While Newton’s method is fast, it has a big downside: you need to know the derivative of \(f\) in order to use it. In many “real-life” applications, this can be a show-stopper as the functional form of the derivative is not known. A natural way to resolve this would be to estimate the derivative using

\begin{equation} \label{eq:dervative:estimate} f’(x)\approx\frac{f(x+\epsilon)-f(x)}{\epsilon} \end{equation}

for \(\epsilon\ll1\). The secant method uses the previous iteration to do something similar. It approximates the derivative using the previous approximation. As a result it converges a little slower (than Newton’s method) to the solution:

\begin{equation} \label{eq:3} x_{n+1}=x_n-f(x_n) \frac{x_n-x_{n-1}}{f(x_n)-f(x_{n-1})}. \end{equation}

Since we need to remember both the current approximation and the previous one, we can no longer have such a simple code as that for Newton’s method. At this point you are probably asking yourself why we are not saving our code into a file, and it is exactly what we will now learn how to do.

Coding in a File

Instead of writing all your commands at the command prompt, you can type a list of commands in a file, save it and then have MATLAB® “execute” all of the commands as if you had typed them into the command prompt. This is useful when you have more than very few lines to write because inevitably you are bound to make a small mistake every time you write more than 5 lines of code. By putting the commands in a file you can correct your mistakes without introducing new ones (hopefully). It also makes it possible to “debug” your code, something we will learn later.

For guided practice and further exploration of how to debug, watch Video Lecture 6: Debugging.

MATLAB files have names that end with .m, and the name itself must comprise only letters and numbers with no spaces. The first character must be a letter, not a number. Open a new file by clicking on the white new-file icon in the top left of the window, or select from the menu File\(\rightarrow\)New\(\rightarrow\)Script. Copy the Newton method code for \(\tanh(x)=x/3\) into it. Save it and give it a name (NewtonTanh.m for example). Now on the command prompt you “run” the file by typing the name (without the .m) and pressing Enter .

A few points to look out for:

- You can store your files wherever you want, but they have to be in MATLAB’s “search path” (or in the current directory). To add the directory you want to the path select File\(\rightarrow\)Set path… select “Add Folder”, select the folder you want, click “OK” then “Save”. To check if your file is in the path you can type

which NewtonTanhand the result should be the path to your file. - If you choose a file-name that is already the name of a MATLAB command, you will effectively “hide’’ that command as MATLAB will use your file instead. Thus, before using a nice name like

sum, orfind, orexp, check, usewhichto see if it already defined. - The same warning (as the previous item) applies to variable names, a variable will “hide” any file or command with the same name.

- If you get strange errors when you try to run your file, make sure that there are no spaces or other non-letters in your filename, and that the file is in the path.

- Remember that after you make changes to your file, you need to save it so that MATLAB will be aware of the changes you made.

For guided practice and further exploration of how to use MATLAB files, watch Video Lecture 3: Using Files.

Exercise 7. Save the file as SecantTanh.m and modify the code so that it implements the Secant Method. You should increase the number of iterations because the Secant Method doesn’t converge as quickly as Newton’s method.

Notice that here it is not enough to use x like in the Newton’s method, since you also need to remember the previous approximation \(x_{n-1}\). Hint: Use another variable (perhaps called PrevX).

Convergence

Different root-finding algorithms are compared by the speed at which the approximate solution converges (i.e., gets closer) to the true solution. An iterative method \(x_{n+1}=g(x_n)\) is defined as having \(p-\)th order convergence if for a sequence \(x_n\) where \(\lim_{n\rightarrow\infty}x_n=\alpha\) exists then

\begin{equation} \label{eq:convergence:order} \lim_{n\rightarrow\infty}\frac{|{x_{n+1}-\alpha}|}{|{x_n-\alpha}|^p} = L \ne 0. \end{equation}

Newton’s method has (generally) second-order convergence, so in Eq. (3) we would have \(p=2\), but it converges so quickly that it can be difficult to see the convergence (there are not enough terms in the sequence). The secant method has a order of convergence between 1 and 2. To discover it we need to modify the code so that it remembers all the approximations.

The following code, is Newton’s method but it remembers all the iterations in the list x. We use x(1) for \(x_1\) and similarly x(n) for \(x_n\):

x(1)=2; % This is our first guess, put into the first element of x

for n=1:5 % we will iterate 5 times using n to indicate the current

% valid approximation

x(n+1)=x(n)-(tanh(x(n))-x(n)/3)/(sech(x(n))^2-1/3); %here we

% calculate the next approximation and

% put the result into the next position

% in x.

end

x % sole purpose of this line is to show the values in x.

The semicolon (;) at the end of line 4 tells MATLAB not to display the value of x after the assignment (also in line 1. Without the lonely x on line 9 the code would calculate x, but not show us anything.

After running this code, x holds the 6 approximations (including our initial guess) with the last one being the most accurate approximation we have:

x =

2.0000 3.1320 2.9853 2.9847 2.9847 2.9847

Notice that there is a small but non-zero distance between x(5) and x(6):

>> x(6)-x(5)

ans =

4.4409e-16

This distance is as small as we can hope it to be in this case.

We can try to verify that we have second order convergence by calculating the sequence defined in Eq. (3). To do that we need to learn more about different options for accessing the elements of a list like \(x\). We have already seen how to access a specific element; for example to access the 3rd element we write x(3). MATLAB can access a sublist by giving it a list of indexes instead of a single number:

>> x([1 2 3])

ans =

2.0000 3.1320 2.9853

We can use the colon notation here too:

x(2:4)

ans =

3.1320 2.9853 2.9847

Another thing we can do is perform element-wise operations on all the items in the list at once. In the lines of code below, the commands preceding the plot command are executed to help you understand how the plot is generated:

>> x(1:3).^2

ans =

4.0000 9.8095 8.9118

>> x(1:3)*2

ans =

4.0000 6.2640 5.9705

>> x(1:3)-x(6)

ans =

-0.9847 0.1473 0.0006

>> x(2:4)./(x(1:3).^2)

ans =

0.4002 0.0018 0.0387

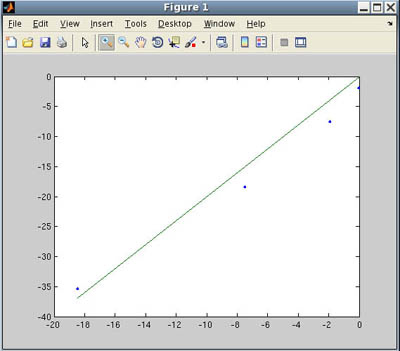

>> plot(log(abs(x(1:end-2)-x(end))),log(abs(x(2:end-1)-x(end))),'.'))

The last line makes the following plot (except for the green line, which is \(y=2x\)):

MATLAB can calculate roots through Newton’s method, and verification of convergence is graphed.

The main point here is that the points are more or less on the line y=2x, which makes sense:

Taking the logarithm of the sequence in (3) leads to

\begin{equation} \label{eq:convergence:plots} \log|{x_{n+1}-\alpha}| \approx \log L + p\log|{x_{n}-\alpha}| \end{equation}

for \(n\gg1\), which means that the points \((\log|{x_{n}-\alpha}|, \log|{x_{n+1}-\alpha}|)\) will converge to a line with slope \(p\).

The periods in front of *, /, and ^ are needed (as in the code above) when the operation can have a linear algebra connotation, but what is requested is an element-by-element operation. Since matrices can be multiplied and divided by each other in a way that is not element-by-element, we use the point-wise version of them when we are not interested in the linear algebra operation.

Exercise 8. Internalize the differences between the point-wise and regular versions of the operators by examining the results of the following expressions that use the variables A=[1 2; 3 4], B=[1 0; 0 2], and C=[3;4]. Note: some commands may result in an error message. Understand what the error is and why it was given.

A*Bvs.A.*Bvs.B.*Avs.B*A2*Avs.2.*AA^2vs.A*Avs.A.*Avs.A.^2vs.2.^Avs.A^Avs.2^A. The last one here might be difficult to understand…it is matrix exponentiation.A/Bvs.A\Bvs.A./Bvs.A.\BA*Cvs.A*C'vs.C*Avs.C'*AA\Cvs.A\C'vs.C/Avs.C'/A

Homework 2. Modify your secant method code so that it remembers the iterations (perhaps save it in a new file?). Now plot the points that, according to (4) should be on a line with slope \(p\). What is \(p\)?