Link to Yuliya Klochan’s Page on Tumblr

Contents

- Day 1 Gödel’s Theorem Video Pitch

- Day 2 Math Woman Saves the World Script

- Day 3 Trailer

- Day 4 Storyboard

- Day 5 Fractals Video Script Draft 2

- Day 6 Fractals! Script Revisited

- Day 7 Script

- Day 8 Fractals! Shot List

- Fractals! Rough Cut

- Final Project

- Science Out Loud

Day 1 Gödel’s Theorem Video Pitch

This video is courtesy of Yuliya Klochan on YouTube and is provided under our Creative Commons license.

The beginning of an odd mathematical journey that asks (but cannot always answer) questions like, “Is math true?” or “Could The Matrix scenario happen to us?”

Day 2 Math Woman Saves the World (the Script)

Note: This seems, at this point, an odd amalgamation of various mathematical ideas. A read-through takes just under 5 minutes, but I will most likely filter a lot of the material. I just wanted to grasp the character for now. Also, phrases in brackets [] are optional and italicized ones are filming directions.

(in a thunderous voice over an “interesting” theatrical background)

Introducing your new favorite superhero…

(thunder, Math Woman revealed standing tall in her superhero suit)

Math Woman!!!

Now, you’ve heard of Batman, Iron Man, Hulk… (show images of these characters)

But have you heard of Math Woman, the glorious offspring of Mathematics, the Queen of All Sciences? Math Woman is the Superhero Princess that always saves the world.

Here’s her story.

(The following involves acting, changing clothing with often goofy results, and using props / people; in the interest of the reader’s eyes, I will omit the description of most scenes)

Every morning Math Woman gets dressed in a perfectly matched outfit, always aware of the latest fashion trends ahead of everyone else. She smiles a golden ratio smile. [Scientists calculated it to be perfection.]

Sometimes Math Woman confuses a cup with a donut at breakfast, a mistake many of her followers, mathematicians, may make [though don’t tell them that]. But she always makes the perfect half-inch toasted bread [coated with exactly 0.4 grams of butter per square inch.] (show delectable toast here)

On days when the world is safe, Math Woman then relaxes at home. Once, she solved an important math problem and earned a million dollars. She will never have to work again.

Instead, Math Woman may create the world’s wackiest art (fractals) and find that it can help cure cancer. She may compose the next latest music hit or the world’s ugliest tune [so ugly it hurts! (play if possible)]; play a game to predict a war, solve a crime, find a terrorist’s bomb…

At snack time, Math Woman gobbles up an infinite number of chocolate pieces: First a half, then a quarter, an eighth…. Ask your math teacher how she still stays in shape after that!

Still seems like a pretty regular being? Well, here are some Superbly Superb Superpowers Math Woman possesses.

She can make two bowling balls out of one with no extra materials, or talk to anyone in the world with the universal language of Math. (show cool math formula images)

How can she do that? Well, Math Woman sees patterns, shapes, and numbers in everything and everyone. This allows her to do incredible stuff, like predicting the future, or even travelling to infinity and beyond. (show Buzz Lightyear image if copyright laws allow it)

And, so, if her powers predict a disaster, Math Woman immediately flies to the rescue.

A typhoon happening, you say? Math Woman is way ahead of you.

(different voice, childlike)

Does Math Woman ever get in trouble?

(back to normal)

Well, of course. No Superhero Princess is perfect.

(change of scene for a more dramatic fantasy setting)

One time, for example, giant robots attacked the Earth. (show footage from some film showing machines attacking, if possible)

Everyone was terrified. The robots talked and behaved just like us, and it seemed that they were even stronger…

Math Woman had no idea what to do. She was smart, but could she defeat the awful machines?

And then, Queen Mathematics stepped in. She sent a message to young mathematician Kurt Godel, who immediately set out to help Math Woman on her quest. He said to her,

(male voice, background could be an image of Godel)

“Machines can never be as smart as humans. We are infinitely more powerful than they are with our minds. Mathematics proved it, so it must be true. Don’t give up, Math Woman!”

(back to normal)

And Math Woman didn’t. The problem before her was a challenge. But she took her time and persevered.

Naturally, Math Woman won.

Never again would the evil robots threaten humanity. And if they did, ha, we would always win anyway.

Do you know how?

Math Woman applies what you learn at school to save the world. And if you practice solving those puzzling math problems, you can soon become just like her. After all, Math Woman knows that there are millions other heroes out there. You can ask Queen Mathematics herself.

So, explore what Math Woman has to say. Don’t give up when the difficult villains come. Then, you, too, can join Math Woman on an infinite pursuit of adventure.

(back to original background, dramatic final voice over)

Save the world with math. No superpowers required.

The End

Day 3 Trailer: Fractals!

This video is courtesy of Yuliya Klochan on YouTube and is provided under our Creative Commons license.

Day 4 Storyboard

Day 5 Script: Fractals Video Script (Draft 2)

Pitch

Repeating patterns called fractals are present in every facet of our existence, and are indispensable in nature research, medicine, and technology. In that way, mathematics helps us explore and understand the world around us.

(Camera zooms into host standing by the Charles River, talking on a cell phone; when camera is close, the host acknowledges it)

What do a cellphone, a river, and a cancer cell have in common?

The answer is… (black screen with the word animated on it, framed with images) fractals.

(back to Charles River, host drawing repeating pattern with chalk while talking)

Fractals in mathematics are never-ending patterns.

(Change setting: Now in a room with a blank wall and computer; show animation of Sierpinski triangle while talking on screen)

Scientists can program these infinite patterns by repeating a simple mathematical process over and over. So, if you zoom in, you’ll see the same shape again and again and again… (show making sierpinski).

Similarly, a tree grows by repetitive branching. Just like our fractal, a tree extends its branches, one smaller than the other, but similar.

Of course, a tree can’t grow as far and precisely as a “truly mathematical” fractal, but parts of it show enough like properties that we can study nature in terms of fractals.

In fact, so many things in nature have these pattern properties (show snowflake and seashell, fill screen with others–fern, water spinning out of tap; somehow zoom in or show similar parts), it sometimes feels like the world itself is one giant fractal! (fill the screen with patterned shapes until it’s too much)

So Many Fractals!!! (head spin)

A bit overwhelming, right? Well, one way to explain this abundance of patterns is the fact that nature is just great at reusing efficient mechanisms.

Rivers of the planet flow like the “rivers of blood” in our bodies. Lightning bolts become electrifying rivers of the sky. And just look at this honey!

Here’s something even wackier: A brain fractal shaped forest!

Whew, that’s enough fractals to make my fractal brain hurt.

Luckily, mathematicians have found a way to describe the wacky structures. They’ve accepted that clouds are not spheres and bark is not smooth… But, with fractal geometry, we can mathematically explore them!

In the 1970’s, a mathematician named Benoit Mandelbrot was hired to investigate noise in telephone lines. Now, Mandelbrot loved connecting images with numbers, so he immediately looked at the noise in terms of the shapes it created. And he came up with this: (Show Mandelbrot set and talk over it)

At first, the image didn’t look too special. In fact, it kinda resembled a turtle with a giant head (show turtle).

It wasn’t until nighttime that Mandelbrot looked closer. He zoomed in once, and found a smaller turtle latched on to the original one. And an even smaller turtle on that one. Mandelbrot kept zooming and zooming and the turtles kept shrinking and shrinking, but they were still all the same shape!

Mandelbrot was convinced he’d seen a nightmare! But when the shape remained on the screen the next day, Mandelbrot knew he was onto something huge. A simple equation, applied repeatedly, carried incredible properties.

What if, thought he, you could create such expressions for other natural phenomena?

And that’s exactly what mathematicians do today. Fractal geometry allows them to model, say, mountain ranges (animate from fractal triangles), and then use the models to study earthquakes or create realistic special effects for our favorite movies (Star Wars battle / death scene; pause, then show me looking disturbed).

In healthier news, fractals may also help doctors diagnose cancer faster and more accurately. They can study the edges of various cells in our bodies using fractal geometry. Here, the cell on the right is more jagged and repeating than that on the left, which means it’s the more aggressive, faster-growing cancer cell. This way of discovering cancer can be about 10 times more effective than the current methods!

So that’s how cancer cells and rivers relate. But what about cell phones? They aren’t really a part of nature.

Well, in the 90’s, a radio astronomer by the name of Nathan Cohen was having troubles with his landlord. The man wouldn’t let him put a radio antenna on the roof! So, Cohen decided to make a more compact, fractal radio antenna instead (Koch)

The landlord didn’t notice it, and it worked better than the ones before!

Working further, Cohen designed a new version, this time using a shape called “the Menger Sponge” (voiceover over animation of traveling through the Menger Sponge). The fractal’s infinite “sponginess” allowed the antennae to receive multiple different signals.

(soapy sponge used as prop; maybe host is in shower?)

The Menger Sponge is not really the sponge you’d be scrubbing your back with, but you can still think of it like that. Imagine both water and soap getting through your sponge’s holes, except the water is Wi Fi and the soap is, say, Bluetooth. Without Cohen’s “sponge,” your cell phone would have to look something like a giraffe to receive both those signals (illustrate: Phone with antennas glued on for those two signals). Not quite as handy, is it?

(closing statement delivered at original Charles River location)

Fractals are already very common, yet we are still searching for more applications, asking questions, building new patterns and exploring nature’s best. Here at MIT (move camera from host and Charles river to MIT dome right across) and everywhere in the world.

Look around you. What beautiful patterns do you see?

The End

Day 6 Fractals! Script Revisited

What do snowflakes and cell phones have in common?

Snowflakes have intricate detail no matter how closely you look. In mathematics, such shapes are called fractals.

Fractals are never-ending patterns that on any scale, on any level of zoom, look roughly the same. Computer scientists can program these infinite patterns by repeating an often simple mathematical process over and over.

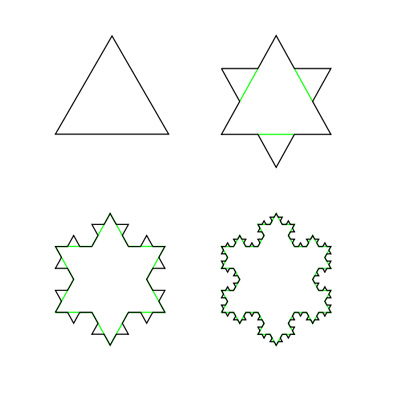

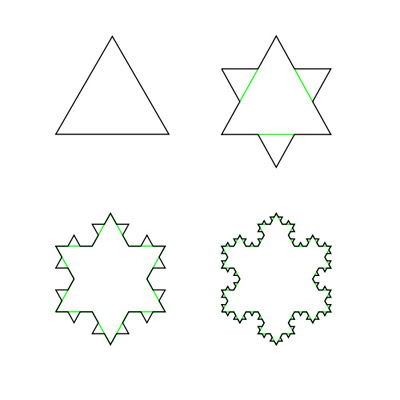

To model a snowflake, for example, start by drawing an equilateral triangle. Divide each side into three equal parts and build another equilateral triangle on top of each side.

Take out the middle, and repeat the process, this time with 1, 2, 3, 4 times 3, which are 12 sides. Eventually, the shape will look something like this:

This curve is called in mathematics a Koch Snowflake. It is a fractal because, if you zoom in, you’ll get this same pattern (show pattern) again and again.

The Koch fractal is useful not only for modeling snowflakes.

In 1990’s, a radio astronomer named Nathan Cohen used the Koch snowflake to revolutionize wireless communications.

At the time, Cohen was having troubles with his landlord. The man wouldn’t let him put a radio antenna on the roof! So, Cohen decided to make a more compact, fractal radio antenna instead (show wire bent as Koch snowflake.)

The landlord didn’t notice it, and it worked better than the ones before!

Working further, Cohen designed a new version, this time using a fractal called “the Menger Sponge” (build a tangible model of the Sponge, and show it). The fractal’s infinite “sponginess” allowed the antennae to let through multiple different signals.

(soapy sponge used as prop; maybe host is in shower?)

The Menger Sponge is not really the sponge you’d be scrubbing your back with, but you can still think of it kind of like that. Imagine both water and soap getting through your sponge’s holes, except the water is Wi Fi and the soap is, say, Bluetooth.

The fractal shape allows the antenna to operate well at many different frequencies simultaneously. Before Cohen’s invention, antennas had to be “cut” for one necessary frequency. That was the only frequency they could operate at.

So, without Cohen’s “sponge,” your cell phone would have to look something like a hedgehog to receive different signals, including the radio signal that allows you to hear your friends when they call (illustrate: Phone with several antennas glued on). As Cohen later proved, only fractal shapes could work with such a wide range of frequencies.

Today, millions of wireless communication devices, such as laptops and barcode scanners, also use Cohen’s fractal antenna.

Cohen’s genius invention, however, was not the first application of fractals in the world. Turns out, nature has been doing it the whole time!

Natural selection has allowed it to create the most efficient systems and organisms, most of which (if not all) evolved to a fractal shape.

The spiral fractal, for example, is present in seashells, broccoli, and hurricanes.

So, many natural systems previously thought off-limits to mathematicians were suddenly explained in terms of fractals. The fractal tree for example, is relatively easy to program, and allows mathematicians to study anything from river systems to blood vessels and lightning bolts.

Thus, fractals allow us to learn nature’s best practices, and then apply them to solve real world problems. Much like Cohen’s antenna revolutionized telecommunications, other fractal research is changing fields of medicine, weather prediction, and many more. Here at MIT (move camera from host and Charles river to MIT dome right across) and everywhere in the world.

Look around you. What beautiful patterns do you see?

Day 7 Script (Fractals!)

What do snowflakes and cell phones have in common?

Well, let me start by drawing a snowflake.

First, I’d draw an equilateral triangle, divide each side into three equal parts, and build another equilateral triangle on top of each side (this “demo” can be done on a blackboard or whiteboard).

Then take out the middle, and repeat the process, this time with 1, 2, 3, 4 times 3, which are 12 sides. Eventually, the shape will look something like this:

This curve is called in mathematics a Koch Snowflake. If I repeated the process again and again, and looked anywhere, I would see this same pattern: (Show)

Such never-ending patterns that on any scale, on any level of zoom, look roughly the same are called fractals. Computer scientists can program these infinite patterns by repeating an often simple mathematical process over and over.

In 1990’s, a radio astronomer named Nathan Cohen used the Koch snowflake to revolutionize wireless communications.

At the time, Cohen was having troubles with his landlord. The man wouldn’t let him put a radio antenna on the roof! So, Cohen decided to make a more compact, fractal radio antenna instead (show wire bent as Koch snowflake.) The landlord didn’t notice it.

And it worked better than the ones before!

Working further, Cohen designed a new version, this time using a fractal called “the Menger Sponge” (build a tangible model of the Sponge, and show it).

(soapy sponge used as prop; maybe host is in shower?)

The Menger Sponge is not really the sponge you’d be scrubbing your back with, but you can still think of it kind of like that. Imagine both water and soap getting through your sponge’s holes, except the water is Wi Fi and the soap is, say, Bluetooth.

The fractal’s infinite “sponginess” allows the antenna to operate well at many different frequencies simultaneously. Before Cohen’s invention, antennas had to be “cut” for one necessary frequency. That was the only frequency they could operate at.

So, without Cohen’s “sponge,” your cell phone would have to look something like a hedgehog to receive different signals, including the radio signal that allows you to hear your friends when they call (illustrate: Phone with several antennas glued on and labels).

Cohen later proved that only fractal shapes could work with such a wide range of frequencies. Today, millions of wireless communication devices, such as laptops and barcode scanners, also use Cohen’s fractal antenna.

Cohen’s genius invention, however, was not the first application of fractals in the world. Nature has been doing it the whole time, and not just with snowflakes!

Natural selection favors the most efficient systems and organisms, often of a fractal shape.

The spiral fractal, for example, is present in seashells, broccoli, and hurricanes.

So, many natural systems previously thought off-limits to mathematicians can now be explained in terms of fractals. The fractal tree for example, is relatively easy to program, and allows mathematicians to study anything from river systems to blood vessels and lightning bolts.

Thus, fractals allow us to learn nature’s best practices, and then apply them to solve real world problems. Much like Cohen’s antenna revolutionized telecommunications, other fractal research is changing fields of medicine, weather prediction, and many more. Here at MIT (move camera from host and Charles river to MIT dome right across) and everywhere in the world.

Look around you. What beautiful patterns do you see?

Day 8 Fractals! Shot List

Clothing and Props

- Stata: Dark black / blue clothing to contrast murals; Props: Chalk, tissue, cell phone

- Outdoors: Light blue winter jacket, black pants and gloves

- EC Shower: Flip flops, I <3 MIT T shirt, black sports pants; Props: Sponge, soap, cup, towel, phone (anything glued on?)

- Office / Indoor Locations: Blue dress; Props: Laptop, bent wire (string?)

Locations

Stata Center (3 pm, January 14)

- By Pool Mural (Introduction): “What do snowflakes and cell phones have in common? Well, let me start by drawing a snowflake.”

- Balcony of Amphitheatre (Alternative Intro): Same text

- Blackboard (show demo of drawing the first iteration of Koch, then zoom to pre-drawn image of Koch Snowflake and its repeating pattern): “First, I’d draw an equilateral triangle, divide each side into three equal parts, and build another equilateral triangle on top of each side. Then take out the middle, and repeat the process, this time with 1, 2, 3, 4 times 3, which are 12 sides. Eventually, the shape will look something like this: (turn and gesture). This curve is called in mathematics a Koch Snowflake. If I repeated the process again and again, and looked anywhere, I would see this same pattern: (show).”

- By Mural of Broccoli: “Natural selection favors the most efficient systems and organisms, often of a fractal shape. The spiral fractal, for example, is present in seashells, broccoli, and hurricanes. The fractal tree is relatively easy to program, and allows mathematicians to study anything from river systems to blood vessels and lightning bolts. So many natural systems previously thought off-limits to mathematicians can now be explained in terms of fractals.”

- Balcony of Amphitheatre (Conclusion): “Thus, fractals allow us to learn nature’s best practices, and then apply them to solve real world problems. Much like Cohen’s antenna revolutionized telecommunications, other fractal research is changing fields of medicine, weather prediction, and many more. Here at MIT (move camera from host and Charles river to MIT dome right across) and everywhere in the world. Look around you. What beautiful patterns do you see?”

East Campus (12:30 pm, January 15)

- In Goodale Shower (with Wet Sponge): “The Menger Sponge is not really the sponge you’d be scrubbing your back with, but you can still think of it kind of like that. Imagine both water and soap getting through your sponge’s holes, except the water is Wi Fi and the soap is, say, Bluetooth.”

- Sit on Sink for Fractal Mirror Effect: “The fractal’s infinite “sponginess” allows the antenna to operate well at many different frequencies simultaneously. Before Cohen’s invention, antennas had to be “cut” for one necessary frequency. That was the only frequency they could operate at. So, without Cohen’s “sponge,” your cell phone would have to look something like a hedgehog to receive different signals, including the radio signal that allows you to hear your friends when they call (illustrate: Phone with several antennas glued on and labels).”

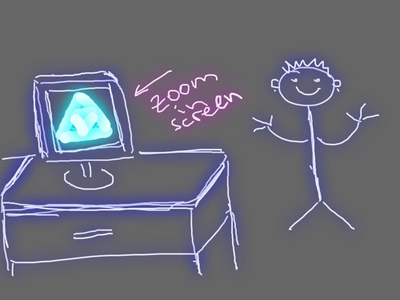

Office with Computer / Laptop (time TBD)

- (show graphic zoom of Koch Snowflake using XaOS software): “Such never-ending patterns that on any scale, on any level of zoom, look roughly the same are called fractals. Computer scientists can program these infinite patterns by repeating an often simple mathematical process over and over. In 1990’s, a radio astronomer named Nathan Cohen used the Koch snowflake to revolutionize wireless communications.”

- “Cohen later proved that only fractal shapes could work with such a wide range of frequencies. Today, millions of wireless communication devices, such as laptops and barcode scanners, also use Cohen’s fractal antenna. Cohen’s genius invention, however, was not the first application of fractals in the world. Nature has been doing it the whole time, and not just with snowflakes!”

Workspace / Lab (to be discussed)

- “At the time, Cohen was having troubles with his landlord. The man wouldn’t let him put a radio antenna on the roof! So, Cohen decided to make a more compact, fractal radio antenna instead (show wire bent as Koch snowflake.) The landlord didn’t notice it. And it worked better than the ones before! Working further, Cohen designed a new version, this time using a fractal called “the Menger Sponge” (build a tangible model of the Sponge, and show it).”

This video is courtesy of Yuliya Klochan on YouTube and is provided under our Creative Commons license.

Final Project

This video is courtesy of Yuliya Klochan on YouTube and is provided under our Creative Commons license.

Fractals!

Creative Commons: CC BY-NC-SA, MIT

Hosted By: Yuliya Klochan

Written By: Yuliya Klochan

Additional Scripting: Elizabeth Choe, Jaime Goldstein, Ceri Riley, George Zaidan, students of 20.219

See the full credits on the course Tumblr.

Science Out Loud

Yuliya’s video was professionally produced by Science Out Loud after this course finished.

This video is from MITK12Videos on YouTube and is provided under their Creative Commons license.