In this section, Prof. Beinart describes how he inherited the course from Prof. Lynch, and how the course has developed over the years. He also describes how the course serves the class demographic at MIT.

A Legacy Left by Lynch

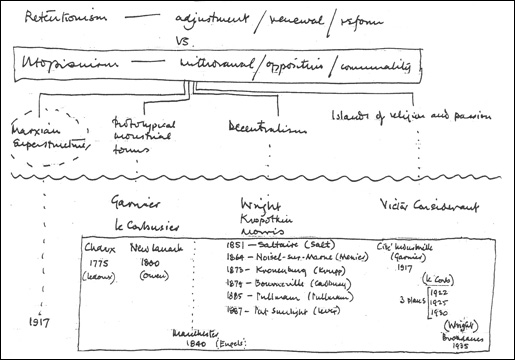

A timeline of Utopian models proposed in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that serve as the basis of discussion in several class lectures.

This course was first taught at MIT by Kevin Lynch for nearly two decades. In the late 1970’s, he felt that theory was no longer interesting to students. He thought that students had moved toward a much more applied understanding of the world, and he was disappointed about that. He stopped me one day, told me this, and I said, “You’re crazy! This is an important course.” He said, “Okay, I’ll make a deal with you. If you think that it is so important, why don’t you teach with me?”

We did alternate lectures, and I learned a lot from having to teach in front of him. We would discuss the course, and we were quite frank about what we said to each other. He was at a point where he was trying to develop a theory, an encompassing theory of city form of his own, which appeared in his book, Theory of Good City Form. In his version of the course, this unified theory was a primary focus.

When Lynch retired, I was left with having to construct my own version of this course. In the beginning I didn’t know what to do; I am still not sure I know what I’m doing, but I have enough courage to do it anyway.

I stopped focusing on attempting to construct a unified theory, and was interested in presenting a much wider spread of information and introducing new ideas alongside new historical information. The amount of time that I now spend on the nineteenth century is much greater. For example, in Lynch’s classes, we hardly ever spoke about Manchester or Friedrich Engels’s time.

Expectations in the Course

This course is structured around lectures in the traditional, classic sense of a lecture. There is not much discussion in class because there is so much material. Though this course is not a seminar, I let the students know that if they want to ask me a question, they should interrupt me at any point in time—and people do. And though the course is not dependent on the immediate feedback of students, I always begin the class by asking students if they have any questions about the previous class.

The course is an attempt to create a community of thought. If I had to reteach this course or reorganize it, I probably would reduce the amount of material and throw away one-third of it in order to leave much more time to talk and get students’ reactions. In this particular course, we have a high percentage of foreign students. They come from universities in which discussion is not part of their intellectual culture. Some women from the Middle East have told me, “I have never asked a professor a question, ever.”

What is also interesting, but difficult, is that the class has a wide variety of students. I have had undergraduates from Wellesley, PhD students, and visiting scholars in addition to the MArch, SMArchS, and urban studies students. They all come from different backgrounds including social science, engineering, and a variety of others. Because this is an advanced course, I tend to ignore what the audience is made of; otherwise, I would have to stop every time I mention a name such as Walter Gropius. An architect would know who Walter Gropius is, but somebody from economics would not. I don’t have the time to explain everything, and so some students will have to do some more didactic work on their own to supplement their knowledge from class.

MIT is a wonderful place to teach. I am arrogant in that I think that this is the best course of its kind in the world; it should be. People here are used to excellence and demanding things, and they are used to inventing new ways of doing things. We have the advantage of places like MIT, as opposed to high schools or training schools, to employ devices of teaching that deal with big questions that the brain has to put together on its own. You can’t spoon-feed people in an advanced course, but instead build on ideas to help bring to light new ones that they may not have discovered yet.