In this section, Dr. Sastry shares the intentions behind the three components of the pre-trip assignments that the student teams deliver to their respective host organizations.

| RESOURCES FOR Mentor Meetings |

|---|

|

In preparing for the trip, as well as in reflecting upon the on-site work, students benefit from the meetings that they have with their faculty mentor. For mentors: For students: |

Work Plan

When students select the projects, they have a description of the problem or opportunity that the organization is facing and also the host’s ideas about how to address that problem. One of the challenges is that sometimes what the client or partner wants is not what would be most useful to them. This is a well-known phenomenon. We want to recognize that and not treat it as a problem, but as part of the work. This is part of being a professional: hearing what you are being asked to do, understanding that, and probing that thinking. Students have to build a sophisticated dialogue to develop and advocate the optimal approach. Once assigned a project, students are required to understand the setting, the organization, its history, and basics about the country. What follows is a real discussion about the challenge or opportunity, and how to connect the host’s goals with the problem. We build causal maps that help link those things, and this helps create a definition of scope and a work plan. The students are asked to address the open questions, prepare for areas of uncertainty, and anticipate ways to discover new things. That becomes the guiding document, the work plan, which students discuss with their mentors and their hosts.

Annotated Bibliography

The people we work with are trained doctors and nurses who are now doing double-duty as managers and leaders, and their time is precious. It is not easy for them to read lots of literature to glean new ideas. One way we help in this area is by arriving at every site with a small collection of curated resources. This could be five journal articles about how to apply thinking about service delivery in the consumer sector for health care, or research on new methods of using mobile health tools for maternal health issues. Whatever that collection is, even if they are not all spot-on, partners tend to say that it is helpful to have that small curated set of papers along with the students’ annotations. The literature review gives a consistent framework and some research-based ideas that we can further explore. Students can appreciate the work, the challenge, and the opportunity of going from research to an idea, to a paper, to practice. The whole arc of the course is actually right there in those elements.

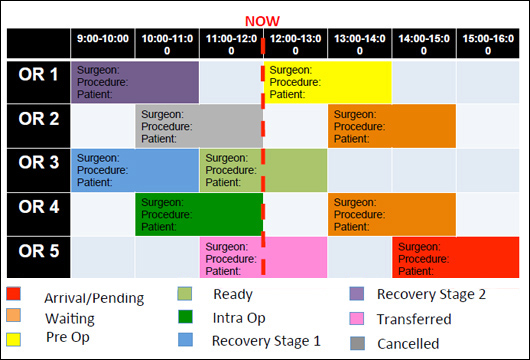

Students from one team analyzed patient flow and operations at a local hospital in Boston as part of their interim study. Figure courtesy of Ali S. Kamil, Dmitriy E. Lyan, Nicole Yap, and MIT Student. Used with permission.

Interim Study

Students are required to complete an interim research study. For a project-based course that involves travel, all the attention zooms in on the travel, and it is easy to see why. But in reality, the trip is worth very little if it is not bookended with preparation and reflection. I am really committed to using the period before students go as a time for thinking and research. It is not just planning, but a significant piece of work that will equip them to be well-prepared when they arrive. Hosts often say, “Don’t come to my clinic, or hospital, or company, and just parrot back to me what you’ve learned from me by reading my website. Come here with something I never knew.” If students can arrive on day one with something of value that starts a new way of thinking, it is a real gift. We cannot always get it right because by definition the students have not been there yet, but if they make a good effort guided by interactions with the host, the teaching team, and the mentors, they can arrive with really intriguing ideas that can push everybody’s thinking in new directions.

For instance, a team might arrive with mini case studies on other organizations in wildly different industries. For a non-profit that is trying to distribute health commodities in rural settings in sub-Saharan Africa, students might arrive with a case study of 7-Eleven and its social marketing strategies. And the host can really get excited about that. “Oh! 7-Eleven has daily dashboarding. They have a really sophisticated information system. Can we borrow those ideas and use them in our organization here in Tanzania?” We can say that we are trying to learn as much as we can about the host organization, the country, and the setting, but we have also paired that with an outsider’s perspective.

For some teams, it makes more sense to arrive with a methodology or a toolkit, or a set of interview protocols and plans that they have field-tested here. If they are going to a specialty hospital, maybe they will visit a number of similar hospitals here and arrive with observations and ideas about practices that might be transferrable. As you can imagine, because we only have about five and a half weeks from the first day of class to when they leave, fitting all of that in alongside getting visas and booking flights is a challenge.