In this section, Prof. Beinart explains his perspective on approaching the course content as well as how that has influenced the material presented in the course.

Using Examples to Explore Theory

From Kevin Lynch’s early work, you can already see that he was attracted to the style of thinking from the Chicago School, which is very American in that it connects theory and practice. If I were teaching this course in France, I would never have to show an example. I would simply build theory upon theory, which would be very difficult because I am not a philosopher.

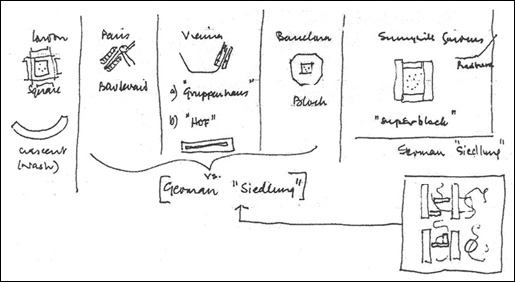

A diagram from Prof. Beinart’s lecture notes comparing the London Square, Paris Boulevard, Vienna Gruppenhaus / HOF, Barcelona Block, Sunnyside Gardens “superblock,” and German “siedlung.”

Instead, my course is built upon:

- important ideas, even if they’re just appearing, and

- relevant examples, which follow any theory or proposition that I propound.

In that sense, there is a binary quality to nearly every idea discussed in the course. For instance, take the invention of the mortgage system. I argue that London is one-third of the density of Paris, and this phenomenon is partly because of the mortgage system. But that in itself does not explain American behavior because the absence of the mortgage system is one of the causes of the Great Depression in the 1930’s here in this country. Though suburban American and low-density London are not easy associations of the mortgage system, I try hard to make the connection.

All theory is messy. There are always pieces that you cannot quite get to fit, but more people are trying to find ways of understanding messy theory. And so, the subject will continue to change.

Teaching Theory through a Personal Lens

When teaching, it is important to take the ideas and theories, recast them, and reshape them into a personal profile of the subject. While it can be totally personal, it still has to address the universal ideas. It is an intersection of sorts that represents a particular piece of the larger picture.

I would try to encourage the people who teach urbanism to know the field and feel secure enough in it to treat their own knowledge and experiences as important. Teaching anything involves your knowledge of the study and your subjective knowledge of yourself. You have to be really frank about yourself, and the things I do not know how to do are the things I avoid. I cannot teach what I do not know, and it takes a lot of courage to admit that; at least for me, it took a lot of courage. Only as I grew in the subject and received feedback did I become more and more successful.

MIT has this air, which I think I have felt somewhat comfortable about, and it pushes the individual to know the field that one studies or is teaching, but with a personal slant. This translates to the design field as well, which inherently is a field that deals with the proper teaching of objective knowledge through the lens of the subjective system. “I am here to teach you what I know about designing,” and “I am here to teach you what the world has gained as knowledge about designing,” are two very different things.

History and Memory

All I try to do in the course is to convey some of the basic issues in urban design and the form of cities. Understanding much of this material comes from an examination of history. Science teaches its body of work without history. Of course, you need to know who Einstein was, or Faraday, or Kepler, but you do not take classes in history. On the other hand, there is no teaching of the fine arts without history. You cannot learn to play music without knowing who Mozart was. You cannot learn to paint without knowing who Francesca was. You cannot learn architecture without knowing who Palladio was. You cannot become an architect without, in some way or another, having read Banister Fletcher’s book. But somehow you can learn urbanism without knowing one city’s history.

Urbanism is now starting to develop both as an art and as a science. The new field of quantitative urbanism will not displace history. Even in science, what is known is always part of the problem of what you discover. According to my friends who teach medicine, if you do a PhD in gallbladder disease, three-fourths of the thesis is devoted to reviewing all precedent literature. There is always the intellectual availability of ideas and practices that have happened before you and before our time. Because of this emphasis and reliance on precedents, I think that Lynch and I both decided to include as much historical material as we could. In my version of the course, I personally decided that the relevance of the Modern Period and the history of the Modern Period are greater than that of history of the ancient, archaic, or classical cities.

To delve deeper, I believe in the difference between history and memory. I have always had a curiosity in writers who are fascinated by memory. Maurice Halbwachs, who wrote the book The Collective Memory, influenced me greatly. I did not think much of memory versus history until during a conference I chaired in Jerusalem. There were historians, practicing architects, and theorists; the discussion of the Holocaust Museum in Washington came up, in which the architect said that he relied much more on memory than on the history of the Holocaust. He showed that in his building, he tried to incorporate memorial elements through the use of bricks and steel.

In the future, I think that our discipline is going to become much more concerned with memory. There is some connection between our daily lives and the presence of memory, which I believe will become an interesting aspect of the theory.