be shared among study group members, we also want to afford opportunities for you to give/receive constructive feedback to/from groupmates and classmates before submitting your own final versions to the instructors.

Except for the final term paper (see below) no letter or number grades will be assigned to the written work that you turn in. However, it is our intention to carefully and completely read all timely submissions and to provide prompt and constructively critical feedback, in writing, on the quality of content and form at or before the relevant class session. Tardy submissions will be received and recorded as such and may be returned unread.

What is Collaborative Learning?

We define the groups that we have randomly formed (and their individual members) as 9.68 subsystems. This leads into a discussion of the “systems approach” to be taken. At the outset, a distinction needs to be drawn between cooperative and collaborative learning. See, e.g. Tough Questions: “What’s the difference between collaborative and cooperative learning?”

We aim to create a classroom environment conducive to meaningful collaborative learning. We hope and expect that each and every one of you will find it both fun and informative—a quality learning experience.

Quality collaborative reaction papers (and term papers/proposals explained below) are welcome; however, don’t be tempted to engage in collaborations with expectations conducive to mere dilution. Quite the reverse should be the case: these should be meaningful concentrations of effort all-around. Several heads are only better than one if there is no freeloading and if all members are “operating on all cylinders”. To be worthwhile, the process of producing collaborative projects or papers should involve more than merely stitching together a series of separate sentences written by different people. Meaningful collaboration means working together to achieve a high degree of effectiveness through constructive interdependence. Accordingly, expect it to require significant cooperation between and among authors for papers to exhibit a high level of internal consistency, coherence, conciseness and continuity.

Planning/Producing End-of-Term Project or Paper

This can be on almost any topic and can take almost any tangible form (which must include documentation), provided that its form and content be clearly and coherently relevant to the subject matter dealt with in 9.68. Generally speaking, the choice of topic should be based on your own personal/social (e.g. academic/professional) experience and interests. It is up to you to show in your proposal how what you want to do relates to an aspect or aspects of the material dealt with in this class during the term.

Term project/paper proposals will be submitted for prior approval. Proposals (not to exceed 2 pages in length) are to be turned in via the instructor before class session 10 (no class on that day). Proposals will be reviewed and returned to you with comments within 5 days. Unless other arrangements are made beforehand, term papers are not to exceed 15 double-spaced pages in length, including notes and references. The deadline for submission and verbal presentation of fully completed term projects/papers is the beginning of the final regularly-scheduled class (i.e. Class session 14). Extensions will be granted only by prior arrangement and only under extreme circumstances.

Interim and Final Grades

Final grades will be based on the instructors’ evaluation of the quality of individual term- long performance in all aspects of the subject including our assessment of the timeliness, conscientiousness, and skill with which assignments have been undertaken and completed, and our perception of the overall quality of your (1) written work, (2) study group involvement, (3) classroom participation (in general) and (4) final term paper/project (in particular).

A Final Note About the 9.68 Learning Process

Each element of the curriculum is intended to be approached in a particular way—with everyone encountering each activity in the same sequential order.