« Previous

Session Overview

How do we become who we are? This discussion session complements the prior lecture session Personality.

Discussion

Why do we behave as we do? How is it based on our predisposition to handle certain situations in certain ways? These are such interesting topics, and they’re really at the core of psychology. Why do people do what they do? Some people like to talk to other people, and some people like to sit at home, and some people like to try new things – and it just doesn’t seem like the kind of thing that the early approaches to psychology, like behaviorism, or even cognitive science today, can explain very easily. And in some ways that’s too bad, because it would be nice to be able to tell you which genes make you an extrovert, or what the difference in amygdala response is among people of different personality types, but it just isn’t known why there is such variability. But that seems like exactly what we want to know: why people behave differently in different situations. So to me, this personality topic is exciting.

› Students in this class were interested in topics like these

I found it interesting that genes seem to play such a big part in personality, since I always thought it had more to do with the environment you were raised in and the people who raised you. But I’m troubled by what the implications are for eugenics, the idea that breeding should be controlled in order to improve the genes of a population.

Eugenics was a big deal in the United States, even before it became politicized in Europe as very racist. Of course in the modern era, with our understanding of genetics and reproductive technologies, it’s still an important ethical question. Even though we say personality is heritable, we should distinguish between behavioral genetics and modern genetics. Behavioral genetics is when we try to determine the proportion of variance in the population is explained by some kind of family relationship. That gives us statistics about heritability. But genetics, in our modern understanding, calls to mind genes and splicing and testing it out on different groups of mice with different genes knocked out. That part of genetics and personality is just not known. It’s not clear that a conscientious mom and a conscientious dad will have a conscientious baby.

Have these theories of breeding for personality traits been tested in animals?

There is some work on that. The research I’m familiar with has to do with domestication. In Russia, during the Cold War, they were interested in the genes that made animals domestic, because domestic animals share a lot of traits with each other. They have spotted fur, floppy ears and floppy tails, and they tend to approach people. So they started with a group of wild foxes and bred the ones that were least unfriendly to people for several generations. And they got foxes that seemed to be, from a human perspective, agreeable and open to being held and petted. And as they did this, the other traits, like floppy ears and floppy tails, came along too. So there is some reason to think that there are genes that code for proteins that are related to personality traits.

How have they concluded that environment has very little impact on personality?

Personality research is dominated by self-report along the lines of, “How do I feel I react in certain situations?” The reason for this is that it’s the easiest and most efficient way to do an assessment. You could also follow them around all day and observe their behavior, or you could bring in their friends and family and interview them.

What’s more accurate, self-report or friends’ accounts of your personality?

“Accuracy” is an interesting question. But we can talk about reliability, or whether these reports tend to agree with each other. As it turns out, people tend to be very good about reporting their personality. There’s a good amount of correspondence between self-reported personality, what friends say, and what a naïve observer sees. That’s why psychologists prefer the self-report, since they don’t have to follow people around or pay lots of extra people to take surveys. Of course, we can imagine that there are certain areas of our personalities that we are not particularly proud of and tend not to report.

So, let’s a talk about a rigid definition of personality. A personality is a set of behavioral, emotional, and cognitive tendencies that people display over time and across situations that distinguish individuals from each other.

We can think about two components of personality: personality traits and personality dimensions. Personality traits are relatively consistent characteristics exhibited in different situations, such as whether you like to meet new people or whether you take careful notes. Personality dimensions are combinations of these traits that tend to go together. For example, people who like to meet new people tend to like to go to big parties. When you have enough that pattern together consistently, you have a personality dimension. The Big Five is an example of a model of personality dimensions. You answers questions about your traits and what emerges is your position on a continuum for each dimension: neuroticism, agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, and openness. There has also been a lot of speculation as to how each of these may be adaptive, or helpful for our survival.

As far as personality theories go, throughout the history of psychology, there has been a lot of interest in Freud’s theories. I feel that we should recognize their importance in the field, but know that they are a type of armchair philosophy that isn’t empirically testable.

So, how do we do personality psychology today? The empirical basis of it includes inventories such as the Big Five, projective tests, observations, and interviews. Inventories are big questionnaires that you fill out about how you act in certain situations. In projective tests someone interprets your personality based on your response to a given stimulus. The two big ones are the Rorschach and the Thematic Apperception Test. Let’s try some of these.

Demonstration

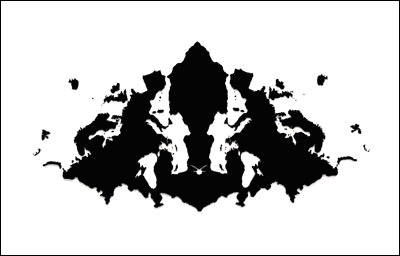

This is the Rorschach, or the ink blot test, that everyone is familiar with. Your job is to interpret this figure so that a psychoanalyst can tell you what’s wrong with you. So, is there a brave soul who wants to describe what they see?

© Unknown. All rights reserved. This content is excluded from our Creative Commons license. For more information, see http://ocw.mit.edu/fairuse.

› Students in this class saw

The face of a mouse or of Andre the Giant; a person extending his arms and singing.

Anyway, some of the other teaching assistants and I see something disturbing in this picture. You’re welcome to look for it. It’s open to your interpretation and your personality. In other words, those of you who are laughing and blushing clearly see it, and those of you who don’t are clearly upstanding citizens. How about this one?

© Unknown. All rights reserved. This content is excluded from our Creative Commons license. For more information, see http://ocw.mit.edu/fairuse.

› Students in this class saw

Elves wearing big hats; alien scientists; people getting water from a well.

Sure, lots of people will see lot of different things in here, because they’re just random patterns. It’s like looking for shapes in the clouds: ah, a cat; ah, a palm tree; ah, an angry man with a chainsaw. But the question is whether it says something about your personality. Do people with different personalities see different things? One problem with this test is there’s no objective set of measurements – no list of what certain responses to certain pictures might indicate about one’s personality.

Demonstration

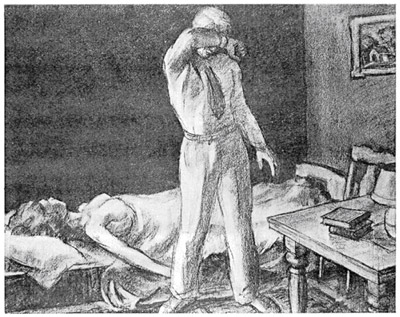

Let’s try the Thematic Apperception Test. You’re going to see a drawing of a scene, and the point of the test is not to describe it, but to tell the story: what happened before, what’s happening now, how do they feel, what’s going to happen next. Let’s look at one, and a brave soul can tell me the story:

© Unknown. Image appears in the Thematic Appreciation Test, developed by Henry A. Murray and Christiana D. Morgan. All rights reserved. This content is excluded from our Creative Commons license. For more information, see http://ocw.mit.edu/fairuse.

What, no response? No one wants to share a story? Well, I can share a story that I heard from a student in another discussion section. He said, “There’s a man who’s very dedicated to his work. He’s been working all night on really important things, and he worked so hard that he just fell asleep in his clothes. And then somebody opened the door and light flooded into the room and woke up him up. It was so bright that he shielded his eyes. Now he’s going to put his suit jacket back on and go back to work because he’s such a dedicated worker.”

So, you’re all laughing. When I heard that story, I said, “Wow, MIT has really ruined you.” There’s a lot more going on here than a man working. Well, it turns out that this student was sitting behind someone really tall and actually hadn’t seen that other part of the picture. But I really wanted to read something into it and say something about his personality (conscientious to the extreme!) because he hadn’t mentioned part of the picture. Of course, the interpretation of your story is totally up to the psychiatrist.

Discussion

From class, it almost seemed like there were no environmental influences on personality. I will present to you a few pieces of evidence that suggest that there is an influence, even if we’re not sure what the mechanism is. The first is birth order. People who are born in certain places tend to pattern in a certain way along the various personality dimensions. First-born children tend to be more responsible, more ambitious, and more assertive. Children who are born in the middle tend to be more rebellious, more impulsive, less conscientious, and more interested in doing their own thing. The youngest are often more agreeable, warmer, more idealistic, and more sociable. For those of you with siblings, is this consistent with your experience?

This is not something that psychologists have just figured out. It’s common in our literature and our culture, and cross-culturally, too. What do you think the explanation is for this? What might be the effect of a large age gap between siblings?

Across cultures, we also find differences in reported personality. When we get to social psychology we’ll talk more about this idea of collectivist and individualist cultures, but we’ll talk briefly about it here. Collectivist cultures emphasize the rights and responsibilities of the group over those of the individual, and this is typically how East Asian cultures are described. Individualist cultures, on the other hand, emphasize the rights and responsibilities of the individual, which is huge in the United States, as you can see in the idea of the “self-made man” and read in the Declaration of Independence (“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness”). So, as it turns out, people from collectivist cultures tend to be less assertive when meeting new people. Is this consistent from what you might expect, based on these cultural differences? Does it seem like an environmental effect on personality?

Here’s another interesting fact: a personality inventory was given all across the world. The countries that scored lowest on conscientiousness – those who rated themselves lowest, who said they were least likely to work hard – were China, Japan, and Korea. Hmm. So let’s think for a second about our stereotypes of people who come from these backgrounds. Would you say that your Chinese, Japanese, and Korean peers are the least conscientious, the least diligent people you know? That they’re always blowing off their work? Like, not at all! Why do you think they might rate themselves much lower?

› Sample answer

There may be a belief in the culture that you shouldn’t think too highly of yourself. (But interestingly, these cultures don’t differ in how they rate themselves on agreeableness, extroversion, or neuroticism – just on conscientiousness.) There also may be higher expectations of conscientiousness in those cultures.

Let me give you one more piece of evidence about self-reported conscientiousness, and we’ll see if we can figure this out. So, at West Point, the prestigious military academy, where you’re trained to be an officer, they give a personality inventory every year. Entering cadets rate themselves very highly on conscientiousness, but the longer they spend at West Point, the lower they rate themselves on conscientiousness. What do you think is going on here?

› Sample answer

As the cadets transition from high school to West Point, it’s as if the standards change. Suddenly they’re surrounded by people who are really on the ball, and suddenly they don’t seem so conscientious anymore.

To return to question about East Asian cultures, do you think it’s an example of the same phenomenon? Remember, your personality is what distinguishes you from other people. Even if you are, in fact, very conscientious, in comparison to highly-conscientious people, you may rate yourself fairly low.

« Previous