-

Introduction

- Last time: Atomicity via logging. We’re good with atomicity now.

- Today: Isolation.

- The problem: We have multiple transactions—T1, T2, .., TN—all of which must be atomic, and all of which can have multiple steps. We want to schedule the steps of these transactions so that it appears as if they ran sequentially.

- Naive solution: Run transaction sequentially with a single global lock.

- Very poor performance.

- Better solution: Fine-grained locking. But we all agreed that this was error prone back in the OS section. What to do?

-

Serializability

- What does it mean for transactions to “appear” as if they were run in sequence?

- That the final written state is the same?

- That the final written state + intermediate reads are the same?

- Something else?

- It depends! There are different types of “serializability”. The right one depends on what your application is doing.

- Final-state serializability: A schedule is final-state serializable if its final written state is equivalent to that of some serial schedule.

- What does it mean for transactions to “appear” as if they were run in sequence?

-

Conflict Serializability

- Two operations conflict if:

- They both operate on the same object.

- At least one of them is a write.

- Definition should make sense: Concurrent reads are generally fine, but problems arise as soon as writes get involved.

- A schedule is conflict serializable if the order of all of its conflicts is the same as the order of the conflicts in some sequential schedule.

- By “order of conflicts” we mean the ordering of the steps in each individual conflict.

- See Lecture 17 slides (PDF) for examples. A schedule can be final-state serializable but not conflict serializable.

- Two operations conflict if:

-

Conflict Graphs

-

Nodes are transactions.

-

Edges are directed.

-

There is an edge from T_i to T_j iff:

- T_i and T_j have a conflict between them.

- The first step in the conflict occurs in T_i.

-

Example 1:

T1T2write (x, 20)read (x)write (y, 30)read (y)write (y, y+10)There are three conflicts:

T2: write (x, 20); T1: read (x) T2: write (y, 30); T1: read (y) T2: write (y, 30); T1: write (y, y+10)In each transaction, the first step is in T2. Conflict graph is: T2 -> T1.

-

Example 2:

T1T2read (x)write (x, 20)write (y, 30)read (y)write (y, y+10)

Now our three conflicts are:

T1: read (x); T2: write (x, 20) T2: write (y, 30); T1: read (y) T2: write (y, 30); T1: write (y, y+10)Our conflict graph here is T1 <–> T2.

(Note: this schedule was final-state serializable but not conflict serializable.)

-

Example 3:

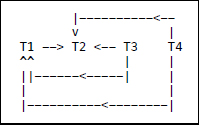

T1:T2:T3:T4:read (x)write (x)read (y)read (y)write (y)write (y)write (z)The conflicts here are:

T1: read (x); T2: write (x) T3: read (y); T1: write (y) T3: read (y); T2: write (y) T4: read (y); T1: write (y) T4: read (y); T2: write (y) T1: write (y); T2: write (y)The conflict graph is:

-

Acyclic conflict graph <=> conflict-serializable.

- Makes sense: conflict graph for any serial schedule is acyclic.

- But we won’t formally prove this.

-

-

Interlude

- We’re going to explore conflict serializability in more depth because it’s useful in practice.

- As of right now, we have no methodical way to create conflict serializable schedules.

- We can check if a schedule is conflict serializable, but if we want a conflict serializable schedule the best we can do right now is keep generating random schedules and testing until we find one with an acyclic conflict graph.

- We’ll get to this, don’t worry.

-

Two-Phase Locking (2PL)

- So how do we generate conflict-serializable schedules?

- Via two-phase locking:

- Each shared variable has a lock (fine-grained locking).

- Before any operation on the variable, the transaction must acquire the corresponding lock.

- After a transaction releases a lock, it may not acquire any other locks.

- (Proof that 2PL => conflict serializability is coming.)

- Note: Fine-grained locking but in a systematic way.

- Why “two-phase”? We see two phases:

- Acquire phase, where transactions acquire locks.

- Release phase, where transactions release locks.

- Immediate problem: 2PL can result in deadlock:

T1T2acquire (x_lock)acquire (y_lock)read (x)read (y)acquire (y_lock)acquire (x_lock)read (y)read (x)release (y_lock)release (x_lock)release (x_lock)release (y_lock)- One solution to deadlock: Global ordering on locks. Not very modular.

- Better solution: Take advantage of atomicity and abort one of the transactions.

- Seems like we’re punting, but is actually very elegant; given atomicity, aborting is a-okay.

- Detecting deadlock is possible:

- Use “wait-dependency” graphs, which capture the locks each transaction has and the ones it wants. Cycle in wait-dependency graph => deadlock.

- Or just abort a transaction after X seconds (X “reasonably” large). Not as elegant, but simpler.

-

Performance Improvement: Reader-Writer Locks

- Reader-writer locks.

- Rules:

- Can acquire a reader lock at the same time as other readers.

- Can acquire a writer lock only if there are no other readers or writers.

- What about fairness? If readers keep acquiring the lock, and a writer is waiting?

- Typically: If writer is waiting, new readers wait too.

- Reader-writer locks improve performance.

- As described, they allow for concurrent reads.

- We can also release read locks prior to commit

- Why? Once a transaction T has acquired all its locks (reached its “lock point”) any conflict transaction will run later.

- If T reaches its lock point and will no longer access X, releasing read locks on X will be fine.

- Hold write locks until commit, though, in case the transaction aborts.

- Can also improve performance by relaxing our requirements for serializability/isolation.

- Read-committed or snapshot isolation (see hands-on).

- See also PNUTS in recitation next week.

- Important: There are a ton of tradeoffs between performance and isolation semantics.

-

Another Possible Performance Improvement: Giving up on Conflict Serializability.

- Sometimes conflict serializability can seem like too strict a requirement.

- Example:

T1T2T3read (x)write (x)write (x)write (x)Conflict graph:

- Not acyclic => not conflict serializable.

- But compare it to running T1, then T2, then T3 (serially).

- Final-state is fine.

- Intermediate reads are fine.

- So what’s wrong? Why shouldn’t we allow this schedule?

- This schedule is view serializable, but not conflict serializable.

- Informally: A schedule is view serializable if the final written state as well as intermediate reads are the same as in some serial schedule.

- Formally, for those interested (this will NOT be on any exam):

- Two schedules S and S’ are view equivalent if:

- If T_i in S reads an initial value for X, so does T_i in S'.

- If T_i in S reads the value written by T_j in S for some X, so does T_i in S'.

- If T_i in S does the final write to X, so does T_i in S'.

- A schedule is view serializable if it is view equivalent to some serial schedule.

- Two schedules S and S’ are view equivalent if:

- Why focus on conflict serializability when it seems too strict? Why not focus on view serializability?

- View serializability is hard to test for (likely NP-hard). Conflict serializability is not, since checking whether a graph is acyclic is fast.

- We have an easy way to generate conflict serializable schedules (coming shortly).

- Conflict serializable schedules are also view serializable, so technically this means we have an easy way to generate view serializable schedules. But we don’t have an easy way to generate view schedules that allows for ones like the example above.

- Schedules that are view serializable but not conflict serializable involve blind writes: Writes that are ultimately not read. These are not common in practice.

- Basically: Conflict serializability has practical benefits.

-

Summary

- Now: Have atomicity and isolation working on a single machine (concurrent transactions, good performance, etc.).

- Next week: Distributed transactions.

Proof that 2PL produces a conflict-serializable schedule:

-

Suppose not. Suppose the conflict graph produced by an execution of 2PL has a cycle, which without loss of generality, is T1 –> T2 –> … –> Tk –> T1.

-

We’ll show that a locking protocol that produces such a schedule must violate 2PL.

-

Let the shared variable—the one that causes the conflict—between T_i and T_{i+1} be represented by x_i.

T1 and T2 conflict on x1

T2 and T3 conflict on x2

…

Tk and T1 conflict on x_k -

This means that:

T1 acquires x1.lock

T2 acquires x1.lock and x2.lock

T3 acquires x2.lock and x3.lock

…

Tk acquires x_k.lock and x_{k-1}.lock

T1 acquires x_k.lock -

Time flows down in the above step. Since the edges go from T_i to T_{i+1}, T_i must have accessed x_i before T_{i+1}.

-

For T2 to have acquired its locks—in particular, x1.lock—

T1 must have previously released x1.lock. Thus:

T1 acquires x1.lock

T1 releases x1.lock

T2 acquires x1.lock and x2.lock

T3 acquires x2.lock and x3.lock

…

Tk acquires x_k.lock and x_{k-1}.lock

T1 acquires x_k.lock -

Focusing just on the steps that involve T1:

T1 acquires x1.lock

T1 releases x1.lock

T1 acquires x_k.lock -

T1 violates 2PL; it acquires a lock after releasing a lock

-

Therefore, cyclic conflict graph => 2PL was violated.

Alternatively, 2PL => acyclic conflict graph

Week 9: Distributed Systems Part II

Lecture 17 Outline

Course Info

Instructor

Departments

As Taught In

Spring

2018

Level

Topics

Learning Resource Types

Instructor Insights

notes

Lecture Notes

grading

Projects with Examples

assignment

Written Assignments