Portable low-cost defibrillator rechargeable through the ambulance’s power.

Team: Divya Srinivasan, Michael Melgar, Krithika Shanmugasundaram, and Swetha Kambhampati

This content is presented courtesy of the students and used with permission.

- Hello to our favorite superheroes!

- Trains of thought

- Conversation with Mario Luque Aguilar (83685544)

- People

- Conversation with Dr. Sergio Shkurovich, PhD

- “Day” flashes

- Making progress is wonderful! :)

- First attempt at the differential amplifier and noise filters done

- Explanation of the two filters

- Ideas for signal visualization

- Shock delivery details

- Meeting With Prof. Roger Mark

- Paul helped debug the differential amplifier

- To Do List

- The Longest Yard

- USAID Presentations

Hello to our Favorite Superheroes!

by Krithika Shanmugasundaram

Just wanted to give a quick shout out to all of D-Lab Health Spring 2010 and announce the presence of the Ambulance Team’s blog. I encourage you all to post your unfiltered thoughts and suggestions on this. We would appreciate any input from people that are as committed to saving the world as you all are.

One request: please post your favorite super-power at the end of every comment.

A quick piece of background and foreground on our project:

The motivation for our project was the simple (yet shocking, for me anyways) reality that hospitals in Nicaragua strip the ambulances of equipment because they claim they have a greater need for it. However, this makes it difficult to give care to patients wile transporting them, which is often necessary, as in the case of severe bleeding, cardiac arrest, and mothers in labor.

Our challenge is to incentivize the retention or, at least the return, of ambulance equipment. Ideas have included making modular instruments/equipment that would increase the ease of returning equipment to the ambulance and also make it look like it belongs more so in the ambulance than the hospital. This also combats the hazard of loose wires that are hanging from the inside of the ambulance since the equipment is literally ripped from walls it is attached to.

Photo by Anonymous MIT student. Hospitals had stripped the ambulance clean of its medical supplies.

Trains of Thought

by Krithika Shanmugasundaram

These were our potential projects:

1) Integrated vital signs monitor- being able to monitor pulse, O2 saturation, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and temperature are necessary when transporting an unstable patient to the hospital. If all of the instruments needed to do this were connected to and wired into one box, it would be cumbersome and wasteful for the hospital to take the box and keep it, because they may only need to use one or two of the functions at a time for particular patients. It might also seem out of place in a hospital where large, specialized, fancy machines reign and bring pride to the physicians and nurses that provide care there.

Problems: We figured out that the ambulance usually took a doctor or nurse with them on calls, and these medical professionals had the ability and brought the equipment to monitor BP, pulse, and temperature. This makes 3/5 functions of the “vital signs box” unnecessary. It would not be effective to just have two vital signs monitored in this device because it would not provide enough incentive to keep it in the truck.

2) Low-cost AED/Defibrillator – we were inspired by the untouched EKG at the hospital in Ocotal. Although functional, people were frightened by its complexity and potential dangers with unintentional misuse and we also found that no one knew how to use it. If used properly, a defibrillator could save the lives of cardiac arrest patients, who often cannot afford to wait the 15-25 minutes it takes to drive to the hospital to get care. This is an area where en route care is a priority and can be the life-saving step.

Problems: There are dangers with working with a high-voltage circuit. The circuitry is difficult in itself, and would be more than a 4-week project.

3) Making the Defibrillator specific to the ambulance – the idea was to design a system that would be able to convert the 12 V from the cigarette lighter in the car to the 200 joules needed to deliver the adequate number of shocks (4-5) to a cardiac arrest patient. The cigarette lighter would be the only way to charge it, so it would have to make its way back to the ambulance eventually, but patient care would not be compromised, since the charged defib could be transported with the patient if needed.

-Note: other ways to provide incentive to keep the defib in the ambulance are 1) to create a flashing light or annoying beeping sound that goes off when the device is kept away from the ambulance for too long a time 2) or to actually disable the defib when it spends too long away from the ambulance.

Problems: The hospital may still just keep the defib, since it won’t run out of battery all that quickly, since it will not get used that often. The issue of making a vehicle-specific charger has also been done before (airplane flash lights charged in holder bound to the plane), so this aspect of the project would not be that interesting.

4) O2 purification system – one of the simplest items of an ambulance that can do a great amount of good in a variety of situations is the O2 tank. The shortage of O2 tanks could be compensated with an O2 generator/extractor. The idea was proposed as an “O2 catcher” that would sit on top of the ambulance and as air sped by it would only bind the O2 and keep it in a container. Our challenge is to use electrolysis to produce the pure O2, collect it efficiently, and pressurize it so that a large volume can be held (15 L/min is standard flow rate, and with an estimate of 15 min transport time, it comes out to 225 L, at least per transport)

Problems: We are in the process of hammering this one out and doing the calculations (to come soon!) to figure out how much water will be needed to produce this O2.

Those are I think projects we thought about, mostly in the order we discussed them.

{Spidey- sense}

Conversation with Mario Luque Aguilar (83685544)

by Michael Melgar

Sivakami and I spoke on the phone with the ambulance driver we met in Sabana Grande. We spoke about the situation with cardiac care patients he deals with and about the need for oxygen on the ambulance. Interestingly, he said that he does run into shortage because there is an 8 day turnaround time for an empty tank to be shipped, filled, and returned. He usually has no oxygen available, and he estimated it is needed 2 or 3 times per week. Because of this, having a system that automatically and sustainably generates oxygen on the ambulance would be helpful. Perhaps something built-in that uses the car battery to power a device that forces the gas into a pressurized container.

I actually still prefer working on the defibrillator, though, and there are also excellent reasons to do so. Mario said that he transports about 5 cardiac arrest patients per month. These patients have no access to a defib until they reach the hospital in Ocotal or in Somoto, which takes 30-40 minutes (to the health post at Sabana Grande) plus 20 minutes (to Somoto). The nurse on board treats these patients with ‘chest massages,’ which I took to mean CPR (is this correct?). As an anecdote, he transported the same patient 3 times since our visit to Nicaragua. This man apparently suffers heart attacks almost once a week. The first two times, he was transported to the hospital, but the third time stabilization at the health post was enough. This makes me wonder if we’re talking about the same thing when we say ‘heart attack’. He also said that patients always make it to the hospital in time to be defibrillated and saved. Can 40 minutes of CPR save a heart attack patient? The symptoms he described seemed to be those of a heart attack, though: shortness of breath, loss of consciousness, convulsions, and even coughing up blood.

Some infrastructure related information we collected: Each municipality has two ambulances. Totogalpa uses one for patient transfers between health posts and hospitals and the other for emergency cases. If Mario had his way, he would simply weld a defib into the ambulance, making it impossible to remove. Lastly, we got the contact information of three other people: Ismael, the ambulance driver in San Juan de Rio Coco (88536960); Dr. Blanco, the director of the Totogalpa health post (84005324); and Dra. Janet Veillez, another doctor who periodically makes visits to the health post and has a contact in the U.S. (86282017). The next step will be to follow up with one of these people. He/she may be able to clarify what is meant by ‘heart attack’ and provide feedback on our ideas.

{I can spell ANYTHING.}

People

by Divya Srinivasan

We haven’t been having much luck lately in contacting people. On Thursday and Friday members of our group contacted various professionals linked to AED technology. Below are the people contacted and what sort of expertise is associated with them.

People Contacted Prior to April 25, 2010:

- Varsha Keelara: A medical student at HMS, Varsha has a lot of experience dealing with AEDs. She also has a lot of contacts who she could refer us to, but unfortunately we haven’t heard back from her yet.

- Dr. Robert Malkin at Duke University: Dr. Malkin is a professional at Duke who has made a circuit that can test the voltage of the defibrillator. Our assumption is that because he has dealt with defibrillators before and high voltage circuit components, he will be able to tell us how one works or how to program the different components.

- Ed Boyden: He is a professor at MIT’s Media Lab and has expertise in various areas of biomedical engineering. He is an electrical engineer which will allow us to gain a better understanding of how to make circuits.

- Professors of 6.022: All 3 of them. We contacted them because we talked to Aubrey, a student of the class and an EMT. She talked about how she had experience with EKGs from 6.022. We’re hoping that they can help us figure out how to detect and analyze fibrillation.

- Jon Wu: A medical student at Tufts University, he has a fair amount of knowledge about EKGs and defibs.

- Aubrey Samost: An EMT and a student in 6.022 (refer to above), Aubrey gave us some helpful regarding how EKGs detect fibrillation and how it calculates the different conditions of a patient. She is a good bouncing board for ideas and could direct us to professors she has had in the past.

Here are the Questions we Asked them in our Emails:

- What does an AED look for?

- How does the AED detect the signal?

- How do the leads interact with each other to detect the signal?

- How do you analyze the signal? What does fibrillation look like versus a normally beating heart? Healthy v. shocked v. you’re a goner.

- Do you have any ideas for keeping a defib in an ambulance?

- Do you know anybody else who would be able to answer our questions?

We haven’t received responses from any of these people and are hoping to either get email responses back from them or call them directly if we can find their phone numbers. If you have any ideas of contacts we should get in touch with or any questions we should ask these professionals - that would be great! Until tomorrow, this is the “happiness-G” signing off!

Conversation with Dr. Sergio Shkurovich, PhD

by Krithika Shanmugasundaram

We called Dr. Sergio Skurovich, the director of International Regulatory Affairs at St. Jude Medical. He works in the cardiac rhythm management division and he had some good advice for us in our pursuit of the AED.

In our e-mail correspondence, he clarified that a defibrillator senses electrical signals measured from the skin. These vectors are similar to those in an ECG, but different to the standard derivations used to collect a surface ECG:

“During a normal rhythm (called sinus rhythm), there is a clear sequence of events marked by atrial activation (P wave on the ECG) followed by ventricular activation (QRS complex on the ECG) and finally ventricular reset (T wave on the ECG). When the ventricles fibrillate, the normal electrical pattern P-QRS-T disappears and is replaced by a less organized, higher frequency and lower amplitude signal.

Sinus Rhythm: http://www.ecglibrary.com/norm.html

Ventricular Fibrillation: http://www.ecglibrary.com/vf.html”

On the phone we discussed what materials we would need to build the sensors on the defib pads and he indicated that the electrodes detect polarization and repolarization, and are usually made of silver and silver chloride. He further instructed us to take guidance a chapter from the book Medical Instrumentation: Application and Design by John Webster called “Biodetection Electrodes.” Conveniently available on Amazon. Inconveniently over our $100 budget…

Some issues he brought to our attention were that noise could be picked up from electrodes and cause false positive signaling, and that low-cost AEDs were available (from Metronic, WA and Philips for <$1000). However, $1000 is still fairly expensive for each ambulance. The components that contribute most to the cost are: a reliable, rechargeable battery, good capacitor, speedy charge delivery, and an interface for the user (i.e. voice box). These will most likely be the aspects we will focus on.

We then asked if he could direct us on how to perform signal processing and if there was a quantifiable method of detecting V-fib. He suggested we could try using frequency along with amplitude and the QRS-complex characteristics to determine an algorithm for indicating a necessary shock. He also mentioned that there is lots of literature available on this topic and we should go through that for more specific details and instructions. Programs we could use to automate the signal processing include MATLAB®.

The question of whether to make an AED vs. ED was then brought up. Sergio proposed perhaps having a laminated “instruction sheet” on the machine that clearly shows the graph of a V-fib reading and normal heart reading and instructs them to only shock when it is clearly in V-fib.

After discussing with Jose, we decided to work on an ED, perhaps using a flash from a disposable camera as our “defibrillator.”

{spidey-sense}

"Day" Flashes

by Divya Srinivasan

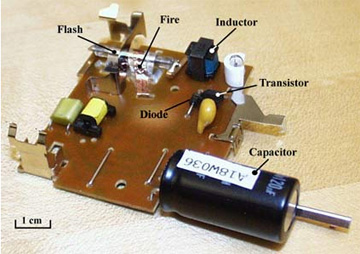

Photo courtesy of David Gossard, from the MIT OpenCourseWare site 2.003 Modeling Dynamics and Control I, Spring 2002. The electric circuit from a disposable camera.

In D-Lab yesterday, we channeled our inner 3-year olds and demolished (gently) a disposable camera. What we found was a beautifully exquisite piece of circuitry with a pretty big capacitor to charge and discharge the voltage from a double-A battery. Though Michael got shocked a couple of times in the process, we found out that once the battery was in place, the capacitor was charging continually. When we connected a wire from the capacitor to a metal piece on the circuitry, the capacitor discharged and there was a resulting flash from the light attached to the circuit board.

Our goal for tonight is to attach a resistor to the capacitor so that it will cause the capacitor to charge slowly and reduce the hazard of shocking anybody. Michael and Krithika were able to meet with one of the 6.022 professors today afternoon (more to be posted later!), so we’re going to see if we can start working on the coding/sensory aspect of our defib.

What we’ve completed so far:

- Picking apart a disposable camera, isolating the circuit, and making the capacitor discharge to create a flash!

- Consulting professors on how exactly we’re going to gather data from a person and how to analyze that data to create graphs of a patient’s signals.

{Happiness-G}

Making Progress is Wonderful! :)

We’ve made significant progress in the past couple of days– it’s pretty exciting! Yesterday, we started to make our own differential amplifier in a course 6 lab in building 38. Using the circuit diagram that we obtained from Maysun (see below), we started to piece the diff-amp together. We will be using this differential amplifier to take the voltage difference between the two leads and amplify it 100 fold. This will serve to increase the signal taken from the leads so that the computer can then analyze and produce the graphs on the PeggyBoard (as the output). Our goal for today is to finish wiring the diff-amp, acquire the leads for the defib, and the PeggyBoard, and start coding the program that will analyze the signal to produce the output graphs.

In a couple more blogposts to follow, we will detail our conversation with 6.022 instructor, Professor Mark, and other email communications we have had in the past couple of days.

First Attempt at the Differential Amplifier and Noise Filters Done

by Michael Melgar

After long, arduous hours at D-Lab, Divya and I have built three of the circuits needed for a functional ECG. Whether or not they have been assembled correctly remains to be seen with use of an oscilloscope with Paul’s help. The differential amplifier is designed (by choice of the resistances used) so that it takes in a signal from two points and subtracts their voltages before multiplying by 100. The inputs will be connected to the electrodes attached to the patient, so our signal of ~1 mV should be amplified to ~100 mV. At times the circuit was subtracting input voltages, but failing to multiply by 100. Testing with only a multimeter, I was unable to troubleshoot the problem, but using an oscilloscope should make it much easier. (Paul’s expertise can’t hurt either).